Alla Kovgan is writer, director, and editor who was born in Moscow. Her film “Nora” received 30 awards and was broadcast worldwide. She co-directed, wrote, and edited the Emmy-nominated “Traces of the Trade,” “Movement (R)evolution Africa,” and edited “My Perestroika.” Her first VR piece with the Finnish music duo Puhti, “Devil’s Lungs,” won Grand Prix at the Vienna Shorts Festival, which made her an artist-in-residence at Vienna’s Museum Quarter 21 in 2019.

“Cunningham” will premiere at the 2019 Toronto International Film Festival on September 6.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

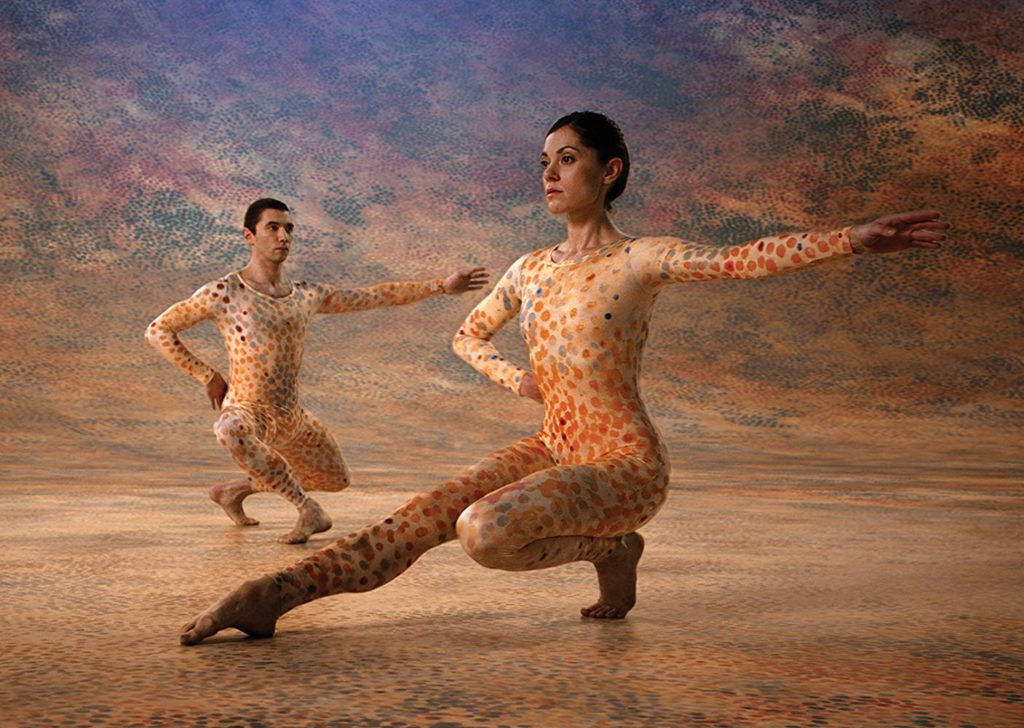

AK: “Cunningham” is a 93-minute feature that I refer to as a 3D cinematic experience about legendary American dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham, created through interweaving his iconic dances and never-before-seen archival treasures between 1942 and 1972, an era of risk and discovery for Cunningham and his collaborators, composer John Cage and visual artist Robert Rauschenberg.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

AK: A formalist at heart, I am drawn to the genius of Merce Cunningham –– the intricacies of his mind, the approaches he invented while making his dances, and his philosophy that he followed, living his life, and re-defining ideas about being human.

I am particularly moved by his story, an incredible triumph of the human spirit. During the first 30 years of his career — between 1942-1972 — he persevered, with great determination and stamina, to make dances against all odds. He was always ready to go outside himself, to place himself in unknown situations, and find new solutions. All this took place in a unique artistic climate, during the 1950s and 1960s in New York, when Cunningham and his collaborators were “united by their poverty and ideas” and art and life had virtually no separation for them.

Cunningham’s dances evoke a sense of timelessness, a space in between rational and irrational, intellectual and emotional, immediate and eternal, that truly “renews” us. Yet I never imagined working with his choreography on film because of the complexity of his choreographic structures and his infinite explorations in time and space.

When I discovered 3D cinema, my views changed. 3D offers interesting opportunities, as it articulates the relationship between the dancers and the space, awakening a kinesthetic response among the viewers. It also favors uncut choreographed shots, moving camera, and multiple layers of action in relation to the setting––everything that allows working with Cunningham’s choreography on screen in new ways.

I always think that, had Cunningham been alive, he would have worked with 3D. He embraced every technological achievement of his time from 16mm to video, computers, and motion capture, and it is because he often yearned to free dance from the constrictions of the proscenium stage. After all, he created over 700 Cunningham Events, performances arranged out of excerpts from different works, which were adapted for a specific location, whether [it was] a gym or a museum or city plaza, so that the dancers could be seen from every possible direction.

The project came about when the Dance Films Association got a Rockefeller Foundation grant to make a film about a New York-based choreographer using 3D technology. This coincided with the last performances of the Merce Cunningham Company in 2011, which subsequently disbanded in January 2012. Watching these dancers, I realized that they were the last generation to embody Cunningham’s spirit. He brought them up himself. No future dancers will ever lay claim to this direct lineage to him.

In addition to all the virtues of bringing Cunningham and 3D together, it is the feeling about the inevitable ephemerality of dance and these dancers’ presence that pushed me to embark on this journey. I felt urgency to give Cunningham’s work another life on film translating his vision, and re-imagining it in 3D cinema.

W&H: What do you want people to think about when they are leaving the theater?

AK: We had a few test screenings and I have seen audiences leaving transformed and moved, as though they discovered something new. That is the best reaction I can hope for. I hope that “Cunningham” will demystify what dancers do every day and what it means to be a dancer. Somehow, dance is always the underdog of all art forms and yet, it is something very fundamental and basic. Everyone can relate to it. After all, we all know how to move our bodies. And when we move we feel alive.

Cunningham was never an elitist although he was part of an American artistic elite. He stayed focused on the dance itself, weeding out anything that was in his way. I hope that the audience has a new experience of Cunningham’s work and of his story. Many people remember Cunningham as an old man; he died at the age of 90. I really wanted to bring back the story of how he became Cunningham through his work back in the day, which still feels so contemporary today. He was a true visionary.

To me, he is also very American, in the best sense of the word, and that is something to celebrate. He is completely self-made, he and his collaborators were devoted to their ideas, and persevered for decades against all odds. All they had was each other. I find it very moving and courageous. Their journey gave me a lot of strength to have faith in my ideas, to continue, and never give up. I hope that the audience will also feel inspired.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

AK: The project has been in the making for almost seven years and I think that it took four of those years to find and fund a model that would allow for it to happen. This was the biggest challenge.

In the dance world, Merce Cunningham is deeply revered. But dance funding organizations felt that they should support living choreographers and their work, which I felt was fair enough, although it did not make things easier for us.

In the film world, nobody knew who Cunningham was. If I named Cunningham and there was no reaction, I brought up the name of the composer and his partner John Cage. If there was no reaction, I mentioned Robert Rauschenberg, Cunningham’s collaborator. His name sometimes got a strange reaction. Once somebody asked, “Is that the guy who made the soup can?” I corrected them, explaining that soup can painting was made by Andy Warhol, but Cunningham collaborated with Warhol, too. Warhol’s name was the only one that consistently got a response. I always knew that the modern dance world was quite marginal, but I was puzzled about a basic lack of knowledge about music and visual arts. In retrospect, this ignorance convinced even more that I should continue with the project.

There was a lot of overall distrust from the film world at the beginning. When I said that I would like to make a 3D film about an avant-garde choreographer, most film people thought that I was simply nuts. Some expressed their doubts openly: “You? You would like to make a 3D film?” And then a set of statements were thrown in such as “How are you going to do it if you do not have 3D experience?”; “3D is passé. It is too expensive”; “Who is going to fund this?”; “It will never happen.”

I was never afraid of technology. Besides being an editor for 15 years, I have been a part of several interdisciplinary collectives and had to learn all kinds of technologies, from live video mixing to multi-screen stage projections and so on. All these questions pushed me to dig in deeper and always find answers.

Things started changing when “Cunningham” won the Best Pitch Award at the 3D Financing Forum in Liège in 2013. This was already after we had six weeks of rehearsals with Cunningham dancers and had made a 3D test. Film industry people started realizing that Cunningham and 3D were a very good fit. At that point, everybody started comparing “Cunningham” to “Pina” by Wim Wenders, a 2011 3D film about Pina Bausch that was nominated for an Academy Award.

I could answer all their questions as to how “Cunningham” was different, but the doubts remained: “Well, although your pitch is convincing, you are not Wim Wenders!” Indeed, I was not, and that was something I could not change. But what we could do was to continue, following Cunningham’s life motto: “The only way to do is to do it.”

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

AK: There were a lot of ups and downs. At first, we had support from the Rockefeller Foundation and Dance Film Association. This was the seed funding. Then Kelly Gilpatrick and Derrick Tseng were selected to take part in the Trans-Atlantic Partnership program through IFP New York. Kelly went and met French producer Ilann Girard, who came on board and suggested to form a co-production. I wrote the script and Ilann applied to CNC in France, similar to the NEA in the U.S., to make a proof-of-concept pilot.

In Liège, Kelly and I met German producer Helge Albers, who liked the project and also joined the co-production. Kelly also brought Stephanie Dillon from Minneapolis on board as an EP. Her contributions, together with the awarded CNC grant and funding from my family and friends, enabled us to create a proper 3D pilot.

Then my dear friend and colleague Elizabeth Delude-Dix also came on board as a producer to boost support from foundations and individuals. We worked on both fronts in the US and Europe. The U.S. tax-deductible contributions are great because they come without strings attached. We could use them freely for development; the European funds always had certain obligations. With the pilot and a strong treatment in hand, Helge applied to German national and regional funds, and most of them chose to support the project.

It became even more clear that the project would be primarily European with Germany at the helm. The tipping moment was at IDFA market in Amsterdam, when Helge, Elizabeth, and I met Oli Harbottle from Dogwoof. It was love at first sight and Dogwoof came on board as a sales agent soon after.

With Cunningham centenary approaching in 2019, we could not postpone the shoot any longer so we decided to film, despite the financing gap. In our estimates, the film budget should have been at least 25 percent higher. But there was no time to raise more financing, hence we are still struggling.

W&H: What inspired you to become a filmmaker?

AK: I was born in Moscow and my first background was in information science and linguistics. Verbal language was never satisfying enough, so I began exploring video art and then filmmaking. I think of cinema as a language that allows one to communicate across cultures and artistic disciplines, provoking, challenging, and moving people all at once. For that reason, I felt strongly that I wanted to work with and in cinema.

My first craft in the film world was editing. Directing came later when I felt that I had something to say of my own.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

AK: The best advice was to continue, to surround myself with like-minded and supportive people, to have faith in my ideas no matter what. The worst was to let go, it would not happen anyway. In retrospect, the worst advice weirdly helped me to get stronger, pushing me to defend my ideas and counter negativity with generosity, which in most cases is disarming.

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

AK: Continue working hard and do not to give up. Listen to those who offer support — like [American soccer star] Megan Rapinoe said — and ignore those who doubt and undermine.

I would also advise not being afraid of exploring new technologies, stepping into the unknown, defying conventions, striving for perfection, and yet being flexible and adaptable to the situations, if that does not jeopardize the filmmaker’s integrity.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

AK: I always loved Chantal Akerman’s films. I saw “Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles” for the first time in a class about women directors taught by a wonderful film theory professor, Linda Dittmar, at UMASS. I was very moved by the way this film dealt with time – women’s time. It was a lot about daily routine, waiting, and the claustrophobia of it all. Only a woman director could have made that kind of film. It had a female sensibility.

I have many other heroines, from Shirley Clarke and Maya Deren to Claire Dennis and Sally Potter.

W&H: What differences have you noticed in the industry since the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements launched?

AK: The biggest challenge for me as a woman director is that my male colleagues are often inclined to question and doubt my decisions. It is interesting it never happened when I worked as an editor. They often feel entitled to offer a lesson without realizing that they are doing this. It takes a lot of energy to explain and defend myself, which is draining and quite annoying.

Before the #MeToo movement, I accepted this patronizing behavior and tried not to pay attention. Now I feel much more empowered to respond with a simple question: “If I were a 50-year old male director, would you tell me all these things?” This response usually provokes a pause and hopefully, brings a new beginning.