Kimi Takesue is an award-winning filmmaker and the recipient of the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship in Film. Takesue’s critically acclaimed Ugandan feature-length documentary “Where Are You Taking Me?” was commissioned by the International Film Festival Rotterdam and premiered at the festival. Takesue’s films have screened at more than two hundred film festivals and museums internationally, including Sundance, New Directors/ New Films (MoMA & Lincoln Center), Locarno, Rotterdam, SXSW, and the Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art. She is an Associate Professor in the Department of Arts, Culture, and Media at Rutgers University-Newark.

“95 And 6 To Go” will premiere at the 2016 DOC NYC film festival on November 12.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

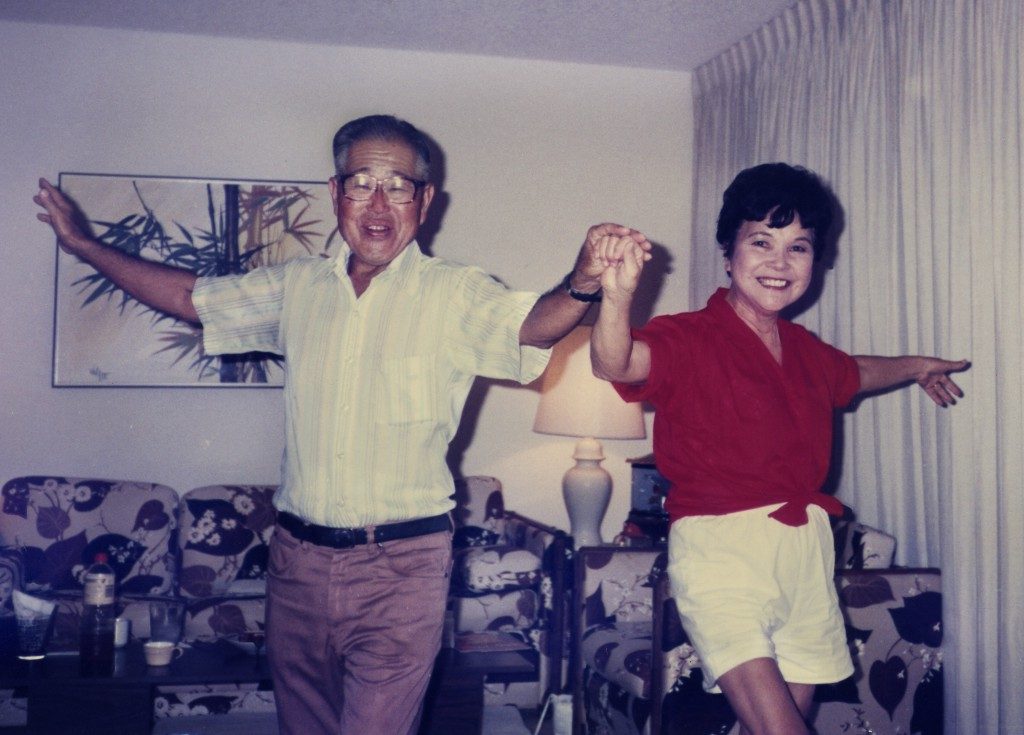

KT: “95 And 6 To Go” is a complex portrait of my resilient grandfather, a retired postal worker, who lived in Honolulu, Hawai’i for nearly a century. As I capture the cadences of his daily life — coupon clipping, rigging an improvised barbecue, lighting firecrackers on the New Year — Grandpa Tom shares his life story of immigration, love, loss, and endurance.

Unexpectedly, he becomes intrigued by my stalled fictional screenplay and offers advice that is as shrewd as it is surprising. My fictional love story — and Grandpa Tom’s creative revisions — serve as a vehicle for his past memories of love and loss to surface.

Shot over six years in Honolulu, “95 And 6 To Go” is an intimate meditation on absence and family and expands the notion of the “home movie” to consider how history is accumulated in the everyday and how sparks of humor and creativity can animate an ordinary life.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

KT: While growing up in Hawai’i, I never knew my Japanese American grandfather, Tom Takesue, harbored creative interests. I never saw him read a novel or talk about art. For me, he existed on the fringes; he was a pragmatic, hard-working, authoritarian grandfather who consistently reinforced the importance of family obligation and a steady job.

When I was at the peak of development on my first feature film project, a cross-cultural love story, I was shocked when my grandfather became intrigued with the screenplay. While slurping noodles or munching on toast, he offered suggestions about a catchy title and happy ending.

In 2007, after the death of my grandmother, I returned to Hawai’i to provide support and assistance. My grandfather was far from sentimental about her death, already keen to find a new companion. The optimism surrounding my feature film project had faded as I waited for the producers to secure financing. My grandfather expressed his fear of dying alone.

We were both in periods of transition and emotional loss. During this time, we finally came to know one another; I offered him company and he offered advice on my film project. His frank critiques reflected his concerns about love, aging, and the recent death of his wife. He also shared personal stories of a life filled with loss and regret, in stark contrast to his romantic and idealized suggestions for my screenplay.

Life and artistic paths are typically filled with digressions and setbacks but sometimes lead to unanticipated discoveries. “95 And 6 To Go” explores personal and creative loss and how loss is countered with perseverance. It is a film about unrealized ambitions and the ways we respond to disappointments.

“95 And 6 To Go” is also a film about an unlikely artistic collaboration between a granddaughter and grandfather and how an inter-generational bond is forged through art.

W&H: What do you want people to think about when they are leaving the theater?

KT: I strive for a contemplative form of cinema that, ultimately, asks the viewer to reflect on content, structure, and the overall immersive experience of the film. I try and create work that has multiple points of entry and can be appreciated on conceptual, emotional, and aesthetic levels.

“95 And 6 To Go” raises many issues around family, aging, memory, loss, untapped creativity, and inter-generational connection, but it is also a piece that asks viewers to consider film structure, visual rhythm, and the poetic possibilities of non-fiction cinema.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

KT: “95 And 6 To Go”is an intimate and personal film. Initially my grandfather objected to the footage being shown to the outside world so I thought I was only collecting material for myself. In many ways, he was a resistant subject, and I had to shoot with restrictions, though in the end, he gave permission for the film to be made.

Another big challenge I faced was the larger, unknown question of whether a personal film would be of interest to, and resonate with, an audience. The film had its world premiere at Doclisboa film festival in Lisbon, Portugal and it was extremely satisfying to see the film connect with audiences cross-culturally.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

KT: “95 And 6 To Go” is a low-budget film that is primarily self-financed. Overall, I was quite self-sufficient and directed, produced, shot, and edited the film. I received some small grants in the latter stages of post-production.

The film is also, in part, about a fiction project that never was realized, but which received grant funding from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation. I ended up allocating some of the Guggenheim money toward “95 And 6 To Go” since a “new” manifestation of the project had emerged.

W&H: What does it mean for you to have your film play at DOC NYC?

KT: It’s a wonderful honor to screen at DOC NYC among such a strong lineup of films. “95 And 6 To Go” was 11 years in-the-making and much of that time was spent in isolated circumstances. It’s inspiring to finally share my film with audiences and fellow filmmakers and to connect with a larger community of documentary makers.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

KT: It’s essential to stay true to one’s vision and to set your own standards of success. In the end, you as the filmmaker need to be proud and pleased with the film you have made. The worst advice is to believe that you have to conform and produce films in one rigid way.

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

KT: It’s essential to persevere and not overthink it all. At the end of the day, it’s all about the work that is produced. It’s important to identify what is unique about your perspective and what you have to contribute to the mix.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

KT: Over the years, I have been inspired by many women filmmakers including Lynne Ramsey, Heddy Honigmann, Trinh T. Minh-ha, Claire Denis, and Chantal Akerman because they bring intelligence, originality, and poetry to their films which always linger after viewing.

W&H: Have you seen opportunities for women filmmakers increase over the last year due to the increased attention paid to the issue? If someone asked you what you thought needed to be done to get women more opportunities to direct, what would be your answer?

KT: Women are directing films. They may not be directing many large budget films, but they are directing films, and we need to consider the quality of the films being made rather than assessing everything in relation to the size of the budgets.

In terms of future opportunity, it is essential for women to support one another, and this is happening in more organized ways through groups like Brown Girls Doc Mafia, Asian American Women Media Makers, and Film Fatales; these groups are creating community among women filmmakers by sharing knowledge, resources, skills, and creative ideas.