Abigail Child has been at the forefront of experimental writing and media since the 1980s, having completed more than 50 film/video works and installations, and written six books. Her most recent work is an ongoing trilogy of feature films, including “Unbound,” an imaginary “home movie” of the life of “Frankenstein” author Mary Shelley, and “Acts & Intermissions,” on the life of anarchist Emma Goldman in America. The trilogy’s final installment is “Origin of the Species.”

“Origin of the Species” is screening at the 2020 DOC NYC film festival, which is taking place online from November 11-19.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

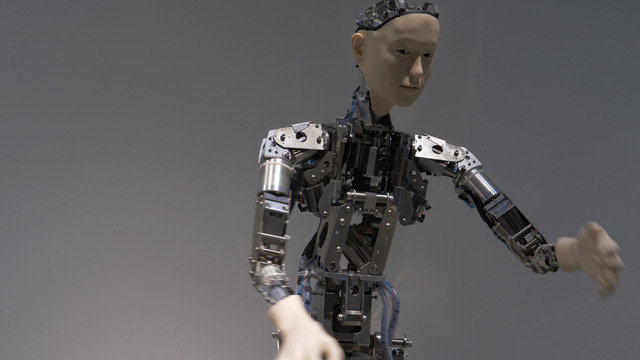

AC: Weaving historical and pop culture mythology with cutting edge robotic research in both Japan and the United States, “Origin of the Species” inventively foregrounds our future in the present: how we are already living in a world of science fiction, in respect to our biology, transport, architecture, behavior, and communication. The result is a compelling, uncanny, and sometimes intense exploration of the human dream to reconstruct a “body” — to create a mechanical life-form.

We are led on this journey by the android BINA48 (Breakthrough Intelligence via Neural Architecture), who is modeled after a Black lesbian and designed to test hypotheses concerning the ability to download a person’s consciousness into a non-biological or nanotech body. Personable and occasionally humorous, BINA48 is alternately hopeful, analytical, and naive.

The film foregrounds a necessary female perspective, and humor, asking: How do subjectivities and nationalities shape our imaginings of an “appropriate” mechanical companion? Why are Siri and Alexa “fitted” with female voices? Are robots to be pets or primates, companions or soldiers, toys or ghouls?

The last in my trilogy of female desire, “Origin of the Species” reveals the contemporary dance between metal and flesh, as humans become more mechanical — with bio replacements and dependence on computers and phones — while robots, those human mirrors, aim for consciousness.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

AC: What could be more important right now than our relation to machines? We are already fully participant, while the final results on our society, our bodies, our minds, remain unknown. Artificial intelligence decides what we watch on Netflix while algorithms on Facebook infect our politics. Data is drawn from us every minute we are on the web, walking down the street, talking on the phone. There’s a big push right now to build increasingly sophisticated AI. With innovations in prosthetics and household units, AI is already changing the way people live their lives. It’s easy to imagine a future where robots and people routinely live together in households. Sex robots are being built and introduced into society: what will this do to human intimacy?

This project places us close to the scientists who create these future machines. Some keep the human in the loop. Others create metal containers for bodies they feel are potentially replaceable: newscasters, receptionists, companions, sexual partners. The list is startling. Are we imagining that androids will inherit a world we poison? Is this contemporary research connected to our unconscious desire to populate a world that we have made hostile to human life?

“Origin of the Species” is the last of my trilogy on women and desire, and the content has come full circle. The first film, “Unbound,” recreated the life of Mary Shelley, teenage author of arguably the first sci-fi novel, in the form of imaginary home movies, shot in contemporary Rome. In the second film, “Acts & Intermissions,” I examine the life of Emma Goldman and anarchism in the early 20th century where many of her struggles — for equality, immigration, and contraception, and against police brutality — echo in the present. I knew I wanted a virtual woman as my 21st century heroine in “Origin of the Species.”

My cultural influences include Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein,” Philip K. Dick stories, and automata such as the fortune-telling humanoid of the amusement arcades at the Jersey Shore when I was growing up. Equally so, the cartoons I watched with obsessive affection. The result is an abiding interest in artificial construction, how it is created, and how our society will use/or enslave it.

W&H: What do you want people to think about after they watch the film?

AC: I want my audience to question their own relation to machines and what the future may bring. How do we feel watching the current limits of the machines we keep on improving? What does it teach us about being human? What do we make of a group of scientists engineering machines and algorithms to create new life? And how do different countries relate to these machines? How will our social experience change when interactive humanoid entities are as ubiquitous as smart phones? How will we respond to their humanoid, fashionable, possibly erotic, shapes? How will they play into human emotions and instincts for bonding, for violence? How will androids challenge our moral and ethical instincts? Will they make war in our place? Who will write their software personalities? Do they and AI really pose “our greatest existential threat”? We want to bring these questions into public consciousness in a way that brings us face to face with this fundamentally disruptive technology.

As well, there is a mythical component. Robotics raise many issues of the artificial, the human, and the threshold between these, as well as the boundaries between the inanimate and the animate, the souled and the un- or non-soul, the present and the future, the real and the imagination. The idea of a creature that might “imitate” a person has long existed in human myth and story. Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” suggests those desires and fears, as do earlier incarnations of the Golem. Robots and androids, as well as implants and cyborgs, bring the future of an artificial human closer to reality. They suggest that the virtual is merging with the human, the simulation is spreading to the real. These developments reflect the future as present, as our dreams become engineered fact.

That the actual process — conception, manufacture, and use — is often hidden makes the project that much more important and intriguing. Our aim is to promote thinking and a discussion that is timely, intelligent, humorous, and cautionary.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

AC: Obtaining the first grant — from the Asian Cultural Council — which allowed for travel to Japan. We had begun to shoot at Tufts University’s Human-Robot Interaction Lab in Massachusetts and already knew we needed to go to Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka to get the full story.

The other challenge — as always — was the issue of how to structure the film. This involved many months of editing, trying various combinations of scenes, getting lost, and finding the structure. The result usually ends up close to what we imagine at the beginning, but you don’t always know how to get there. You are not following a plan; you are inventing a structure and have to figure out how to construct it!

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

AC: It’s an independent feature. We received the first grant from the Asian Cultural Council after several years of searching for funds, and used that money to travel. Then we made a 23-minute cut that enabled us to submit for other private and government grants, federal and state. In the end, we received production and post-production funds from the LEF Foundation based in Cambridge, Massachusetts; from the New York State Council on the Arts; and ultimately, the welcome New York City Women’s Fund media grant, administered by the New York Foundation for the Arts.

We applied to many more places where we didn’t win any funding. We were persistent and lucky.

W&H: What inspired you to become a filmmaker?

AC: I was in my last year at graduate school and received a small grant, maybe $600, to make my first film, shooting 16mm in New York City. I was editing at an advertising house after 9 p.m., working the red-eye shift through to the next morning. One night, I had an epiphany: that film brought together all my interests — in music, language, movement, image, history, and anthropology. I loved the interaction of these disciplines and that I could play with them. This fascination has never wavered. I feel as challenged, as excited, as awed in front of cinema’s multi-vorticular flow and its potential for entwined rhythm and content now as I did then.

At the time I thought I would be an anthropological filmmaker in South America since my undergraduate minor was in anthropology and I spoke Spanish. In some ways, I think of myself as an anthropologist of the contemporary, with a particular interest in the body.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

AC: Best advice: When you don’t know what to do with the edit, when you’ve been working and it’s not working — at least not to your liking — a fellow filmmaker advised, “There is always something to do. Start on that and inevitably, other ideas will pop into your head and you will be onto the work.”

Worst advice: “No one will look at this unless Gwyneth Paltrow is starring.”

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

AC: Don’t be discouraged. Be persistent. Believe in yourself, or no one will.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

AC: There’s too many, but let’s pick Claire Denis’ “Beau Travail.” Denis and her camerawoman, Agnès Godard, film the French Foreign Legion — strong men peeling potatoes and hanging laundry — with a plot loosely based on “Billy Budd.” The soldiers are both “feminized” and jealous of the beauty of a newcomer. Closely observed and attentive to the body and landscape, the film pinpoints the outside-ness of the soldiers to the Africa in which it is set, Djibouti. It closes with a crazed, exquisite dance that expresses the anger and frustration of its anti-hero hero.

[I’m selecting this film to discuss] for its subtlety, its humor, and its transgressions in terms of character and plot. Nothing runs linear in Denis’ films. They start and stop with emotional bias and visual splendor.

W&H: How are you adjusting to life during the COVID-19 pandemic? Are you keeping creative, and if so, how?

AC: I finished “Origin of the Species,” so yes. And earlier in the spring, I completed “Blue Edit,” a short that I had started a year or so before, in the midst of the feature. Sometimes I need a break; films take a long time and it helps to back off and come back, that complicated dance with one’s art.

I also have been doing collages, which I make intermittently, and writing with a bunch of friends for a poetry tea and a poetry simultaneous walk, where we are stretched across the globe walking together and writing about it.

I am, however, yes indeed, missing so many of my friends. Zoom helps but is not the same, to say the least. I hope to start a new film, or at least begin to organize footage I have gathered for it. Surely I will need more material but it will help me weather the upcoming months.

W&H: Recent protests in the U.S. and abroad have highlighted racism and anti-Black police brutality. The film industry has a long history of underrepresenting people of color onscreen and behind the scenes and reinforcing — and creating — negative stereotypes. What actions do you think need to be taken to make Hollywood and/or the doc world more inclusive?

AC: Many things, of course! We need less stereotyping and more people of color onscreen — and definitely in a wider range of roles. I used to disparagingly note that even when Black actors appeared in major movies, they would often — inevitably — die, if not first, then before the film’s conclusion. Clint Eastwood’s “Unforgiven” with Morgan Freeman comes to mind.

We also need more women and people of color directors, camera folk, and editors. More power needs to given to so-called “minorities” at the top of the power pyramid.

As an artist, I always think of Charles Burnett when he was working on his feature after “Killer of Sheep.” The set designer would come to him to ask if he liked this or that chair and he felt there were too many choices that took him away from the creative task of making the film. What I am saying here is that projects need not always get larger, but rather wider — more voices, more styles, more genres, more representative of the people we are.