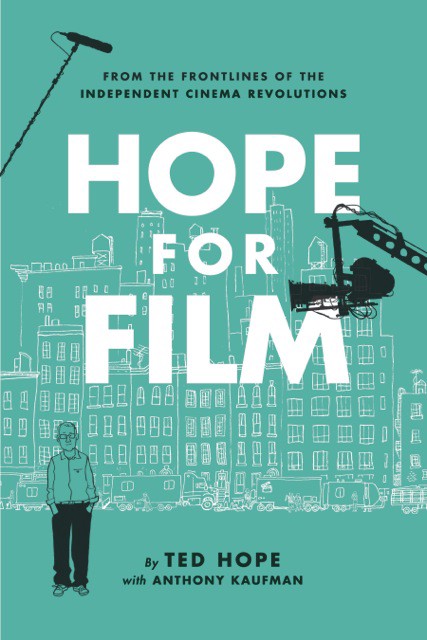

The following is an excerpt from independent film producer Ted Hope’s new book Hope for Film, which was published August 5, 2014.

Nicole Holofcener always

made it clear to me that she would not destroy her life to make her debut

feature, Walking and Talking.

“There’s no way you can

get this movie made in twenty-five days and not work fifteen hours a day,” I

told her.

But she went back to her

cinematographer, Michael Spiller, and they came up with a list of shots for the

entire film, designing a visual style that would also keep the days at a sane

length of around twelve hours. Not every day turned out to be that short, but

you could see the planning that went into it. Originally, I saw it as a

weakness. I thought, “We’re not maximizing our schedule.” But Nicole planned

out exactly what she wanted and how she would communicate it. She could see the

bigger picture, what was best for her team and, ultimately, for her and her

film.

Sometimes, while making

movies, finishing movies, or selling movies, people find it very easy to focus

on the details and lose sight of what’s more important.

I first learned about

Nicole through Mary Weisgerber, who was a location manager and a friend of

mine. Mary had given me Nicole’s student film, an acclaimed short called It’s

Richard I Love. It was a neurotic love story, starring Cynthia Nixon (later

from Sex and the City) and Keith Gordon (who became a director in his

own right). I was coming off my second production with director Hal Hartley,

and although he and I had made two movies in two years (Simple Men and Trust),

I was not yet able to support myself just producing, so I had to find a few

more directors damn quick if I was going to survive as a producer.

Nicole, however, did not

have an agent yet, and I had Mary, who, as I said, introduced us. I met with

Nicole on a sweltering day in New York City, where I had just come from my

first meeting with an agent at William Morris, so I was wearing a tie for the

first time since high school. The heat was uncomfortable, and the tie made me

even more so, but I think the “professional look” impressed Nicole somehow, or

at least camouflaged my own nervousness at meeting a new director.

Nicole had just completed

a first draft of Walking and Talking the day before. I thought the

script was absolutely perfect for me to produce. It was set close to where I

lived. It was a character-focused, situation-based, dialogue-driven humanist

film that was informed by the best of independent cinema — from Woody Allen to

Eric Rohmer to television. It had a joke every five lines, was told from a

woman’s perspective, and was about female friends — something that remains

underserved in cinema to this day. We would also be able to draw on the

incredible pool of actors living in New York at that time — people who could

deliver both freshness and familiarity. We didn’t need stars. We ended up

casting Catherine Keener, Anne Heche, and Liev Schrieber, all of whom, of

course, would later become far more recognizable names.

Walking and Talking was also a story about

young adulthood. Because I was then in my twenties, I identified with the

characters in the story. It celebrated and captured what we were living and

what we loved. As much as independent film in the 1990s was about delivering

stories to underserved audiences — based on race, gender, sexual orientation,

class, and creed — there was another great underserved audience: mainstream young

adults, who were only being served idealized representations of themselves.

Hollywood was not focusing on the everyday, middle-class existence of most

young adults, the small moments, like when your cat dies or you are losing your

best friend. This kind of story hadn’t played out in mainstream movies very

regularly. And this was Nicole’s specialty.

So we developed the

script, which meant constant rewriting — she went through approximately

twenty-five drafts. And the work I did with Nicole on the Walking and

Talking script would set the template for my standard development process

with dozens of filmmakers later. In large part, it starts with a series of

questions: How do you find the theme? What do you want the big takeaway from

the movie to be for the audience? What do you want them to remember

intellectually, and what do you want them to feel emotionally? At a certain

point, Nicole came up with this image in her mind: The character Amelia (played

in the film by Keener) is holding her friend Laura (played by Heche), who is

getting married and starting a new way of life, afloat in the water. That, to

me, was a baptismal moment of surrender and passage. It was about loving

someone so much that you let her go. And that was the big takeaway of the movie

in a single visual and heartfelt instant.

But it was a process to

get there. Once we found this telling scene, and once the theme of love as loss

emerged, we had to make sure that the theme emerged elsewhere in the script.

After we were sure that the script captured the theme, we wanted to look back

at the characters to see how the idea was reflected in their identities and

internal conflicts. Then we looked at how the notion was revealed in the

relationships between the characters. Expanding further, we asked how this idea

exists in the world of the film, in general. The script for Walking and

Talking answered all those questions. And it felt natural and organic, and

funny and emotionally true.

Walking and Talking became Good Machine’s

first project when we incorporated in December 1989, though we had gotten other

movies in production sooner. (Some months later, on a single day, we were

shooting three films, Dani Levy’s I Was on Mars, Ang Lee’s Pushing

Hands, and Hal Hartley’s Ambition.)

We decided that we needed

to make another short to raise industry awareness for Walking and Talking,

because It’s Richard I Love was getting old. So Nicole wrote a

five-minute film called Angry, which was originally titled something

more accurate like Mom, I Am Breaking Up with You. We shot it in two

days: I was the producer, the first assistant director, as well as the caterer,

and I made a frittata with sausage and peppers to boost morale on the set. If

everyone sees that the producer is so dedicated that he’s serving the food, the

crew is more likely to put their heart and soul into it, too. As we had hoped, Angry

got into Sundance, where we planned to use it to promote the feature script

we hoped to make the following year.

But Nicole can actually

thank Hal Hartley — not Sundance — for helping her get the film made. Hartley’s Simple

Men was headed to the prestigious competition section at Cannes, and I

learned that Dorothy Berwin, who headed up business affairs for Zenith, the

company that helped finance both that movie and Hartley’s Trust, wanted

to get a movie going herself. I

told her the story of Walking and Talking, of two female friends and

their fears that one woman’s marriage will break up their friendship. Dorothy

recognized a universal story, one that was messy and funny and unafraid to say

how things were. It would be a perfect project for her to launch her own

producing career.

Even before I got back

from Cannes, I called and asked one of our assistants to put all 120 pages in

an envelope and send it overseas — this was before the Internet. I was always

cutting costs and the fact I was willing to call overseas indicated how urgent

I thought it all was. A couple weeks later, Dorothy called and said she loved

it, especially the scene with the cat suicide. Midway through the film, the

main character’s cat, which appeared mopey all along, jumps out a window. As

far as I was concerned, the scene didn’t advance the story and it didn’t reveal

the character, and I had actually convinced Nicole to cut the cat-suicide

scene a few drafts before. Turns out the assistant had sent the wrong draft, so

Walking and Talking ended up getting financed because of a scene that

had been cut out of the script! It is the sort of beautiful mistake that you’ve

got to love and embrace when it comes. Nicole’s patience, loyalty, and

commitment paid off — we received a million dollars, and we got to make our

movie.

Ted Hope is one of the most respected voices in independent film. As the creator, editor and regular contributor to HopeForFilm.com blog, Hope provides a must-read forum for discussion and engagement about the critical issues faced by filmmakers, artists, and the film industry in today’s global, market-driven economy. A true expert in the field, a survey of his 65 plus films includes many highlights and breakthroughs in independent cinema, including Ang Lee’s “The Ice Storm, “ Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini’s “American Splendor, “ Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu’s “21 Grams, “ Todd Solondz’s “Happiness,” Sean Durkin’s “Martha Marcy May Marlene,” and Greg Mottola’s “Adventureland, “ amongst many others. In 1990 he cofounded with James Schamus the production and sales powerhouse Good Machine, which was sold to Universal in 2002. In September 2012, Hope left a lifetime in New York City to take leadership of the San Francisco Film Society as Executive Director, where he is providing a launchpad for film lovers and filmmakers to participate in the broadest definition of cinema by creating innovative programs for the creation, appreciation and monetization of the art form.