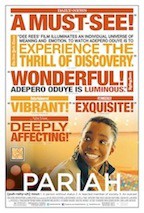

Dee Rees’ debut film, Pariah, has rightfully been celebrated for its tender coming-out and coming-of-age story of a shy yet sexually curious 17-year-old African-American girl, Alike (Adepero Oduye).

An unprecedented black LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender) success at the Sundance Festival in January, the film was immediately picked up by Focus Features for distribution and has since received two nominations for the Spirit Awards, which recognize independent film. In November, Rees was awarded breakthrough director of the year at the Gotham Awards.

Clearly, the movie’s positive critical reception owes much to the brilliant dramatic performances of newcomers Oduye and Pernell Walker, veterans Charles Parnell and Kim Wayans, Bradford Young’s beautiful cinematography and Rees’ subtle yet sophisticated depiction of Alike and her middle-class African-American family’s coming to terms with her lesbian identity.

But Pariah is also indebted to a cadre of often overlooked but no less important documentaries and coming-out films released during the height of black lesbian filmmaking from 1991 to 1996.

In 1993 filmmaker Michelle Parkerson wrote about the birth of a “new generation” of gay and lesbian filmmakers of color whose work challenged stereotypes and stigmas about black lesbian and gay lives on the big screen. Filmmaker Yvonne Welbon, founder and director of Sisters in Cinema and curator of the “Sisters in the Life” black lesbian transmedia project, calls 1991–1996 the “golden age” of a black queer cinema.

“That was the period of time when we had the most women producing the widest variety of work,” Welbon said in an email interview. “Approximately 50 percent of all work produced was made during that five-year time period. Very little work is being produced today by out black lesbian media makers. So maybe Dee Rees is part of the trend of the mainstreaming of niche content that we see happening across all media platforms.”

In her essay “ ‘Joining the Lesbians’: Cinematic Regimes of Black Lesbian Visibility,” film critic Kara Keeling attributes the rise of these self-identified “black lesbian films” to their roots in the larger social movements of the late 1960s and 1970s. These filmmakers not only were children of the civil rights, black power, women’s and lesbian and gay movements, but also grew up as beneficiaries of a more nuanced identity politics with which they infused their work.

Moreover, this golden age of black lesbian filmmaking should be considered part of the new wave of black cinema that included Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It and Jungle Fever, Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust and, of course, Marlon Riggs’ Tongues Untied and Black Is … Black Ain’t, two groundbreaking documentaries that explored racial and sexual identities.

While Parkerson has been making films since 1973, her most notable films — Storme: The Lady of the Jewel Box, the story of Storme DeLarverie, emcee and male impersonator at the Jewel Box Revue, the first integrated gender-impersonation show; and A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde, co-directed with Ada Gay Griffin — were released during this heyday of black lesbian filmmaking.

The most critically acclaimed movie of this period was Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman, a clever mocumentary about a black lesbian filmmaker researching the life of a relatively unknown black actress who played “mammy roles” in the ’30s. The main character, Cheryl (played by Dunye), discovers that Fae Richards, the actress dubbed “the Watermelon Woman,” was actually in a sexual relationship with the white female director, Martha Page, and was part of a vibrant underground black lesbian community in Philadelphia throughout her life.

The vast majority of black lesbian films made during the golden age were documentaries, such as Aishah Shahidah Simmons’ coming-out short films In My Father’s House and Silence … Broken; Jocelyn Taylor’s Like a Prayer, Looking for LaBelle and Bodily Functions; and Welbon’s Living With Pride: Ruth C. Ellis @ 100. However, Dunye’s film stood out because it was a fictional film that featured a black lesbian protagonist and landed a distribution deal with First Run Features.

Since Watermelon Woman’s release in 1996, there have been more than 20 feature films directed by black lesbians. However, like most women in Hollywood, black lesbian directors do not have access to the necessary networks, capital or resources to have their films made and distributed for mass circulation.

A recent article, “Why the Odds Are Still Stacked Against Women in Hollywood,” paints a pretty dismal picture. Despite being 50.8 percent of the U.S. population, female directors make up only 13.4 percent of the Directors Guild of America, and women hold only 16 percent of powerful behind-the-scenes jobs, such as producer, director, writer and editor.

Add the layers of being both African American and lesbian, and the dearth of opportunities in Hollywood becomes even more dire. In this context, Rees’ Pariah is already a marketing success.

This is partly because of the savvy of its producer, Nekisa Cooper, who had an illustrious career working in brand management for such companies as Colgate-Palmolive, L’Oréal and General Electric. It was Cooper who helped brand Pariah as a universal coming-of-age story. It is also because of Rees’ access to Spike Lee, her former New York University film-school professor, who was script adviser and executive director for Pariah.

But mostly Pariah is the beneficiary of Rees’ talent and a slowly increasing visibility of complex LGBT characters in both independent and mainstream Hollywood films. More important, the buzz surrounding Pariah (and other films, such as Ava DuVernay’s recent I Will Follow) indicates a small though significant shift in the exploration of the inner lives of black women — their sexual desires, contradictory emotions, lost loves and found selves — on the big screen.

This alone gives a new generation of black lesbian filmmakers, such as Tiona McClodden, director of the 2008 documentary Black/Womyn: Conversations With Lesbians of African Descent, reason to be excited. “After Pariah,” McClodden said in an interview, “it might be a little easier for more of these types of film to be made. I hope it gets even more recognition and award nominations. So far there hasn’t been a show of something that has been commercially successful in this genre, so this is why Pariah is so important.”

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Salamishah Tillet is an assistant professor of English and Africana studies at the University of Pennsylvania and the co-founder of the nonprofit organization A Long Walk Home Inc., which uses art therapy and the visual and performing arts to end violence against girls and women. Follow her on Twitter.

The was originally posted on The Root. It was reprinted with permission from the author.