by Kiva Reardon, cross post from TIFF

Here are the positions people assume I hold when I meet them at film festivals: personal assistant, girlfriend, publicist. Sometimes, if I’m dressed well and have slept, I might get asked if I’m an actor. If I’m standing at the back of a room alone trying to take a breather, an event planner. I’ve sat down at dinner tables only to be passed over for an introduction. I’ve been in meetings where it’s assumed I’m there to take notes. Sometimes, I’ve been “lucky” enough to have male bosses or friends explain that I’m not a plus-one or an administrative appendage. While I’m grateful to those men who speak on my behalf, I also resent this reality of my professional life. It’s unnerving to see the click of recognition in a man’s eye after another man contextualizes me. It’s an eerie feeling of going from invisible to visible, and deeply upsetting to feel like you can’t control that powerful process yourself. I’ve always been taught that I can walk into any room and own it. But the reality is, my gender talks first in male-dominated circles — and I say that with the immense amount of privilege that comes with being a white, straight, economically privileged, cisgender person.

In the tech and business world, this off-the-cuff dismissal has become known as “unconscious bias”: the decisions all of us make within the first seconds of encountering another person based on race, gender, class, and ableism. Increasingly, this lens has been applied to the film world, especially when it comes to the representation behind the camera. Radheyan Simonpillai raised this point in the Canadian film context in a recent NOW Magazine cover story, where actor Tatiana Maslany said: “This shouldn’t even be a conversation any more. How is there still reticence toward change? We shouldn’t have to get angry because it shouldn’t be happening. I think people are really scared to shift systems. It is such a male system, and it works and makes money.” This year, many film festivals (including TIFF) and publications are trying to address why men seem to keep getting to be the ones yelling “action.”

But there’s another branch of the film world that’s also affected by representational disparity, and one that’s not discussed as frequently: film criticism. Earlier this year, San Diego State University published a study that found only 27 per cent of the “top critics” on Rotten Tomatoes were women. These stats had already been pointed to by Meryl Streep, who took the time to count the women on the review aggregator site, finding 760 male voices to 168 female ones. There have, of course, been famous female voices writing about film, from Judith Crist to Pauline Kael, to academics like bell hooks and Susan Sontag. But if we’re looking forward, then what San Diego U and Streep are pointing to is an ongoing failure across the film ecosystem. Today, getting women behind the camera is the main drive of so many conversations about inclusivity, overlooking that even when those women do get in the director’s chair, we still need voices to champion them. If the makeup of the film criticism world is largely like that of a fraternity, those unconscious biases are going to drive what stories on screen get written about — and how they’re written about, if at all.

This is all well and good to agree with on paper, but it really raises the question: what next? After many candid conversations with women in the field, three points kept coming up: dismantling the film canon, examining the media landscape, and questioning authority — especially when it comes to who is thought to have it and who even has access to gaining it.

Knowledge is power, but what’s often not addressed in film circles is what kind of knowledge is given power. This is essence the reign of the canon, which most academic film schools frame their curriculum around. It’s learning about the Lumière Brothers and not necessarily Alice Guy-Blaché; about the technical work of D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of the Nation in favour of discussing its role in inscribing racist imagery of black bodies; of having entire classes on Alfred Hitchcock and not Med Hondo or Agnès Varda. And as this canon has shaped criticism, it feels like the game has become about holding a certain deck of cards. Show up to the table with anything other than what’s been deemed an ace and good luck trying to take the hand.

This creates a gatekeeping effect, where it’s not just about expressing your opinion, but proving you merit having one to begin with. “Having my knowledge questioned constantly is different than having my writing questioned,” says Angelica Bastién, a Chicago-based writer and critic. It can be exhausting work for female critics, creating a double labour of not just defending your point but your seat at the table.

The role of the canon also shapes taste and what’s deemed worthy of critical thought. As Sophie Mayer, author of Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinemaand a regular reviewer for Sight & Sound, says, the domination of “the great canon of penis works” leads to “taste being held as being sacrosanct instead of [recognizing that it’s] being shaped by your personal experience and thought process.” As the playbook of film criticism is built to favour certain experiences and histories, those with expertise in other arenas are deemed “niche” or “small.” These are words that, as Mayer notes, become code for saying “female” or “coming from a marginalized experience.”

On a practical and pressing level, all of this means that contemporary conversations are often shaped through a predominantly white male lens. Simran Hans, a freelance writer based in the UK, points to how this played out earlier this year: “Think about all the people who watched Beyoncé’s Lemonade and decided that it was inspired by Terrence Malick without giving a second thought to Julie Dash or Kasi Lemmons or Zora Neale Hurston.” This isn’t to say female writers can’t or shouldn’t be considering the Malicks, Godards, and Truffauts that have shaped history along the way, but that we need a radical expansion of film knowledge. As Hans neatly said, “More diverse [perspectives] means less of a consensus means sharper criticism.”

The solution to expanding the canon could be “simply” to rewrite history, but in age of digital media, it increasingly feels like a battle of decibels. Nathalie Atkinson, a columnist at The Globe and Mail and freelance arts and culture writer, notes: “The context of criticism has changed so much [with the internet]. The free market is correcting itself, but instead of publications seeing it as an opportunity to innovate, they’re still hiring the loudest people.”

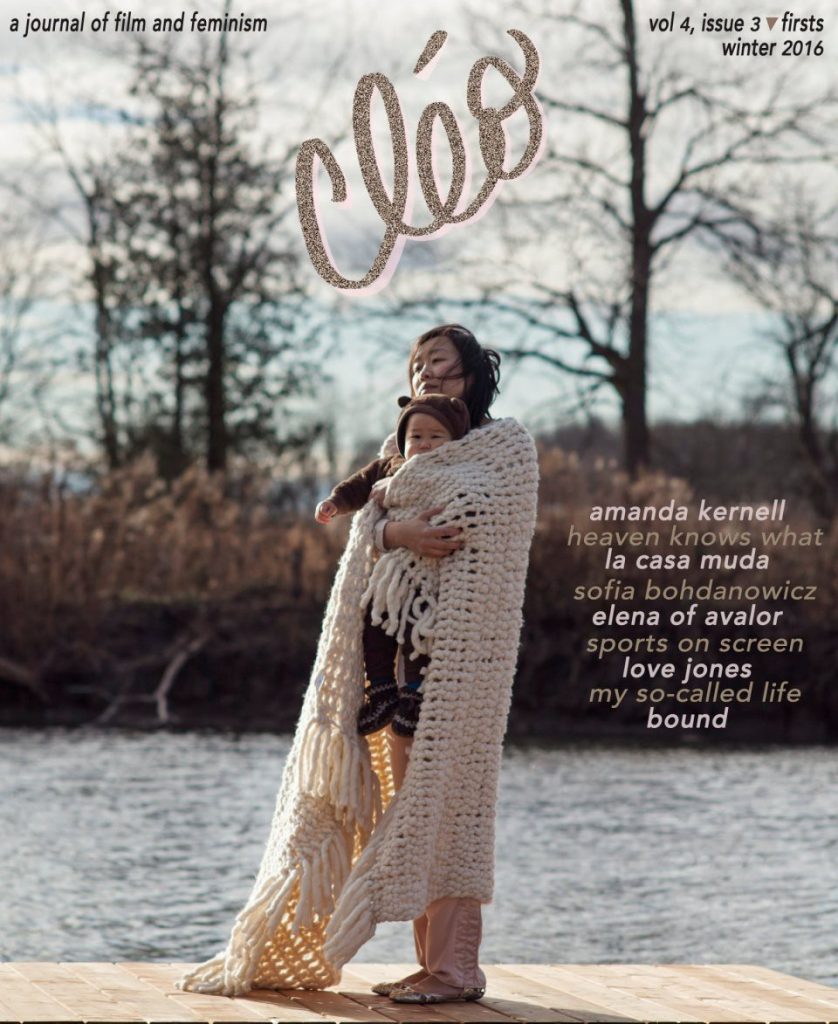

This reality was my motivation for starting cléo, a journal of film and feminism, with a group of women nearly four years ago. We wanted to create a space where new writers can get a foot in the door and then start working their way up the byline ladder. A space where writing about gender, race, and politics wouldn’t be seen as “marginal” or “not mainstream enough” and where writing about older or overlooked films was encouraged. 12 issues later, I believe we’ve made some progress. I firmly stand behind the quality of what we published, but I’m also not about to overlook the quantity: issue by issue, piece by piece, we’re intentionally chipping away at an industry that is very male and very white. But, admittedly, this work is slow and hardly lucrative. (While we’ve always fundraised to pay our writers, it wasn’t until this year that we could offer a small honorarium to our editorial staff, thanks to a grant from the Ontario Arts Council.) And as writing and editing full-time positions become scarce, the pressure on publications increases, meaning they are less and less likely to take risks on newer voices, or even work to cultivate new ones (once the defining work of a great editor). “When Varietyneeds to hire a new film critic, they need to justify it,” says Atkinson. So they’re more likely to bank on the voices that are “already given to being the boldest and loudest and steering the tenor of the conversation. Usually, men.” For all the talk of new media’s new possibilities — which of course do exist — larger platforms are still adopting the old-school pattern of punditry.

This results in a segmentation of “beats.” “I’m often assigned the ‘women’ or ‘POC’ beat,” says Hans to this point, “which isn’t necessarily a problem until say, the David Fincher interview I want to do gets given to a white dude.” This kind of editorial assigning strips away the possibility of women to be seen as generalists, as their perceived authority hinges on a projected idea of their lived experience and not necessarily their tastes. Plus, as Hans says: “It can be frustrating and emotionally draining to be heaped with both the responsibility and the expectation to weigh in on behalf of all women or POCs.”

And while all this yelling take place in the digital sphere, it absolutely has an impact in the physical world. “Twitter has made it almost impossible to go into a movie without having some understanding of the critical consensus around it,” says Hans. “It can be intimidating to pluck up the courage to offer a contrarian opinion. I know I’ve questioned whether I’ve read a film correctly because I haven’t agreed with the voices speaking the loudest about it.” (To say nothing of the fact that Twitter isn’t exactly a safe space for marginalized voices to speak up.) Though the answer might seem to be “log off,” it’s a precarious risk. “It feels like you have to be part of the conversation or risk disappearing,” admits Atkinson. “Those demands can be exhausting but ring a bell for women. We know what that tweeting and additional work to the criticism itself looks like — we’ve been doing emotional labour for years.”

So, what now? As Bastién told me, “Film criticism needs a major reawakening.” But if history has proven anything, this won’t happen without forcing difficult conversations: ones about race, sexism, bias, and power. Questions that require an arts community that fancies itself to be progressive and Woke™ to do some serious introspection and work. “Male critics like to believe they’re liberal because they retweet women and POC,” says Bastién. “But who are you recommending for jobs? What films are you championing?” A point that’s reinforced by Hans: “Hire more people who aren’t white men! It’s actually that simple. There is no dearth of brilliant, incisive women writers (and POCs) who have a deep knowledge of film.”

Until the film community starts to examine its biases, there will always be the sense that certain folks are allowed in the inner circles of cinephilia and other are going to be left out. To change this will take time, but I’ve given too much to film, and love it too much, to fully give up. As Mayer says: “Unconscious bias can be used as a get-out clause by a white man — but I’m a white, cisgender woman, so I do the fucking work. I have to learn, let other people speak and acknowledge my own ignorance.” We can start there, and in the meantime take inspiration from Bastién: “Instead of wasting my time arguing on Twitter, I’m going to pitch this [argument], make money, and prove I’m a better writer.”

Kiva Reardon is a film critic, a Programming Associate for the Toronto International Film Festival, the co-host of TIFF’s Yo, Adrian podcast, and the founding editor of cléo, a film journal informed by intersectional feminist perspectives.