Catherine Hardwicke hardly needs an introduction — she’s been in our lives for a very long time making some great movies, starting with “Thirteen,” and breaking new ground with “Twilight.” Her other credits include last year’s “Miss Bala,” episodes of “This Is Us,” and the music video for Lady Gaga’s “Til It Happens to You.”

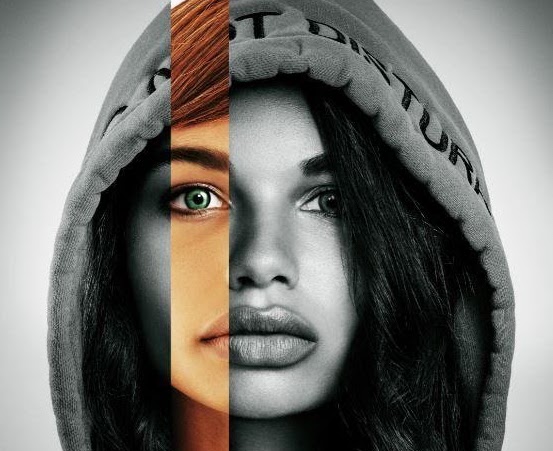

Her newest project is the Quibi series “Don’t Look Deeper,” about a high school student in a world full of robots and AI, who starts questioning if she’s human.

Hardwicke recently joined the Girls Club to talk about directing the series, her career, and kicking off a revolution with “Twilight.”

A community for women creatives, culture-changers, and storytellers, the Girls Club will be hosting more live events and opportunities such as this in the future. We are offering the first month free for those who are interested and identify as a woman. Please email girlsclubnetwork@gmail.com to receive an invitation and let us know a bit about who you are and what you do.

“Don’t Look Deeper” is streaming now on Quibi, with new episodes debuting every weekday through August 11.

This interview has been edited and condensed. It was transcribed by Sophie Willard.

W&H: Can you give us your logline of “Don’t Look Deeper?”

CH: A young girl — a teenager — is going on this journey of self discovery, and unlike other movies I did, like “Thirteen,” what she discovers about herself is pretty mind-blowing. [Laughs]

W&H: To say the least.

CH: There’s humanity, and love, and tolerance, and our love-hate affair with machines and technology — it’s got a lot of things going on.

W&H: Was it a challenge to create everything in under-10-minutes segments?

CH: Yes, that was completely different for me. I’ve worked on some TV episodes — “This Is Us” and things like that — but this could not even be one frame over 10 minutes. So, even if when scripted out you thought it was going to work out perfectly when you shot it, there are some times when you’re making a film that you just want to have a little bit longer, more of a breath, let that scene breathe, let the music play a little longer.

So all of that, we would just chop-chop-chop. We had to make sure it worked. Not just the 10 minutes, but you wanted to be sure at the end of each 10 minutes there was something compelling enough that you wanted to keep watching — a cliffhanger or an emotional turning point, or some moment [where the audience wonders], “What would I do if that happened to me? What would I do next?”

W&H: The actress that you cast, Helena Howard — her face just is exquisite in this. How did you find her?

CH: She had that great movie at Sundance, “Madeline’s Madeline,” and that was in a weird way like “Thirteen” — I met [star] Nikki [Reed], and then I made the whole movie around Nikki. It was the same thing with the director [Josephine Decker]; she made the movie around Helena after she met her. So Helena is very raw and emotional in that film, and I just thought this is an actress who has so much humanity and vulnerability that is going to take us through this journey, that you’re going to love this character.

W&H: The people who created the show, and the writers of the show, did they write it in segments or did you have to cut those beats?

CH: No, [creators] Charlie [McDonnell] and Jeff [Lieber] were interested in exploring short form content, and there were already a few platforms that were doing short form, so they wrote it in the 10-minute segments. That’s what was I think really good about it: it wasn’t like you had to go and stick the scissors into an old screenplay you had, to fit into the format; it was written so that each chapter could have a different vibe at the beginning, it could be nonlinear, it could be a book chapter taking you into something in a new way. That’s what I thought was fun about it.

W&H: And I think it really deals with all the struggles that we’re having about technology, and how technology has become so dominant in all our lives — particularly since the pandemic began, we are relying on technology for connecting with everybody. So, it’s prescient that this is a show that really challenges people to think about technology.

CH: Right, and I thought that it was so fascinating because I have the love-hate affair — who doesn’t? You have your Alexa, you tell her to do something but she can’t do everything that you want her to do, and [I want her] to be smarter but I hate it when she tries to crack a joke — it’s fine lines. You’re just balancing.

I had all electric cars in the show — you might have noticed that they’re pretty much all electric cars — and so I thought I better get an electric car, it’s the future. And of course I want my car to do more, I want it to park for me, and I want that AI to be stronger and better — but then I’m scared of it. I love it and hate it.

W&H: There are 14 chapters in this — some of them are less than 10 minutes but it’s basically movie-length. Did you have enough money to make something like a movie?

CH: That was the idea that [Quibi founder Jeffrey] Katzenberg pitched: we want cinema-quality films on a mobile device. We love to watch YouTube videos and home videos but he wanted another experience available to you. So they gave us enough money — I think it was roughly to make an $8-10 million movie.

W&H: That’s pretty good.

CH: [Laughs] It’s pretty good but we did shoot it in LA, so that takes away a lot of the money, but we had Don Cheadle and Emily Mortimer — beautiful actors — and we had real locations.

W&H: I want to talk a little about Emily Mortimer’s character because she’s a woman in STEM, a scientist, and really struggling with connections with people, and building someone to love, basically. How were you able to get her character to be so rich?

CH: Yeah, I thought that was such a fascinating character. Emily was fascinated because you haven’t seen that character much before — you’ve seen the evil scientist character, but this person has her own deep wounds in her psyche and from her family. We see just little glimpses of that. Maybe she’s somewhere on the spectrum, but she’s also got this desire to be creative, and to create something, and I could relate to that — we get really possessed when we want to make our movies. It’s like blinders — “I’ve got to do this, I’ve got to do all this work on it 24/7,” so you get obsessed with it. And that’s what she does, not really seeing the bigger implications of what she’s doing.

W&H: Right, and Don Cheadle’s character was really interesting, he was suffering from so much loss in his life. Talk about his character.

CH: Well, [about] his character, he said “I’m a broken banana bird.” He’s got enough damage and loss, he was probably already this introspective professor character, and the fact that he lost his child, his wife, his heart is able to love somebody who needs this more than anybody needs it, so he’s more accepting, in a way of the difference.

W&H: What was interesting is the kids are the ones who very easily got over humanity versus non-humanity as a concept. What is a human — that’s the question we’re asking. What makes a person real? I think that’s something we all struggle with on an ongoing basis. Is that one of the themes that you were trying to get through to everyone?

CH: Yeah, I think that’s so interesting, especially now we’ve had this whole awesome movement, Black Lives Matter — how do you see people as the same, and in an inclusive way, instead of as different from me? And so I think that’s part of what [Howard’s character] is struggling with — even at first she saw the other robots as different, and then she has to discover their humanity too. It’s an evolution for everybody through the show.

W&H: Right, and some look more robotic than others — the levels of AI.

CH: Yeah and I think it was fascinating that the writers built that in, that some of them were meant to be clearly robots — you can see the face plate, nobody’s hiding it — but they were human enough, like the uncanny valley. They were compassionate enough that if you were walking down the hallway and you had a bad day, they could maybe come up and give you a hug.

W&H: What were you doing when you had to shut down everything and go into lockdown?

CH: Oh my god, I was on the most fantastic movie. I was in New Orleans, and I was doing a movie that stars Samuel L. Jackson, and Naomi Watts, and 50 Cent, and Pete Davidson. It was a dream job, we were [going to be] starting shooting five weeks from the day that we had to shut down. We were in prep, we had the stunt coordinator, the second unit director, the DP, myself, we had found all the locations — which are amazing in New Orleans.

And on the Friday, March 13 or 14, we were Skyping — back in the days of Skype — with Samuel L. Jackson about his costumes. He was going to go into the costume house on Wednesday and get a fitting, because it’s a period piece, and then by Monday the costume house was closed. We were like, “Oh, that’s weird.” Tuesday, everything‘s closed. So we all had to get on planes and come back.

W&H: So is that just on break and then you’ll pick up hopefully when you can, or is it one of these things that has fallen apart?

CH: Well, we hope it comes back together but it was traditionally financed by foreign sales, at the markets. If you have, [for example,] France is going to give you half a million dollars or something like that, now they don’t know if they can give you that much money anymore; maybe they can only give you half. So, suddenly your budget [gestures diminishing size] because you already made your deal with Sam on what his rate’s going to be. So I think our financiers are just trying to sort through it all, plus how much more is coronavirus going to cost, the rates of business, the whole deal.

W&H: Right, and are they talking about starting up and getting back into it, or is it still in a mode of wait and see? There are different amounts that people are saying it’s going to cost to add for coronavirus protections, and it’s like a completely new business part of the budget now, right?

CH: It is. I’m working on a few other projects, and we’re actually budgeting a show for Snapchat right now, a skateboard show — you see the skateboards? [Points to skateboards hung up on wall in background.] I’ve already done my guys skateboard movie, “Lords of Dogtown,” now I’ve got to do my girls show. So we’re budgeting it, and then of course [wondering] how many locations can you move outside, and not do interior locations if we don’t have to. How few people on the crew could be there? How much time is it really going to take to shoot, as opposed to how much time to test? It’s all in discord. Some shows have started up, and then had to shut down.

W&H: Right, how do you create a coronavirus bubble? How do you create your own pod, or something to keep it safe? Fundamentally, for me — you’re deep in the business — it feels the floor has been taken away, and everyone has to just rebuild from the bottom up to figure out how things are going to work. Things just aren’t going to be the same. I just read today CAA is laying off 40 percent or 50 percent of their staff. Everything’s decimated.

CH: It’s so crazy because I think everybody in the film world is used to being very productive, go, go, go. And as soon as you get a job, you’re just working 24/7 on it — it’s exciting, it’s an adrenaline rush. Or, you’re in development, but you have the hope that this could go, this could shoot if I pull this piece together.

But now, even if you’re talking to actors, they don’t know when they would go back, or they’re committing to multiple things, or they just don’t even want to think about it right now — everybody has a different mindset. It is wild but I’m pretty busy, still developing things, and we’re pitching on Zoom, and all those crazy things.

W&H: Yeah, I read in Screen, they had a “How I’m dealing with working at home” series, and you were in there just two days ago. You were saying that you and your assistant were designing lookbooks, and making pitches. How do you find the Zoom pitches versus the in-person pitches?

CH: I am so used to just being right there in the room and looking at the person’s face, and now when you’re pitching, you have the tiny little squares of pinned people at the top, and you have to scroll back. If you’re talking, you’ve got to be in the moment, so I can’t really be watching, [wondering if] that little person is paying attention. It’s very different but it’s our life so I’m just trying to be positive about it.

W&H: Have you sold anything?

CH: We have a lot of things moving in that direction.

W&H: I hear people are buying, so the optimism is still out there, it’s just that people have to figure out how to make these things. I just want to go back a little: your career started as a production designer, and you’re so creative and artistic, and then you used that skill to become a director. So talk about why your skillset as a production designer enabled you to segue into being a director.

CH: Yeah, I went to architecture school when I was 17, University of Texas, and what you learn in architecture school — and then can apply in productions and in directing — is problem solving. You do your research, you dig deep — in the case of a film director, I’ll go meet the “characters” it’s based on, go visit these worlds. You do all your research, and you’ve got to solve problems because you’re going to have a schedule that’s impossible, you’re going to have a budget that’s impossible, you’re going to have lots of limitations on where you can shoot.

Pre-visualization is another big one for architects, when you have to go out and look at a blank space and go, “Oh, I could build something.” I did the movie “Three Kings” as a production designer, with David O. Russell directing it.

W&H: He sounds like a charmer.

CH: He’s wild, he’s got a lot of energy. We would just go out to the middle of a desert, flat, and I would say, “I’m going to build a town here.” I could hold up the drawing, or hold up some sticks, but I could see it — to me it was very vivid. That idea of pre-visualization — how am I going to stage the scene, how am I going to block it? — all that stuff is directly translatable to directing.

W&H: Did you get any advice from any of the directors that you worked with that you took into your directing career?

CH: Yes. Luckily, at the same time that I was working on their teams, working 24/7 to make their movies great, I would be — on the weekends and in between jobs — taking directing workshops, learning how to use Final Cut Pro, and shooting my little short films, taking acting classes. So all these principles that I was learning, I would watch them in action. I watched Lisa Cholodenko, David O. Russell, Cameron Crowe, Richard Linklater, and then I would ask them questions too and I would see: how do they work with that actor? How did they get somebody to do what they wanted them to? And each director really had a very different style, so I could almost cherry-pick — okay, I like that method, I like that, that might work for me.

W&H: We have a question in here about [1995 film] “Tank Girl,” which seems to have been before its time, and now is a cult classic. Can you talk about “Tank Girl,” putting that together, working with [director] Rachel Talalay? A new generation is discovering it.

CH: Right. “Tank Girl” is based on a very cool comic book by Jamie Hewlett, and it’s that fierce, outrageous woman [character type] that was way ahead of its time — now we see it in “Suicide Squad,” and all that, but we really hadn’t seen that character before. She’s just a big, crazy “fuck you” to everybody, wearing her Target t-shirts and stuff. I remember when I went in there for the job, I thought, “I would die and go to heaven if I get to be the production designer on this.” And I got the job, and I literally got to design tanks, and put a barbecue pit and umbrella on a tank, and weld it together. I got to do airplanes, got to build stuff out in the middle of White Sands, New Mexico.

Every creative idea was encouraged by Rachel and by the creators, so they did not put the brakes on. It was just like, “Yeah, let’s be creative, let’s push the boundaries, let’s push the look.” When somebody is pushing you and not telling you, “Oh no, make it more like this, make it more like that,” we came out of our own imagination.

W&H: Do you think it was ahead of its time, it came too early?

CH: I think it was ahead of its time, people were just shocked to see it. [Laughs]

W&H: Yeah, I think people weren’t ready for “fuck you” Lori Petty, and the whole way that movie came across. I think today it would probably play really well. So, let’s move into “Twilight” lands. You made “Thirteen,” and one of the things that came out of that is that you were cool and that you could talk to young people — I would imagine lots of folks have issues with not respecting them in that way, and giving them agency and things that young people hate about us adults. So, how did you get the “Twilight” gig?

CH: I was on the jury at Sundance in 2007, and then there was a dinner. [I was asked,] “Oh do you want to go see CAA? Do you want to go eat dinner with these guys from Summit?” They [Summit Entertainment] were going to start making original content — they were usually a foreign distribution company — and they said, “We’ve got five screenplays here, we love ‘Thirteen,’ see if you like any of these because we want to start making our own films.” So I read all five, and I just threw them all in the trash. I really didn’t like any of them.

But the next day, I thought, “What was that vampire one that I threw in the trash? I wonder if it’s based on a book.” So I went to the bookstore, got the book, read the book, and I said, “Man, that script that I threw in the trash, it really missed the mark.” People might have heard this but it had FBI agents, Bella was a track star, she was being chased on jet skis by FBI agents. [Laughs]. They went off.

So I went to the meeting, I made a lookbook of how I thought the whole show could be, and I was like, “you’ve got to throw this script in the trash. We have to start over and make it closer to the book. Because what the book has is this ecstatic feeling of falling in love, and we’re going to make that cinematic. I love the forest, the Pacific Northwest — my family lived in Oregon — look how beautiful it’s going to be. No one’s ever seen vampires like this.”

Then they said, “Oh we haven’t even read the book. And we don’t even have the rights to it yet.” [Laughs] But when I got excited that got them excited, too. So they went to Stephenie Meyer: “Catherine wants to make it more like your book,” and that was very positive for her. So we just started going on the track, and since they didn’t think it was going to be a big hit, Paramount put it in turnaround. They said, “We don’t want this project anymore,” and the producers took it to every studio in town — Fox, everyone. Nobody wanted to make it, they said, “This is not going to make any money.” But this young, startup company said, “We’ll give it a shot.”

I think that if they thought it was going to be a big blockbuster, they wouldn’t have hired me, they wouldn’t have hired a woman — there would have been a guy that had done like 10 blockbusters in a row — but we got in under the radar. Nobody believed in it, and so I got the chance to direct it.

W&H: Nobody believed in it because nobody had done it, and seen it be successful, because they just kept perpetuating a cycle of not believing in stories about women. You basically started a revolution — and I’m not going to understate it because you really did — that was the beginning of this understanding that movies with female protagonists at the center, that are not $5, that can have bigger budgets are something that the audience will go see. And so, we are here today with “Wonder Woman,” and this year with five big budget movies with female protagonists, directed by women, that were supposed to be released in 2020. You can track that revolution from “Twilight.” So I think that the reality of that movie was, it was a low budget movie, and women didn’t have access to make movies that cost $100 million.

CH: But it made $400 million. [Laughs].

W&H: It did. And that’s why I feel like that’s how the revolution began, with seeing the dollars. We’ve talked about this before in conversations, and I know you’ve been very public about the fact that you had the ability to direct the second one — if you wanted to do it — and you did not. But you’ve also talked about the fact that they never hired another woman to direct the rest of that franchise and also these other franchises — the young women franchises, as I call them. What does that feel like now to have started something that just didn’t take off for women directors?

CH: Yeah, I think people like Drew Barrymore wanted to direct the second one, lots of women are obviously beyond qualified and would have done a great job on that, on “Divergent,” on “The Hunger Games.” I mean, those books were written by women, the screenplays are written by women — many of them — all the other “Twilight” movies [are written by Melissa Rosenberg], so why not? It worked with the first “Twilight.” But nobody else was given that chance — recently, of course, it’s changed. Patty [Jenkins] and other people have broken through but why did it even take that long? Why did it take another eight years?

We still hear the same things: “Can a woman direct an action movie, a war movie?” Well, Kathryn Bigelow did “Hurt Locker.” Years before that, she did “Point Break.” People just don’t believe it, or it takes a while to get into their bones. We’ve had 2,000 years, 3,000 years of seeing mens faces on a coin — that’s the emperor, that’s the president, whatever. We don’t see women on our dollar bills, and we’re just used to men. It’s ingrained, their positions of authority.

W&H: Do you feel like it has changed, even though it’s been so hard? Do you feel optimistic now?

CH: Oh yeah, of course. Because just like you said, there’s already five movies that would have come out this year [such as “Mulan” from] Niki Caro. There’s Gina Prince-Bythewood showing that she can flex her muscles and do a kick-ass job [with “The Old Guard”]. So, we see a revolution happening and we just got to keep it going, keep the momentum.

W&H: I feel like you’re from the generation of women directors who were pioneers in this world that we’re living in now. You and your peers are the test cases in terms of breaking down barriers, challenging sexism, making some headway talking publicly for the first time about some of these issues. Because for so long, everybody had been silenced into submission, basically. Finally, women were saying this just doesn’t make a whole lot of sense, in terms of the whole masculinity of directing, and taking that back. Do you agree with that assessment, and do you feel that you and your cohort have had that impact to take us to that next level of redefining what a director could be?

CH: Yes, like the Geena Davis Institute [on Gender in Media] says, every time you see it, you believe that you could be that person. So we put, like you say, Emily Mortimer in this show as a scientist. People can visualize themselves doing these jobs.

I’ve had multiple people tell me they saw the little director’s notebook of “Twilight” that we made [“Twilight Director’s Notebook: The Story of How We Made the Movie”], and they saw that a woman directed it, and thought, “If she could direct, I could.” One woman that I met, from a little town in Ecuador, she saw that book, and then I met her at the Academy a year ago. She made a film that got screened at the Academy because she saw there was a woman there. So every time, you see one more example, another example, until it just becomes normal.

W&H: Agreed. You’ve been involved in the fight for gender equality through ReFrame, and any aspect that you could. Now there are men involved in it — we had Paul Feig last week on here. I just wanted to get a sense from you, is that work rewarding for you? Do you mentor young people? What pushes you to the next place?

CH: Yes, I think all that is rewarding, and any time I get to do a forum like this, or I get to do some test labs pretty much every year where we work with diverse filmmakers from all around the world. And of course, interns and then of course [the question is,] how do you put it in practice on your jobs, as much as you can? I did a TV show in Canada one time where I said I really want a first AD that’s a woman, and I want a set coordinator that’s a woman.

“I haven’t been in the trenches with any women, Catherine,” the boss would tell me — the producer — “but I know that you can really count on this guy.”

I’m like, “But how are you ever going to be in the trenches with a woman if you don’t give her the chance to go into the trenches?” So in that case, I got to hire a female first AD, she kicked ass, then the second I left after I did my two episodes, they fired her for no reason, and brought the guy in that he’d been in the trenches with. So she got two episodes — better than nothing, but…

On “Don’t Look Deeper,” we have a woman who is our composer, Nora Kroll-Rosenbaum.

W&H: Nora, she’s my friend!

CH: Isn’t she great?

W&H: I was texting with her. Nora Kroll-Rosenbaum — if anyone needs a composer, I will hook you up with her.

CH: She is so talented, like the female Trent Reznor, and she just does amazing things. You saw the show — it’s very subtle but she really wanted to bring up the humanity of the character, so you feel like the breath is an instrument. You hear breathing, you hear vocals.

We have a woman stunt coordinator, Heidi Moneymaker — that is her real name. We tried to get as many women involved, and people of color, so that we had a really beautiful, inclusive crew.

W&H: That’s great, and I think that’s the power that people have to use: hiring, because that’s how you make the change.

CH: And with those opportunities now they’ve got another cool thing on their resume. That helps you get the next job, and the next one.

W&H: I’ve got a couple of questions here for you that I’m going to just start asking: Do you stand when you are making a pitch in person, versus, I guess Zoom? Is it okay to do that?

CH: Well as you can see, I’m standing right now. For me, I do have a lot more energy standing, and actually when I’m directing on the set, I very rarely sit down — maybe one or two times during the day. We don’t really have a director’s chair for me. So I do feel more energized when I’m standing up but a lot of times that’s not that appropriate in a room [where] everybody is sitting down at a table. I will try to use an excuse, like jump up to a picture on the wall, but usually I try to not look like I’m towering over other people.

W&H: The next question is: What was your favorite part about working with Quibi? Was the creative process different?

CH: Yeah, it was cool because we were one of the first dramatic shows to shoot, right there in the beginning, so when I first met Quibi there was only like five employees. Actually, in this same room where I am right now, one of the main guys — the Chief Content Officer — came over. He was explaining to me about the turnstile [feature] — you have to do it in horizontal and vertical, and I was going to do a little testing.

So I said, “Well, maybe when [the character] dives under the table to pull out the plug, you can turn the phone sideways. Would you mind acting out the scene?” So he crawled under the table — this is like the head guy — because that’s how nimble, and young and energetic, and just open-minded they were. They were inventing the technology as we were doing the show, so that made it fun. We were trying to do something new, and we were one of the test cases with the horizontal or vertical [option].

W&H: And Quibi, the whole thing was supposed to be about people on the go with their phones on the subway, or whatever, and now nobody’s on the go anywhere. I watched all of the episodes on my computer, and that’s how I would guess people are watching it now if they’re not on the go. Is it turning? Is it switching?

CH: If you watch on your phone, you can turn it. I like that you’re almost getting to edit it yourself, you’re almost getting a close-up of Helena, so you feel like you’re on FaceTime.

W&H: That’s awesome. What are you most proud of in your work so far?

CH: Oh, well, I feel very lucky and a lot of gratitude — telling Nikki Reed’s story was pretty amazing. That she was able to share that story, “Thirteen” — she and I co-wrote it when she was 13 years old. The fact that that story went out around the world, and I’ve met so many women and girls that could see that story and feel like “that was my story too.” Not even just women — Skrillex told me he’d seen the movie like 25 times, he felt like he was an outsider. Margot Robbie told me she saw it in Australia and could relate to it. So the idea that people all over could relate to something, and it could help them through a tough time.

Then “Lords of Dogtown” was the same thing — these boys in very rough childhoods, rough family lives, but they found something creative to do with broken concrete and empty swimming pools. They actually created a whole art form, a whole sport out of it. So I love those things and people still get inspired by that movie.

“Twilight” people told me they learned how to read because they saw the movie. They were dyslexic, they went back and learned how to read, and they made friends around the world, people that felt very lonely — they created this beautiful community of people that were really excited about the book. So I’ve seen so many stories — it’s just so fun when it touches people in an unexpected way.

W&H: Yeah, that’s really gratifying. You directed the video for “Til It Happens to You” from “The Hunting Ground,” a very important documentary about rape on campuses. The song was performed by Lady Gaga, and nominated for an Oscar. Talk about how and why you got involved in that.

CH: The writer of that song is Diane Warren, 11-time Academy Award nominee. She’s a good friend of mine, and on multiple projects of mine she’s written a song for it. In fact, in “Don’t Look Deeper,” we use her song “If I Could Turn Back Time,” the Cher song.

W&H: She wrote that? Shit, I didn’t know that.

CH: Yes, and so I said, “Diane, I need to use ‘If I Could Turn Back Time’ for this flashback.” But we couldn’t afford Cher’s version of it, so we have an eight-year-old girl singing “If I Could Turn Back Time,” and that girl has pipes. She’s so good.

W&H: Release that as a single.

CH: I know, I’m trying to get Diane to put it out there. Nora produced it, so we’re going to have it on the soundtrack, or something. But it’s just so fun, in episode 10. It’s just weird to have this little girl singing Cher.

[On “Til It Happens to You,”] Diane said, “Catherine this is a very meaningful song to me.” And Diane, myself, and really everyone that worked on that video had had a similar experience, everybody has been through something like what’s spoken about in the song. So it was a very powerful day of shooting, people were just coming to me, everyone’s telling each other stories. Even the actors and the three men that I had cast — they were all friends of mine — to play the “attackers” as we call them, they felt so uncomfortable, freaked out doing this. It was just very intense and triggering but important to put the stories out there.

Each attack had a different scenario — one was a friend who is pushing the friendship too far, one was like a “hate rape” gender situation, and one is a date rape — roofies. These were some very common stories for college campuses.

W&H: Yeah. So, we’re still in a pandemic, we have been going through an uprising, a reckoning about race in our culture, and three years before, we had the #MeToo movement. There are a lot of things about this industry that have shifted, and I am sensing — I don’t know for sure, I don’t live out in LA — that things are changing. When things start up again, the systems that were so inequitable in so many ways, particularly on race, are just going to have to be different. People are just not going to accept it — people who are watching things, as well as people who are making things. Have you had conversations with people? Is this something that you really are focused on? I just want to get a sense of your feeling about what’s happening.

CH: Yes, I mean, of course these two issues have always been important to me — if you even go back and look at “Thirteen,” you’re going to see every character that could be diverse is — the teachers, the boyfriends, everyone — but still remaining true to Nikki’s story, of course. She grew up in a very diverse neighborhood, in Culver City.

I mentioned the movie “Three Kings.” I remember riding around in the van — if you’re on the production side, you ride around in vans a lot, looking at locations, and the producer will be up in the front on their phone, the director will be working on the script. I remember saying, “Hey, could the reporter be a woman?” And David did change the reporter to be a female reporter like a Christiane Amanpour, played by Nora Dunn. So by raising my hand in the back of the bus in the ’90s… I tried to get another one of the soldiers to be a woman, I brought pictures of soldiers — he didn’t go for that but at least I got one. So always, we have to keep raising our hands in the back of the bus, we have to keep trying. I think I got off topic but, yes, it’s always mattered to me in a big way.

W&H: So talking to your peers now, your representation, and other folks who are going to hopefully go back to work soon, how are people going to build in new systems so that they’re more equitable?

CH: Well, that’s what’s very interesting. On “Don’t Look Deeper,” we had an African-American actress and actor — Helena Howard and Don Cheadle — and I wanted to be sure that when they walked down the set, they did not see a white crew. I didn’t want to see a white crew. You do have to challenge the norm, like “Let’s go call the guilds, and ask them who are African-American makeup artists? Let’s make a big effort.”

You just can’t go back to the people that some people have hired multiple times — you have to give new people a chance, and work harder to find [people like] Heidi Moneymaker. She’s awesome, she had a lot of credits as a stuntwoman but not as a stunt coordinator. She was as professional and badass as any coordinator I’ve ever worked with that has 50 times the credits; she just hasn’t been given the chance.

W&H: Right. Talk to any woman and she’s had to work twice as hard to get half as far, and same thing for people of color. We got a couple more questions. What’s your dream project now? Who do you want to work with? What’s the dream of Catherine?

CH: Well, I dream that I can go back to the project we were doing because that whole cast was incredible, plus, I love the city of New Orleans — awesome, beautiful location. But I have projects that I’m writing, like the girls skateboard show. We went out and met all these awesome women that have found their tribe through skateboarding, and we met a bunch of girls in LA, and we’ve shaped the stories around them — so I really want to tell that story.

A new script that I’m writing — I’ll let you know, hopefully I get to make that. I like things about the environment, because even with all this crazy shit, we can’t forget about the environment!

W&H: Last question: What advice would you give to a woman director and/or writer starting out, who wants to be successful in the business?

CH: That’s an awesome question. There are so many cool things you can do, especially even right now. Obviously you can go online and watch all the masterclasses, and all these great creators that are doing behind-the-scenes and telling their stories about how they created shows. Of course you can grab your camera, or your iPhone and make your own stuff.

I thought this was an awesome book that Robert Rodríguez wrote a long time ago [“Rebel Without a Crew, or How a 23-Year-Old Filmmaker with $7,000 Became a Hollywood Player”]: he just says make it yourself, make a short film, edit it, put the music, put the credits, and show it to people. Listen to the criticism, and make another one right away, and make another one right away, and keep elevating your technique, your craft. So those are things that can happen instantly.

Then, of course, if you can be lucky like I was and you have another job that you can do, you can go work on other people’s films too, because I learned a hell of a lot by production designing and volunteering on other people’s sets on the weekends. Then you can see how other people work.

Mostly it’s get your skillset up, know your shit — so that when you go in there, or you get that chance, you’re gonna make it great. So you’ll get to the next one, and the next one.

https://youtu.be/jOXSUGLSk1o