People prefer gossip, conspiracy, or drama over truth

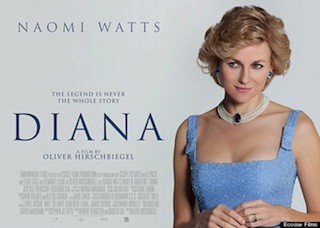

because we’re cynical. The recent release Diana

about the final years of Diana Spencer, Princess of Wales, is a controversial

attempt at rendering a portrait for the screen. The film is based on extensive research beginning with journalist/author

Kate Snell’s book Diana: Her Last

Love, interviews, news archives and Diana’s personal letters. From this

position, director Oliver Hirschbiegel, actors Naomi Watts and Naveen Andrews and screenwriter

Stephen Jeffreys create a lush and dystopian love story between a British royal

and a Pakistani heart surgeon.

In a haunting opening scene moments before the tragic

accident on August 31, 1997, the camera lingers behind and around Diana (a captivating

Naomi Watts) without capturing her face. As the film proceeds, temporarily eluding her death,

the camera trains on Diana’s countenance at a public event as if to reacquaint

the audience with a familiar face. Princess Diana, as some may recall, had an emotive

manner that endeared her to the public as a relatable royal. Furthermore, her

youth, style of dress, divorce and humanitarian work gave her unprecedented

celebrity status, especially in the press.

These early scenes in Diana advance

quickly with abrupt shifts in sound design to elicit feelings of dislocation or

disconnection. In this respect, we experience the icon, but soon experience

Diana’s life as a divorcee on a spiritual journey.

Like The Iron Lady, Diana is

caught in the wake of a public figure with an emotionally charged image.

Indeed, as much as Diana, Princess of Wales was a coveted figure, she was

largely unknown. The film shows that Diana was often the mastermind

behind her public statements and some well-placed tabloid stories meant to

counteract her troubles, promote a humanitarian mission and satiate popular

demand. Though The Iron Lady couldn’t manage Thatcher’s bulky contentious image, Diana juggles iconic image and reality

with greater skill by focusing on a specific time frame and many small intimate

accounts. In fact, personal narratives from friend Simone Simmons (Juliet

Stevenson) and spiritual advisor Oonagh Toffolo (Geraldine James) feature in

the film, providing insight into Diana — a complex, strategic, seductive

and deeply sensitive woman.

After

Oonagh’s husband, Joseph, falls ill, Diana meets Hasnat Khan, his doctor. According to an interview from Oonagh, Diana was

smitten from the start and began to pursue the doctor while finalizing her

divorce. These scenes are full of the schmaltzy lines. At one point, while getting acquainted, Hasnat responds to a

question about surgery and says “You don’t perform the operation,

the operation performs you.” There are many such lines in the film that

seem like hackneyed poetry; as in a later scene in bed with Hasnat quoting

Rumi. However, I wonder if these foibles serve a purpose. It seems Jeffreys was

grasping for poetry. In fact, the entire cast and crew were grasping for poetry. The cinematography of warm tones,

blues and greens all elicit romance. But one important point to make is how often do we see a love story

with a professional Pakistani man and royal British woman? And how receptive

would we be even if the lines were perfect?

The scene that made the greatest impression on me was with Hasnat’s

mother, Naheed (Usha Khan), whom Diana meets when she travels to Pakistan to meet his relatives. Khan’s mother is a stunning, educated woman who pointedly

holds Great Britain accountable for its colonial legacy in Pakistan. Naheed’s

first words to Diana express her political beliefs and leave Diana speechless. Yet Diana is able to shake this off and manages to acquaint herself with less critical

family members and soon is frolicking among the children like a long lost aunt. But the script gets in its own way again by fumbling for poetry — Aha! ‘The people’s princess!’

Fundamentally, Diana is

a flawed, melodramatic romance. Its greatest appeal is not in a

dystopian love story, but in Diana’s journey to find herself through

spirituality, love and profession. Although the love between Diana Spencer and

Hasnat Khan seemed genuine, it’s unfortunate that Diana’s life consistently

relates to the cliché of a princess finding her prince charming. Clearly there

is no such thing. Such is to say, the image

of Diana Princess of Wales as a woman searching for romantic love overshadows

the reality of a woman in search of herself. The film attempts to illustrate this

point without explicit mention, but may have done better under a woman’s

direction.

Like Hirschbiegel’s exceptional historical feature Downfall, about Hitler’s

last days, Diana demands suspension

of disbelief. The audience must believe in the life of a princess, star-crossed

romance, and the tyranny of the press. However, Diana, like the princess, is up against a cynical world and as dismal box office returns indicate, for most, suspension

of disbelief for an well known woman and an unfamiliar love story is too much to ask.