Jamie Boyle is a two-time Emmy-winning documentary filmmaker. She is the director, cinematographer, and editor of the short documentary “Take A Vote” and she is the producer, editor, and cinematographer for Emmy Award-winning documentary “Jackson.” She edited “Trans in America: Texas Strong,” and served as an associate editor as well as production manager on the Emmy nominated “E-Team,” which won the 2014 Sundance Cinematography Award. She was the in-house editor for the American Civil Liberties Union and Human Rights Watch and has also taught at the Bronx Documentary Center, as well as served as a judge for the News & Documentary Emmy Awards.

“Anonymous Sister” starts screening at the 2021 DOC NYC Film Festival on November 11. The fest runs from November 10-28.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

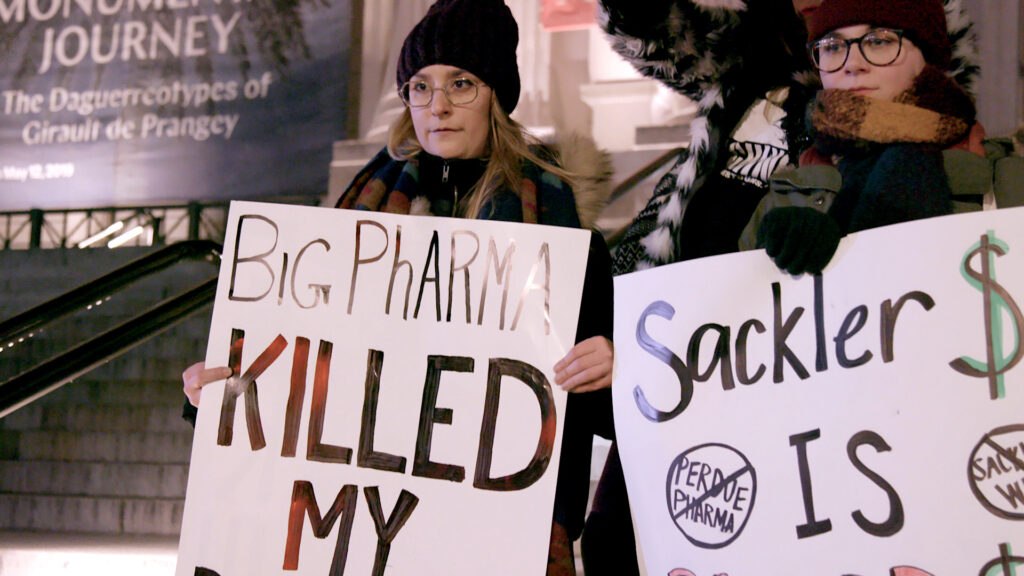

JB: Years before I heard the term “opioid epidemic,” I watched my sister and mom succumb to an unknown, unnamed illness. I began filming as a way to understand what was happening to them and as a last-ditch effort to rescue them from its clutches.

Thirteen years later and with both of them sober, I set out to finish what I’d started. “Anonymous Sister” is a memoir that chronicles our lives before, during, and after my family members battled debilitating addictions at the hands of their doctors.

Woven throughout our narrative are the people and events that sunk the entire country into the same state of despair and resulted in the deadliest man-made epidemic in U.S. history.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

JB: This isn’t actually a story that I was drawn to but one I was pulled into unwillingly. The film opens with the quote, “The camera makes you forget you’re there. It gives you both a point of connection and a point of separation.” That’s what the camera did for me and what allowed me to tell this particular story. There are things that prove excruciating to look at, especially too closely, but willful blindness or ignorance will only perpetuate it. The camera offered me a way to look at something I couldn’t bear to otherwise. It was with me on my darkest days, suspending time, and holding them alive for one more moment.

There are a lot of films that deal with various aspects of the opioid epidemic, but what I felt was missing was the view from inside a family dealing with it. I’d argue this is one of the most important vantage points from which to talk about this topic. I was still a teenager when my family was going through it, but I remember thinking that if the decision makers, the people in positions of power, and the medical community at large were watching it happen in their family, to their sister, their mother, we wouldn’t have a problem. So I started filming as an effort to let people into my family, to see what I was seeing as I was seeing it, and this was before I understood what I was looking at.

That footage was the first I’d ever shot. A decade into a career in filmmaking, I decided to pick it back up. Not only was I witnessing new dangers to my sister and mom’s hard-won sobriety, but the nationwide problem was growing dramatically worse every year and the attention never seemed to be in the right place— on the unfathomable prescribing rates of opioids in this country.

While this epidemic has taken on many forms, most recently the high rates of heroin and illicit fentanyl use and overdose, what started the problem and what remains at its root, is the legal prescribing of opioids for conditions, doses, and time periods, that they should never be prescribed for. This is still happening and new cases of substance use disorder are being created at the hands of our most trusted professionals. This is where all the other issues stem from and this is what the film examines and exposes.

W&H: What do you want people to think about after they watch the film?

JB: I hope people think about what it is that they cherish and whether the systems that ostensibly exist to protect us are serving any such purpose. I want people to think about their own vulnerabilities— the people and things they care about most, then reflect on what it means to live in a society where those are preyed upon and seen as opportunities for profit. I hope it leads them to think about what that must mean for the most vulnerable, the most marginalized, and whether they are okay with upholding the systems that enable and reinforce such a society.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

JB: Because I was so young and had almost no filmmaking experience when I documented my mom and sister’s addictions, we had limited coverage of the most pivotal years of the story, about an hour of audio recordings and thirty minutes of Super 8 film. But it was because of this that we chose a more experiential approach— finding unconventional ways to place the viewer in the mind of the subject and go through the story with them. It also sent us digging up hundreds of hours of home movies and recording new footage of the present-day realities of our lives. Both of those allowed us to do what so few films on the topic are able to, which is reveal the entirety of the people at its center and show who we were and what our lives looked like before and in the aftermath.

The other thing that proved challenging for me as a filmmaker and as a person was trying to do justice to four different people’s realities and memories, my own included. I wrestled with this on a constant basis and I’m still wrestling with it. It took two full re-edits of the film and an incredible team of filmmakers to figure out how to unravel this family saga and do it in a way that felt as truthful as possible for everyone involved.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

JB: “Anonymous Sister” was funded by a combination of grants, donations, and investments. Our greatest support came from individuals who were personally invested in or impacted by the opioid epidemic who were eager to see a more personal account of the issue.

We had the honor of being invited to the Sundance Catalyst Lab & Talent Forum in 2019 where we met investors and donors who were interested in the issue and looking for independent work to support. We also received incredible support from Vulcan Productions, Sundance Institute, IDA, Fork Films, NYSCA, and others.

W&H: What inspired you to become a filmmaker?

JB: This story and experience is what inspired me to become a filmmaker. When all of this began, I had just started an Introduction to Film course in college but hadn’t yet chosen film as a major, let alone a career path. I realized very quickly the power of the camera and all that it could be–– a witness, a weapon, a hiding place, a mirror. There are few other objects or methods that would allow a 19-year-old to defend herself against the most powerful and corrupt forces on earth.

Even if it did take many years for that footage to reach the public, it undoubtedly saved me and I believe it played a role in my sister and mom being alive today. What could be more influential on a young person’s life? After that experience, I would have melded a camera to my shoulder if I could. It took me a while to begin to comprehend the full weight and responsibility of that, but I’ve been a steadfast believer in the potency of filmmaking ever since.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

JB: That’s hard to narrow down. For best advice, I’ll go with this. I worked retail at the mall when I was 15 and complained one day to my mom how tedious and upsetting I found it. My mom, who was no stranger to manual or demeaning labor, said, ”Well, I know how you feel because I felt the same way. And you’re probably always going to feel that way about working a 9-5 job that you despise, but you have to earn a living. So you’re going to need to figure out very soon how to make money doing something else.” I’m unfathomably privileged to have so far been able to do that.

I’m not sure what the worst advice I’ve received was. Hopefully the fact that I didn’t commit it to memory means I didn’t listen to it!

W&H: What advice do you have for other women directors?

JB: Look to other women for help and help other women in turn. Insist on relationships, teams, and communities that lift you up and hold you there. Walk away from the ones that don’t. Don’t shy away from being decisive or aggressive, but demand that your male-identifying counterparts exercise and exhibit traits historically associated with womanhood: compassion, care, patience, selflessness, respect, and regard for others.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

JB: Only one? “Persepolis,” directed by Marjane Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud. I saw it in my early 20s and it gave me so many things in one fell swoop. It showed me a new way of thinking about what it meant to be a woman in the world. It gave me a playbook for resisting harmful forces, but also laid bare the horrifying cost of doing so, especially for the most marginalized people on the globe.

It was a reminder at an extremely impressionable age that as a white woman born in one of the richest countries in the world, I was obligated to use those privileges to try to help provide a platform and power to the underrepresented and unheard.

W&H: How are you adjusting to life during the COVID-19 pandemic? Are you keeping creative, and if so, how?

JB: It changes from day-to-day. Editing this film during the pandemic was a blessing and a curse. It allowed me to continue working and providing for myself and my family. The fact that I was also able to continue doing what I love most was a gift beyond comprehension.

The blatant and intentional spread of misinformation which has led to the horrific loss of life from COVID-19 is eerily reminiscent of what started and continues to perpetuate the opioid epidemic. It made for some difficult days in the edit room.

Many of my family members are still afraid to get the COVID-19 vaccine and many continued with daily life and gatherings when the virus was at its worst. It was surreal trying to navigate that reality while spending all day with footage from the last national public health crisis that came so close to destroying my family with misinformation. Some days I dove in wholeheartedly, and others I could barely do anything. As much as I was able to, I let myself have those days.

W&H: The film industry has a long history of underrepresenting people of color onscreen and behind the scenes and reinforcing — and creating — negative stereotypes. What actions do you think need to be taken to make the doc world more inclusive?

JB: I look to women of color to direct me on what actions need to be taken to begin remedying these historical and ever-present inequities and misrepresentations. I have immense admiration and respect for the work being done by Carla Gutierrez and others on the BIPOC Editors Database— connecting BIPOC editors at all career levels with production teams and implementing fundamental changes to combat underrepresentation.

I’m also a big proponent of the slogan “Nothing about us without us.” Initially used as a rallying cry for disability rights activists, it has become a mantra for all underrepresented communities. I’ve come to understand how that isn’t something we just aim for but have to insist upon.