Emily Harrold has directed documentaries including “Checkers in the Afternoon.” Her films have screened at Tribeca Film Festival, the Melbourne International Film Festival, and the Telluride Film Festival, among others. She is a member of New York Women in Film and Television and Film Fatales.

“While I Breathe, I Hope” will premiere at the 2018 DOC NYC film festival on November 11.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

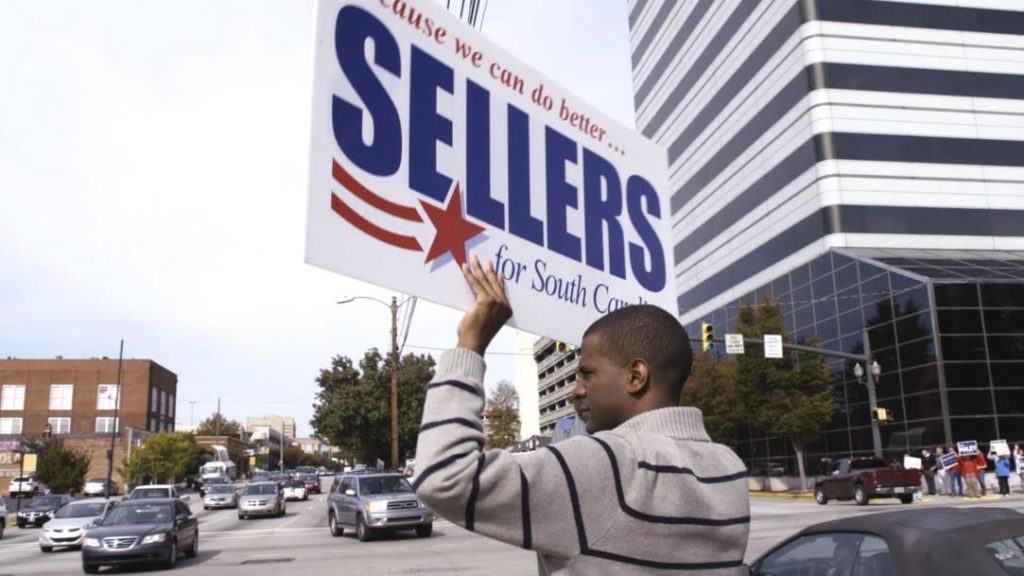

EH: “While I Breathe, I Hope” is a story from my home state of South Carolina. The film explores, through the experiences of South Carolina politician Bakari Sellers, what it is like to be young, Black, and a Democrat in the American South. We follow Bakari through his 2014 race for Lieutenant Governor, as he deals with the aftermath of the Charleston Massacre and the removal of the Confederate Flag in 2015, and as he begins to chart a new course in Trump’s America.

Through Bakari’s experiences, the film explores the legacy of race in American politics.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

EH: I was drawn to this story in large part because I saw something happening in my home that I thought was an incredible story that encapsulated the legacy of racism in the United States that wasn’t getting national attention. I knew if I didn’t follow what was unfolding, no one else would.

I was also very intrigued to see how Bakari’s family legacy of Civil Rights would make it possible to compare the past with the present and explore how far — or maybe how little — we’ve moved on from Jim Crow.

W&H: What do you want people to think about when they are leaving the theater?

EH: When white people leave the theater, I want them to feel like they understand just a fraction more what it is like for people of color in this country to struggle to fight for equal footing.

When people of color leave the theater, I hope they feel like their perspectives are being heard and appreciated.

And when anyone of any background leaves the theater, I want them to believe that even if we have collectively fallen down as a country, we still have hope for tomorrow.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

EH: The biggest challenge in making this film was staying dedicated and having faith that I could do this and that there was an audience for the film. I was rejected by most major grants, I couldn’t find any funding from arts organizations in South Carolina because they viewed the film as too politically risky, and I often was having to work myself ragged in order to balance a full time job — which I needed to pay for the film — and the demands of making an indie feature doc.

But every time I felt this way, I would find a way to remind myself that I was doing what I loved. I was getting to make a movie, and I was telling a story I cared about. And that kept me going.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

EH: Funding in the documentary world it the worst thing. It is something that seasoned filmmakers with Oscars to college students making their first short struggle with at all turns. And that is a problem. I was no different with this film. I went into the project, in retrospect, quite naive. I thought I had a fundable film and that we’d raise the budget with no problem, but as grant rejection after grant rejection rolled in, I realized that wasn’t going to happen.

I received one grant from the New York State Council on the Arts — a life saver. And I was very lucky to get a number of investments and donations. These coupled with my own money and very, very generous collaborators meant that I was able to finish the film. I still have quite a bit of credit card debt that I hope to work off in the coming years.

W&H: What inspired you to become a filmmaker?

EH: I don’t know if there was a moment of inspiration that made me realize that I wanted to be a filmmaker. It was more a series of events that, in retrospect, show that being a filmmaker was my path from the beginning.

In second grade, I turned a marine biology project into a movie. In eighth grade, our team project about “The Odyssey” ended up being me and my friends re-enacting a chapter of the book. In ninth grade, our current events presentation turned into my own brand of national news — which I played on a VHS tape for the class. By high school, I was always filming. I had a tiny handycam that fit easily into a purse.

I think I’ve always loved being able to document reality and shape it into a story. And I’ve always loved how movies can bring different worlds alive. In documentary I have been able to marry all of these together into a truly fulfilling career.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

EH: The best advice I got was from Marco Williams, who is one of the EPs on this film and my former NYU professor. I’ve learned so much from him. In the filmmaking process, you get a lot of notes. And I wanted as many notes from as many different people as possible. But what happens when you do that is that you get so many notes, that you can get lost in them. I will never forget Marco advising me to only take notes that I viscerally react to. Those are the notes that help you see the film in a different way and ultimately make the film the best it can be.

I think the worst advice I have gotten — also around notes — has been to try to shape the film into something I didn’t originally intend and something that I didn’t have. I’ve found that those kinds of notes are ones that you get often — and ones I’ve learned to ignore.

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

EH: I would advise other female filmmakers to not see themselves as a “female” filmmaker and just see themselves as a filmmaker. I don’t approach my projects or subjects thinking about how because I’m female I’m going to tell this story a certain way.

On the flip side, I also think you have to be aware of how the world sees you. And that there are still many people who will see you as female first. Be aware of that, but never, ever let it hold you back.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

EH: This is probably going to majorly date me as a millennial, but “Bridget Jones’s Diary” by Sharon Maguire is my favorite movie directed by a woman. There is something about watching this movie that gets me every time — and I’ve watched it a lot. It is a pick-me-up after a bad day, a fun movie to watch with friends, and also one that after finishing, you feel like you can conquer the world.

Bridget isn’t just a character on-screen: she is a real person dealing with real things, something that could only have been accomplished by having a female director who knows what it is like to be a 30-something adult in a big city trying to keep it all together. It is a movie I go back to often and one that never disappoints.

W&H: Hollywood and the global film industry are in the midst of undergoing a major transformation. What differences have you noticed since the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements launched?

EH: I think people are more aware right now of their bias. I think even a few years ago, it was hard to admit — even among friends — that something unfair was happening because you were female. And even harder to call people on it.

I think the movement has made me more aware of my own perceptions and also how I’m perceived as a young woman filmmaker. There have been more than a few experiences where I’ve looked back and wondered if it would have played out the way it did if I was a man.

Right now, there’s more of an effort being made to equal the playing field. It has been exciting to see this attention brought to the issue. My hope is that this continues and the results are a future where we see more and more women directors succeeding on their own terms.