Why are so few women in top leadership positions in theaters and how can these numbers improve? HowlRound, a commons by and for people who make performance, has shared new research seeking answers to these questions. The study was conducted by Senior Scholar Sumru Erkut, Ph.D. and Research Associate Ineke Ceder of the Wellesley Centers for Women (WCW) at Wellesley College.

The three-year study follows WCW’s November 2015 report on women’s leadership in theaters that were members of League of Resident Theatres (LORT) in the United States, AKA the large regional theaters.

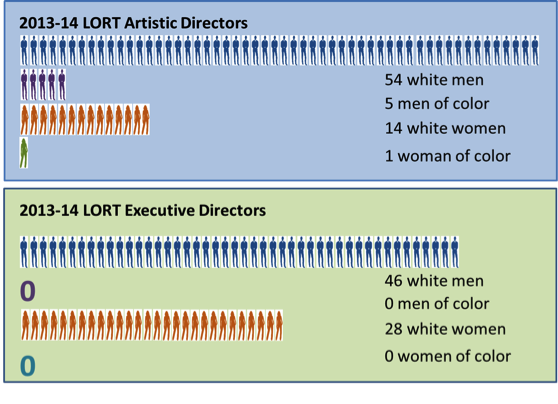

Erkut and Ceder report, “At the time, we wrote that women’s representation in leadership of these theaters had hovered around 25 percent for many years. In 2013–14 when we started this study there were no executive directors of color, female or male, and only six people of color had artistic director positions — five men and one woman.” And unfortunately “not much has shifted since then.”

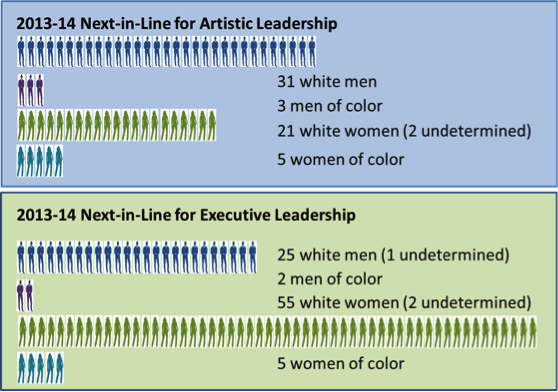

When Erkut and Ceder examined those who filled positions “just below leadership” within the 74 theaters in their sample, they realized that this group was “more gender-balanced” than leadership positions. That would suggest that “there are plenty of women on the pathway to leadership by virtue of their positions.”

After interviewing a random group of individuals in these “just below leadership” positions, Erkut and Ceder concluded that “the aspiration to leadership among women and men does not differ.” Consequently, they ruled out a “pipeline issue,” and instead emphasized the existence of “a glass ceiling, a metaphor for the barriers facing women stuck at middle management where they can see the top but cannot reach it.”

There appears to be much more comfort with hiring women in the role of Executive Director rather than Artistic Director. In the film world, an Executive Director could be compared to a producer, whereas the Artistic Director is more like the director. While the Executive Director and Artistic Director work together, it’s the latter that’s known as being the visionary. Just like in movies, in theater, there’s a lack of trust in women’s vision.

Five major issues were identified that need to be addressed by the field: leadership selection; work-life balance; culture fit; mentoring; and affordability

A number of problems can be attributed to familiarity and trust during the leadership selection. “Hidden behind a gender-and race-neutral job description is an expectation, grounded in a stereotype, of what a theater leader needs to look like: white and male, because white and male leaders have been the long-standing majority of those in top positions,” Erkut and Ceder observe.

They elaborate, “Expecting an artistic or executive leader to be a particular type is a subtle but strong bias when evaluating a slate of candidates. This can steer selection committees toward unconsciously or unintentionally focusing on those they had already envisioned could be trusted to do the job.” As one board member said, “Men tend to hire men because they grew up with men. Decision makers [on the board] have a business background. It’s a vestige of [whom] you are comfortable with. You’d want the best person in charge [of the theater]. Men are more comfortable with men.”

We want to remind people of the Center for Media, Diversity and Social Change’s work on women directors. The problems for women in film are very similar to the problems for women in theater.

Here are some excerpts:

When industry leaders think director, they think male.

Conceiving of the directing role in masculine terms may limit the extent to which different women are considered for the job.

Putting female directors on studio lists is limited by stereotypes.

…reliance on stereotypes creates decision-making biases that weaken women’s opportunities.

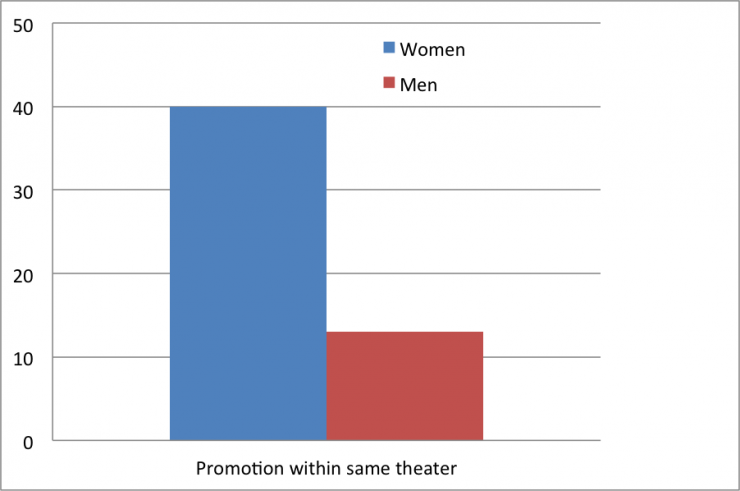

Decision makers often end up considering men as the best candidates to be in charge of a theater, so Erkut and Ceder examined “how lack of familiarity — and, directly associated with it, lack of trust — stand in the way of diversifying top leadership.” The single pattern in hiring preferences that favored women “was that female artistic directors had been promoted into their leadership position from a lower position within their own theater at higher rates than men (40 percent versus 13 percent).”

Erkut and Ceder interpret this exception “in the context of greater familiarity generating trust. When hiring from within the theater, a female candidate was not an abstract, unknown entity; rather, those who made the hiring decision knew the quality of her work well and were therefore able to trust her as their candidate for leadership.”

But “thirty-five percent of the boards of the 23 highest-budget theaters (over $10 million) trusted a man to be able to run their larger organization as the executive leader than he had before” whereas “only nine percent of these theaters’ boards trusted a woman to run a theater larger than her previous place of employment.” So “trust in ‘potential’ was reserved for men, especially for running high-budget theaters.”

Erkut and Ceder offer a number of recommendations for boards of Trustees and industry leaders for how to make the hiring process more inclusive, such as acknowledging, confronting, and correcting gender and racial bias, and ensuring that search committee membership is diverse.

The study considers how “requirements for a successful life in the theater (which may include extensive travel, and long and irregular hours) can be barriers to participation for caregivers (who are mostly women) and more importantly operate as hidden biases, which quietly affect the hiring or promotion process,” and proposes ways to address the work-life balance for caregivers, such as “consciously instituting and advertising family-friendly policies.”

Erkut and Ceder also emphasize the significance that mentoring plays in these numbers. The study notes that upward mobility in theater is typically based on “the apprenticeship model,” and “people who aspire to leadership positions” reported that “they want mentors who ‘look like them,’ who have had similar experiences.”

For instance, someone juggling family responsibilities generally seeks a mentor who facing similar issues, or a person of color may gravitate towards someone “who can speak to the challenges faced by people of color in a field that has predominantly seen white leaders.” Ultimately, “Mentors can help flesh out the variety of experiences an aspiring leader needs in order to become a viable candidate and provide more clarity about career progression which many people below top leadership told [Erkut and Ceder] was unclear.” Mentors have the power to enhance make the career ladder more clear, enhance the visibility of their protegees, and help them network.

Erkut and Ceder presented this research at a conference focused on women’s leadership in theater yesterday. The event was livestreamed from San Francisco, and you can watch the recording on HowlRoundTV.

For more of Erkut and Ceder’s important findings and recommendations, check out the in-depth study. It’s important to note that women of color (and men of color) in particular are underrepresented in these leadership roles, a fact that the study makes clear.