Naked

limbs, tangled, dancing; gaping mouths; and sightless eyes — much of Iranian

artist Bahman Mohassess’ work strikes the first-time viewer alternately as a

celebration of the human body — and a testament to human suffering. Dubbed “the

Persian Picasso” in the West, Mohassess was once the doyen of the Iranian art

world, yet his work was the victim of censorship after the Revolution. One of

his most high-profile sculptures was even given paper underwear to protect its

modesty. It was later “accidentally” destroyed. Incensed by the turn the cultural atmosphere

in Tehran had taken, Mohassess left the city for good, but not before

destroying the bulk of his remaining work in a final, tragic act of defiance.

Painter

and filmmaker Mitra Farahani’s documentary Fifi

Howls from Happiness (which opens in New York on August 8 and

in LA on the 15th) is named for the one painting Mohassess could never bear to part with. The film begins with the director tracing Mohassess to a

hotel room in Rome, though she coyly refuses to tell us how she managed to

track the reclusive artist down. Her decision not to detail her search for

Mohassess is well-judged, for it allows the man himself to take center stage in

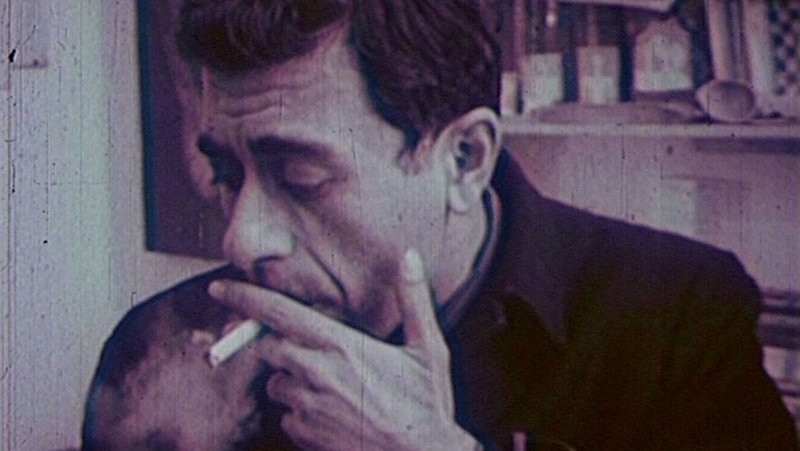

all his cackling, cantankerous, and complex glory. Cigarette in hand — and an oxygen

tank at his side — an embittered Mohassess promises to tell his life story, “so

that every idiot doesn’t purport to write my biography the way it suits him.”

The resultant film bears scant resemblance to a biography, but is at once something

more delicate — and powerful. As the ailing artist embarks upon one final

commission, Farahani juxtaposes his railing against “immortality and all that

rubbish” with his need to leave something for posterity in her own work — even

to the point of dictating elements of the documentary’s visuals and voiceover — in what becomes a poignant meditation on the importance of artistic freedom and

cultural inheritance.

Farahani, who now lives in Paris, is no stranger to the kind of scrutiny that made Mohassess’ existence in Iran impossible. Her 2004 documentary Taboos, which dealt with issues

surrounding sexual desire in Iranian society, was filmed clandestinely in the country, and she was arrested and

held in prison on returning to Tehran in 2009 in the wake of Iran’s disputed

presidential election.

Women and Hollywood spoke with Farahani about Mohassess,

his art, and how the “ignorance” which Mohassess blamed for the destruction

of his oeuvre continues to haunt the Iran of today.

WaH:

What initially drew you to Bahman Mohassess and his work, and made you decide

to seek him out?

MF:

The story of Bahman Mohassess was known to most Iranians who at least have

heard about art and literature. It’s not his symbolic importance,

acknowledgement, or fame that was lacking, but his physical presence. He would

always be referred to rather as a myth or a living legend than an actually

existing person. Mohassess’ works function in such a way that his fishes [a

recurrent image in the artist’s work] and still lifes are looking out there to

the world, a cynical and crude look. Thus the “creator” of such “creatures”

should embody such a look to the world himself. I wanted to find the

disappeared body behind this very peculiar look.

WaH:

In the film, Mohassess describes the destruction of his work as “the victory

of the ignorance of these times.” Was part of your motivation in investigating

the fate of Mohassess a desire to highlight the fact that that ignorance still

reigns victorious today?

MF:

Certainly. Do you have any doubts about it?

WaH:

Do you entirely share Mohassess’ disillusionment with the lot of the artist

(especially the female artist) in Iran, or are you optimistic for

cultural change?

MF:

Not optimistic at all. What I share with him the most is the belief that the

issue of power is not bound to power per

se, but often depends on the people themselves, to what extent they

unconsciously encourage this power and its structures.

WaH:

There are several moments in the film where your relationship with the audience

is very playful — your refusal to tell us how you tracked Mohassess to his hotel

room in Rome, for example. Is it important to you to make your directorial

presence felt in this way in all your work, or was this just a conscious

imitation of Mohassess’ own impish personality?

MF:

I feel there was no other way for the film to eventually exist, than having

Mohassess’ constant recommendations and “film directions” integrated and put

forward. Not only because it “allowed” me to do this impossible film on an

impossible character reflecting on his potentially impossible chef d’oeuvre. But mainly because

Mohassess was a man of power, at every stage of his life, embodying,

counterbalancing, addressing or fighting power.

Therefore, I was certainly not

surprised, and I praised those instructions as part of the process. They were

revealing to me. I discovered that I would never do “my” film on someone’s life.

I was only helping the last chapter of an already begun movie, to become

archived and visible, a movie begun long ago, without me. The movie of the

collective ignorance, which leads us to forget and dismiss our greatest spirits,

a movie in which Bahman Mohassess was the main protagonist (giving his film

instructions).

WaH: This is your second documentary portrait

of an Iranian modern artist of note (Farahani interviewed pioneering female

artist Behjat Sadr in 2006 for Behjat

Sadr: Time Suspended). Is this something you wish to continue doing? Where

do you see your film work going in the future?

MF:

I’m not likely to do another film specifically on “someone,” though art history

remains a constant interest and resource for me.

WaH:

Have you any advice for aspiring female filmmakers?

MF: 1. Since a camera is something too heavy for women and initially made for men,

you need a good cameraman.

2. Never give advice to women about how to behave or

work because they are shrewd enough already.

3. Never seek financial

independence in independent cinema since independent cinema doesn’t make money.