Catherine Gund is an Emmy-nominated producer, director, writer, and activist. Her media work focuses on strategic and sustainable social transformation, arts and culture, HIV/AIDS and reproductive health, and the environment. Her films — which include “Dispatches from Cleveland,” “Born to Fly,” and “What’s On Your Plate?” — have screened around the world in festivals, theaters, museums, and schools, and on PBS, the Discovery Channel, and the Sundance Channel. She is the Founder and Director of Aubin Pictures.

Daresha Kyi is an award-winning filmmaker and television producer with over 25 years in the business. A graduate of NYU Film School, she won a full fellowship from TriStar Pictures to attend the Directors Program at The American Film Institute (AFI) based on her multiple award-winning short film “Land Where My Fathers Died,” which she wrote, produced, directed and co-starred in with Isaiah Washington. She recently served as executive producer of the award-winning short “Thugs, The Musical.”

“Chavela” opens October 4 in NYC, and October 6 in LA and San Francisco.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

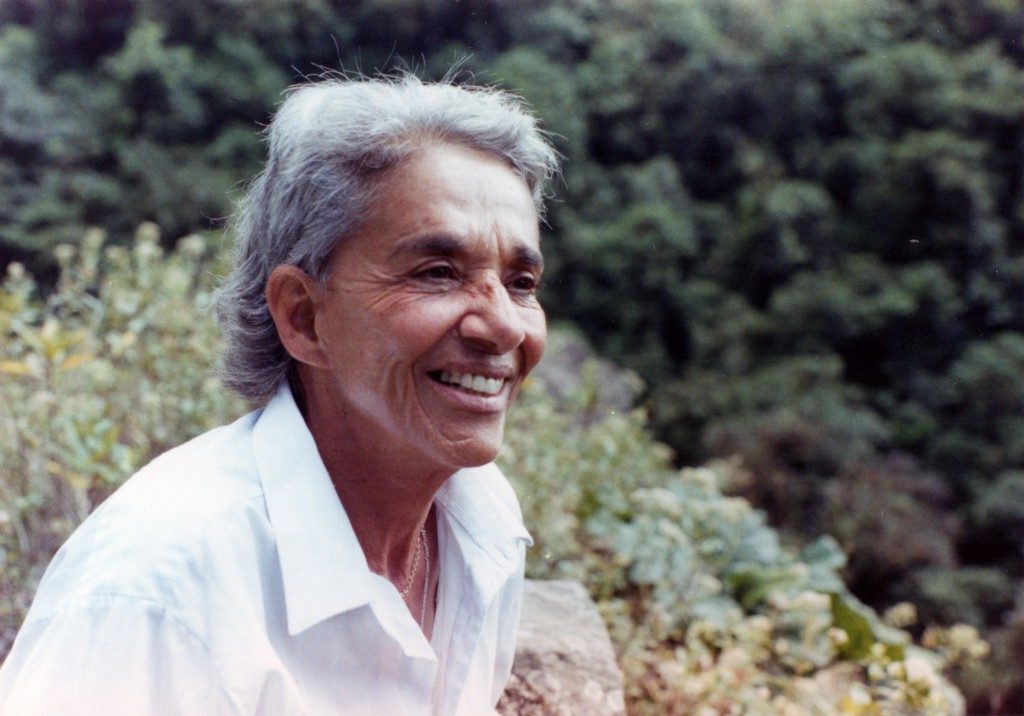

CG: Chavela’s voice and her singular magic transcends space and time, wrenching our souls, tapping into our deepest grief, and our most radiant immortalizing love. She was a badass butch who lived for nearly a century, firmly weaving her own story into the ancestral lines of Latin folks, queers, and women from across the generations who are living today.

DK: “Chavela” is a loving depiction of a badass outsider who dared to stand in her truth at a time when it wasn’t just unpopular, but downright dangerous to be an out, proud lesbian. She sang from the depths of her soul and moved audiences to tears with the raw power of her emotions. This trailblazing rebel defied the social norms and lived life as if it were a rollercoaster ride — soaring to great heights, and plunging into profound chasms — and turned it all into art.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

CG: When my best friend, who was Chicano, died of AIDS in 1990, I fled to Mexico and was introduced to Chavela Vargas’ songs by my new friends who revered her. They saw my video camera, my constant companion, as I captured her concerts in a small hall, and they were determined to interview her.

She invited us to her home in Ahuatepec. The resulting footage sat in my closet in a box for over 20 years. I realize now that Chavela had to finish writing her story so that this film could tell it.

Her music moved me in 1991 and her music moves me today. But her soul and her choices in life are what truly rattle my core, reminding me constantly to live my one life as honestly and fiercely as I possibly can.

DK: I love stories about underdogs who triumph against all odds. Chavela started her career as a homeless runaway who sang on the streets of Mexico City to survive and went on to win a Lifetime Achievement Grammy Award, sell out Carnegie Hall, and serve as a muse to Pedro Almodóvar. It doesn’t get more inspiring than that!

W&H: What do you want people to think about when they are leaving the theater?

CG: I want people to feel love, honestly. I want them to feel like difference is positive, enriching, and generative. I want them to believe in themselves and all of those around them. I want them to know that we each have something to contribute.

Chavela motivates those of us who discover her to fuel our own desires, to transform ourselves into our most honest, brave, and emotional selves.

I want viewers to choose Chavela’s songs when they’re picking the soundtrack of their lives because she transcends and creates empathy, and there will only be justice when there is empathy.

DK: I hope people walk away knowing that it’s never too late to achieve their dreams and that they feel inspired to stand even more firmly in their individual truths, whatever they may be.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

CG: There was so little that got in our way. Chavela blessed this project from day one, 26 years ago. I believe Chavela felt comfortable, different, and engaged by the circle of young lesbians who carried on that conversation with her while I filmed in 1991. She had a reputation for being blunt and cranky, but to us, she expressed her magic, her spirituality, her truth as she spoke about feminism, identity, aging, and love.

Her generosity, brilliance, and candor stuck with me through to the end of the filmmaking process. In fact, I feel like she kept appearing: guiding, sometimes dictating, laughing, promising, consoling, saving me again and again. Full gratitude and recognition to Chavela for making this film with me!

DK: In terms of the creative process, Chavela lived such a full, fascinating life and accomplished so much that it was challenging to decide which aspects of her story should be left out of the film. For example, we were convinced from the very beginning that her participation in the movie “Frida” with Salma Hayek would be a crucial element in the film, but we wound up discarding it completely.

This process of “killing our babies” was sometimes painful, but since the film is 90 minutes long and Chavela lived to be 93 years old there was no way we could focus on every aspect of her life. Once we decided to make a 12-year jump from her triumph at Bellas Artes in Mexico to her being confined to a wheelchair, it made the entire process easier. In hindsight I think it was a wise choice because by that time we had firmly established how solitary and fiercely independent she was which made the impact of her forced immobility even stronger for our viewers.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

CG: I wish there were a more promising answer, a more sustainable road towards making docs that matter, but as usual, we ground out the foundation with grant applications. We received grants from, among others, the NEA, Women and Film, and Frameline.

We also were blessed with angels early on, executive producers Lynda Weinman and Bruce Heavin. Their seed investment was pivotal. We have co-producers and individual donors.

We opted not to do Kickstarter this time — although I did that for “Born to Fly” — because although it was excellent for community building, the funding-to-time ratio was out of balance.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

DK: The best feedback we received came from our composer, Gil Talmi, who saw an early rough cut and said that he was moved by the way we presented the light and dark aspects of Chavela’s persona and story without judgment. Those words solidified something we’d be striving to do somewhat unconsciously and became a guiding principle.

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

CG: Find a nugget that you don’t totally understand. Let the tiny fascination grow with your work and your collaborations. Discover something new so that you can share the power of revelation with your viewers. If it doesn’t interest you, it won’t interest anyone else either. Stick with it.

Find mentors. Work with people who’ve done the work before and never stop yourself from imagining bigger than they do. Without the confines of convention and tradition and reality, your vision will be creative and persistent and beautiful.

If you find any old footage pre-2000, anything shot before we all carried video cameras in our pockets, see what you can do with it — where you can take it, and where it can take you. Cinema is not a very old art form in the scheme of things and there is so much left to be made of it, in form and structure, but also in terms of content and understanding the power of the image and the power of representation.

DK: Trust your instincts and surround yourself with people with similar aesthetic sensibilities who understand and support your vision. Also, hire as many women as possible! We have to support each other in this male-dominated industry.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

CG: My favorite woman-directed film is still Julie Dash’s “Daughters of the Dust,” because she invented a form. With that film, Julie generously released into the film world her creativity and vision. She moved us further away from enumeration of dominant facts or chronology and towards a magical dimension where we are all freer to participate, understand, communicate, and revel in our humanity.

DK: I love different films for different reasons and find it almost impossible to narrow it down to just one! However, there are two films that stand out in my memory, Mira Nair’s “Kama Sutra,” which I loved for the depth of sensuality it captures and Kasi Lemmon’s “Eve’s Bayou,” whose mystical portrayal of a section of black life that is rarely seen I found very inspiring.

W&H: There have been significant conversations over the last couple of years about increasing the amount of opportunities for women directors yet the numbers have not increased. Are you optimistic about the possibilities for change? Share any thoughts you might have on this topic.

CG: “Daughters of the Dust” was the very first film directed by an African American woman to be inducted into the National Film Registry — and that was not until 2003. Fewer than six percent of the films in the Registry are by women.

We need to stop worrying about playing by the rules and nurture women through every step of being able to tell our own stories. When women tell our stories, when we express our truths, the world will break open. We’re not there yet, but that doesn’t mean we should stop trying.

DK: As Frederick Douglass said, “Power concedes nothing without a demand.” It is up to women to drive the change we need within the industry. As they climb the ladder of success, women in positions of power simply must bring other women along for the journey by mentoring and — even more importantly — employing them.

I am particularly inspired by women like Ava DuVernay, who seems hell-bent on creating as many opportunities for other women directors as possible. In the fight for equal representation and equal pay we must agitate, agitate, agitate!