Diedie Weng grew up in Guangdong, Southern China and is currently based in Lausanne, Switzerland. Weng received her MFA in documentary production at the State University of New York at Buffalo. She has previously directed several short documentary projects, including “Mosuo Song Journey,” “Building on the Past for Our Future,” and “Ming Day and Night.” “The Beekeeper and his Son” is Weng’s first feature documentary.

“The Beekeeper and his Son” will premiere at the 2016 DOC NYC film festival on November 13.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

DW: The film is the story of a beekeeper and his family, which I shot while I was living in a village in Northern China. I followed the family for over a year, during which time the young son, Maofu, came home from the city to learn beekeeping from his father, the old beekeeper Lao Yu. This gave them a chance to work and live with each other, but their different ideas about the future of the bee farm led to conflicts, and they struggled to communicate. Meanwhile, their bee colonies were going through a crisis, which added even more stress but also brought the two characters together.

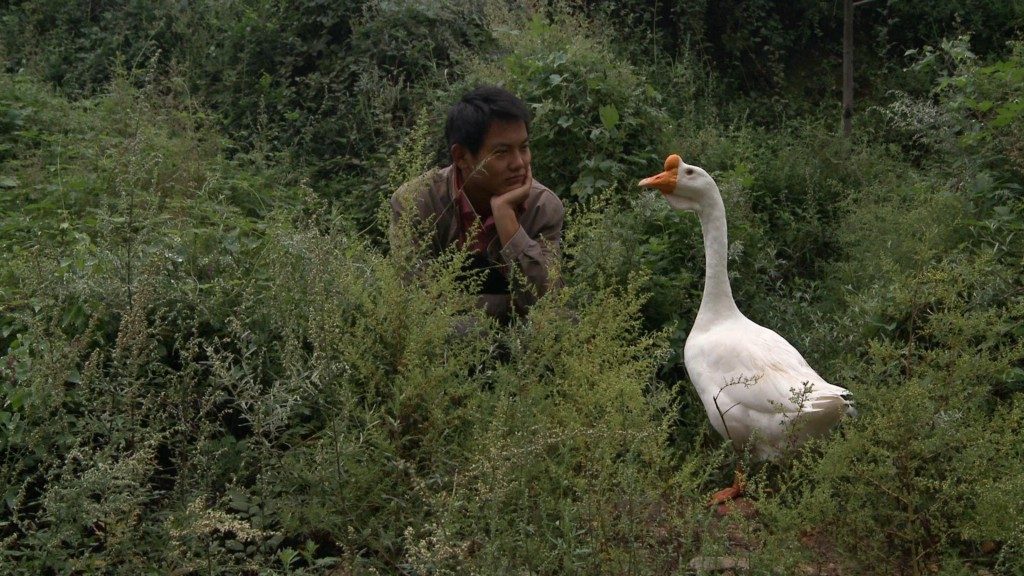

All the while, there was a bossy goose, who loves both the son and the father. He went his own ways with both characters and managed to keep the film together with his humor.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

DW: I was interested in the beekeeper’s traditional beekeeping craft and the situation of the bees in rural China facing environmental stress. Even though the father really expected the son to focus on beekeeping, the son showed more interest in selling and marketing honey than in beekeeping. As the two struggled with their communication, the center of the film shifted to a father and son relationship story. This change also opened me up to the delicate challenges in understanding and capturing the emotional needs and conflicts within and between characters.

In some ways, I felt a strong connection with the son, since I was also struggling with the search for my own identity between worlds, and attempting to communicate with my own parents, who have a totally different life and different expectations.

Alongside the family story, the activities of the bees took on a metaphorical meaning. I was intrigued by filming the parallel cycles of life in both the bee hives and the beekeeper’s family, as well as the survival stress they share under environmental degradation. At the end of the movie, the fleeing of the bees resonates with a son whose heart kept wandering away from the bee farm.

W&H: What do you want people to think about when they are leaving the theater?

DW: I hope the film will give people a sensual feeling of the beekeeper’s home environment in China, and an intimate experience of their family life with its ups and downs, sweetness and bitterness. I hope the film can reach the audience to the point that they feel a connection with their own life and their own issues.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

DW: During the filming, I captured very strong emotional scenes. In these moments, the characters may not always come across as very sympathetic. And sometimes they retreated to their own corners for quiet moments. It was often a very delicate choice where to position the camera, and when to film. Instead of provoking the characters with my questions, I waited for them to open up to me and invite me inside their space instead. I also held myself from acting as a judge in their family conflicts and instead tried to show the full complexity of the characters.

I was very nervous when the family was watching the first rough cut, but it turned out that the family identified with the film and liked it. The father said, “This is a family, you know. We fight a lot: ups and downs.”

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

DW: I first spent 15 months researching and filming in the village by myself. I then shared some footage with Vadim Jendreyko from Mira Film, who liked my material and mentored me until the first rough cut [was finished]. At that stage, the Mira Film team decided to take over the production. Susanne Guggenberger took up the main producer role for the film with courage and love. We presented part of the rough cut to funders and Swiss TV, who supported the film.

W&H: What does it mean for you to have your film play at DOC NYC?

DW: We are very excited to present the film in such a progressive and prestigious festival as DOC NYC. I am curious how families in New York will connect with the father and son story. I am also curious about the urban beekeeping scene here, and how the film will find its resonance with local beekeepers.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

DW: Trust your own inner voice, trust the depth of life and the moments, and stay present during the filming. And take the time it needs to finish the film; don’t rush it for festival submission deadlines or your other plans. For me, these count as the best [pieces of] advice. It’s always easier to remember the good advice than the bad.

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

DW: I became a mother in the middle of the editing of this film. For years I have [delayed becoming] a mom because of the fear of losing my mobility, time, and creative freedom. But, as a mom, I felt a new growth and softness inside me, which enriched the final film. I still need to figure out how to continue to make new works with a young child, but I have never regretted my choice.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

DW: I recently watched quite a few films directed by the Japanese filmmaker Naomi Kawase. I am intrigued by how she followed her personal life quests in her fiction works, and created organic and poetic parallels between local nature drama and human life stories. At this point of my life, constantly moving between worlds, I also envy and admire that she always makes her work in her hometown.