Karlyn Michelson is an Emmy Award-winning multimedia producer and video journalist. (AFI)

Charlie Victor Romeo is playing AFI as part of the American Independents program.

Women and Hollywood: Please give us your description of the film playing at AFI.

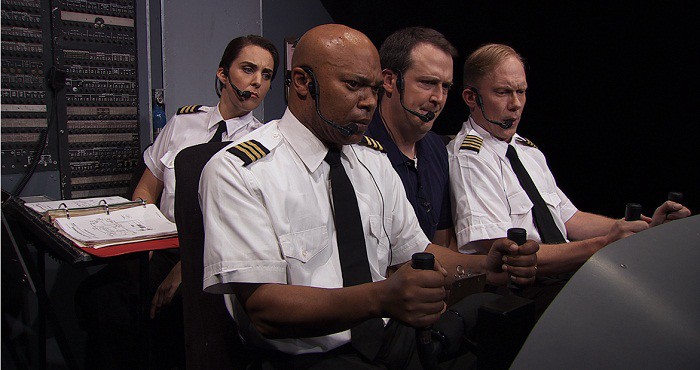

Karlyn Michelson: Derived entirely from the transcripts of real black box recordings, Charlie Victor Romeo uses the hyperreality of 3-D to put the

audience in the cockpit of six aviation emergencies. It is a gut-wrenching, unrelenting revelation of the human struggle at the height of crisis.

WaH: What drew you to this story?

KM: Movies about airplane crashes usually inspire images of explosions, screaming passengers, parts of the aircraft whizzing through the air — all of the

cinematic tools that filmmakers generally use to communicate the intensity of an experience to the audience. Charlie Victor Romeo does none of

that. The minimalist nature of the piece focuses the audience on the humanity of each situation. We’re not watching stereotypical heroic archetypes. We’re

hearing the words of real people who grappled with real events, people who carry the responsibility of our lives on their shoulders every time they take

off. To me, the result is far more harrowing, and haunting, than a visual simulation could ever achieve.

WaH: What was the biggest challenge?

KM: The biggest challenge was shooting in 3-D. An indie budget meant we had three days to shoot the film, which limited the number and type of camera

setups. But more than that, I wrestled with how to use 3-D as an aesthetic and storytelling device. 3-D is generally used to emphasize planes of action:

multiple objects moving in the frame. We had a single, completely static set. 3-D is a great way to highlight a lush, complex landscape. Our visuals are

stark and minimalist.

Claustrophobia is a key element of Charlie Victor Romeo. The crew and passengers are trapped in their airplanes. The audience is confined to

small, dark space. Even the concept of a black box connotes entrapment, enclosure, something permanently locked in. And so we used 3-D to heighten that

claustrophobia, to close the gap between the audience and the characters on the screen. If we did our job right, there’s no escape from the crises

unfolding before you.

WaH: What advice do you have for other female directors?

KM: I find this question distressing. The number of women directing films is still appallingly low, but the idea that female directors should see

themselves as a different entity than male directors is a flawed premise. I’ve never behaved as though being female influenced the trajectory of my career.

I hope that women don’t view themselves any differently than their male counterparts. The only thing I’d add is that as women, we should be aware of this

on-going disparity and we can all do our part to recognize and empower other talented women.

WaH: What are the biggest challenges and or opportunities for the future with the changing distribution mechanisms for films?

KM: Before these changes in distribution mechanisms, it was very difficult to make an independent film available for viewing on a large scale. Now it’s

easier than ever to make our films available to millions of viewers — and that’s exciting! At the same time, while it only takes an upload on the Internet

to make our work accessible, getting the audience to pay for it is another matter.

WaH: Name your favorite women directed film and why.

KM: Don’t make me pick just one. The films of Maya Deren come to mind. Certainly Kathryn Bigelow has done amazing things, as has Lynne Ramsay. But I keep

coming back to Debra Granik’s Winter’s Bone, which was my favorite film of 2010. I’m a huge Film Noir nerd, and there’s something wonderfully dark

and emotionally claustrophobic that harkens back to Film Noir. It also uses a very small and simple story to reveal larger truths about the human

condition, which I aspire to in my own work.