Sally Jean Williams has produced and directed for the National Geographic Channel, Lifetime and Animal Planet/Discovery Networks. She worked with award winning global production house NHNZ filming orangutans in Borneo, dinosaur fossils in China, and rockets at Space X in Los Angeles. Since 2010 Williams has been directing short form projects for non-profits and private biographical films for selected clients through her company Salient Films LLC. “Ken Dewey — This Is A Test” is Williams’ first feature length documentary.

“Ken Dewey — This Is A Test” will premiere at the 2016 DOC NYC film festival on November 12.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

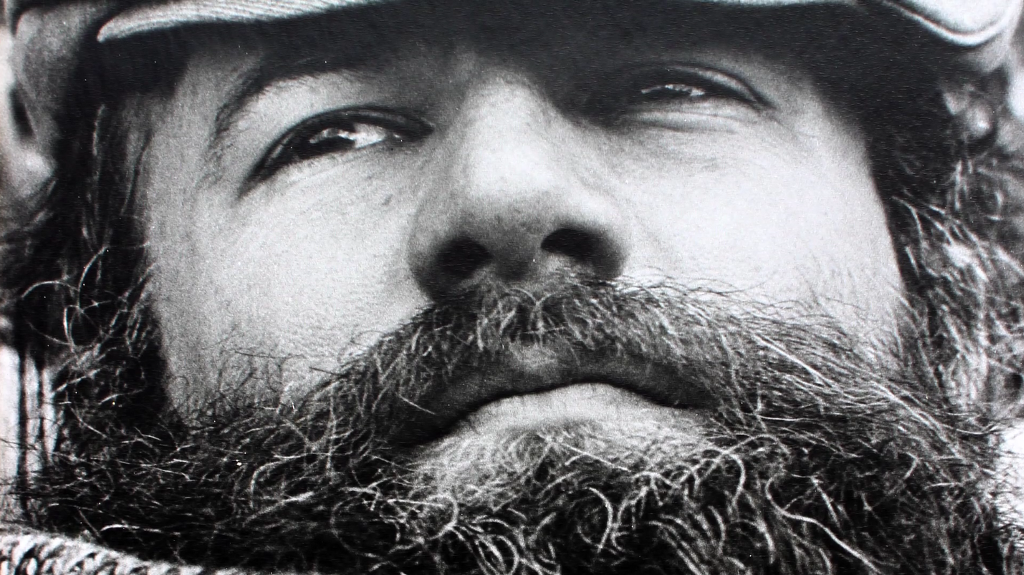

SJW: “Ken Dewey — This Is A Test” is a 90 minute biographical feature about the unheralded yet pivotal artist Ken Dewey. Dewey was a visionary performance artists in the ’60s and ’70s and a pioneering force during the formative years of the New York State Council on the Arts.

Whether at the 1965 Selma civil rights marches, the courtrooms of Scotland, or the attempted deportation of John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Dewey’s quest to express the highest of human ideals through art helped shape a generation. His quest was cut short by tragedy.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

SJW: I think the definitive moment came when I was sitting in the Schomburg Center For Research In Black Culture listening to archive recordings that Dewey had made while he participated in the Selma to Montgomery marches in 1965. The recordings were visceral, horrifying, delicate, kind, thoughtful, and seemingly made without ego or position. In many ways it was what Dewey didn’t say that drew me to tell his story. The goosebumps made me do it.

Also the dedication from his family to have his story told four decades after his death. They knew Dewey’s papers, films, and audio recordings were precious and they did everything in their power to protect them — including donating the collection to the New York Public Library. Thanks to Dewey’s family his story was protected and the stories of those he collaborated with: Allen Ginsberg, James Baldwin, Yoko Ono, John Lennon, Don McLean, Odetta, and Terry Riley, to name a few.

W&H: What do you want people to think about when they are leaving the theater?

SJW: Maybe more than anything I’d just like them to experience the film and pay attention to what they feel. I do know how that sounds, but Dewey stood for something much bigger than himself and to oversimplify that would be a disservice.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

SJW: Finding Ken Dewey. It has been 44 years since Ken was on this planet. Despite the huge abundance of audio, which took one year to digitize, Ken had this intolerable habit of not making everything about himself. He was so about the other that he almost disappeared in his audio recordings — it took listening to all 600 recordings to find what is in the final film.

His written work was different. He definitely reveals more of himself in his writing but I wanted people to hear from Ken and experience him, [and] not [via]a graphic or someone reading his words. Also Ken’s moving image archive was only partially digitized and I couldn’t access as much as I hoped so I went global and found archive in the U.K., Finland, and Sweden.

At one point I scrolled through every newsreel of John Lennon and Yoko Ono on the Associated Press website in the hope I might catch Ken standing in shot..I was mildly delirious, but it did pay off.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

SJW: Ken’s family deserve all the credit for getting the film funded. It was one of those rare birds that involved private funding and came to me funded.

W&H: What does it mean for you to have your film play at DOC NYC?

SJW: I was ecstatic to get into DOC NYC. I had heard only good things from friends who had shown at DOC NYC and I thought it could be a great fit for “Ken Dewey — This Is A Test.” We hoped for a New York premiere because many of Ken’s friends and collaborators live close by and we wanted them to experience the film first.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

SJW: Best advice: Feel the fear and do it anyway.

Worst advice: I was once told by a boss to “go and get on a plane” after asking that I be paid the same as my male counterpart. That was bad, ugly advice, which I duly ignored. The happy ending is that the very same person, who I now deeply respect, became one of my biggest champions. I think if something ugly happens, sometimes it is worth giving that situation a chance to change — if it doesn’t change, consider the plane.

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

SJW: Build strong networks — with men, women — whomever. People that both have your back and get your vision are a rare breed so grab on with both hands. Also, try to help others get where they are going. I’d give the same advice to men.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

SJW: “The Piano” by Jane Campion. Everyone went bananas for that film in New Zealand when it came out in 1993. I was 13 years old and clueless. We had Helen Clark as our Prime Minister at that time so basically I felt like, “Well of course Campion made a critically acclaimed film — a woman is running the country — this is what men and women do.”

Thanks to Jane and Helen my impressionable pubescent synapses were bathed in equality and I had absolutely no idea what that meant until much later. Campion had absolutely busted through a heavy door for women in film and television in New Zealand and beyond. Gaylene Preston, Robin Laing, Catherine Fitzgerald, and Judith Curran are other heroic kiwi filmmakers who I very much look up to.

W&H: Have you seen opportunities for women filmmakers increase over the last year due to the increased attention paid to the issue? If someone asked you what you thought needed to be done to get women more opportunities to direct, what would be your answer?

SJW: I think the fact that 44 percent of films at DOC NYC were directed by women is a really progressive achievement. I think change comes very, very slowly, and we have many women and men from decades past to thank for any progress happening now. As for what could be done to give women more opportunities to direct, I’d say to bathe young synapses in equality.