It seems like everyone’s talking about women right now. With the 2012 presidential election just a day away with a demographic breakdown of male to female voters at 48% to 52%, women’s voices are more important than ever in American election history, and both parties are courting women aggressively.

In fact, things SEEM to be looking up everywhere for women — even in film & television. Since 2010, when Kathryn Bigelow was the first female to win the Best Director Oscar, the news media abound with articles about how women directors are gaining credibilty.

But it simply isn’t true. While celebrations are wonderful, they may lead women to a false sense of confidence. Recent statistics clearly show that there are NOT more women in film and television. And while Kathryn Bigelow is indeed an inspiration to all directors, male and female, she cannot solve the disparity problem.

Media is America’s most influential global export, but in terms of film and television content, it comes almost exclusively from the perspectives of male directors. The ratios are staggering: according to recent DGA statistics, 95% of feature films are directed by men, and just 5% by women. Episodic TV is nearly as bad, with the male-to-female ratio of working directors at 86% to 14%.

If women are not directing film and television content, it means half of the voices of the American population are silenced and half the visions are suppressed. Ending discrimination against women directors is vital to establishing a society of equality and diversity of perspective. It is not just the validity of the female point of view around the world and basic fairness that gives this issue such immediacy, but if we as a nation are to maintain a moral upper hand in geopolitical affairs, we must at the very least obey our own laws protecting equality.

As former DGA President Martha Coolidge recently said of directors: “For guys competition is fierce, but for women you are more likely to win the lottery.”Why is the gender gap among film and television directors so gaping and so blatant, and why does gender disparity remain static year after year?

The studios and the Directors Guild have been very busy in the past 30 years paying lip service to the need for more women directors, but lip service is all they have paid. While nearly every other industry in the United States has been making dramatic strides toward gender parity, the entertainment industry power players have been fundamentally negligent of this effort.

As a result, today’s Hollywood is often regarded as America’s most visible industry-wide bastion of discrimination against women. Changing that could help alter global perceptions of all social, economic, and geopolitical concerns, and not least of all images of women and girls. Initiating this change, however, will require that the DGA join forces with the studios to create equality for women directors.

Unfortunately, there seems to be an institutional bias within the DGA that prevents effective movement toward parity for women. For instance, in the 1980’s the DGA filed a discrimination class-action lawsuit against three major studios on behalf of their women (and minority) director members. However, the guild was denied class certification on the grounds that some of its own policies put it in conflict with the very interests of the women plaintiffs who had initiated the complaint in the first place. Judge Pamela Rymer postponed DGA classification in the case, stalling the lawsuit indefinitely.

Therefore, because of entrenched policies within the DGA itself, the guild was not allowed to proceed with the case. While the suit could not continue, the fact that the DGA initiated the legal action at all resulted in a dramatic positive change to the employment landscape for women and minority directors. In 1979, women director’s employment comprised a minute percentage of the male-to-female ration, yet thanks to the lawsuit, that number grew to almost 16% female employment by the mid nineties.

The change did not last, however. In the wake of that hindered legal effort, the guild and the studios made a joint promise, not to employ more women directors, but to use “Good Faith Efforts” to try to increase their employment numbers. The three words, “Good Faith Efforts,” along with a complete lack of goals and timetables, rang the death knell to hopes for parity for women directors.

So now thirty years later, the playing field for women directors has returned to a near-vertical tilt. A simple examination and evaluation of the prevailing DGA-studio approaches to increasing job opportunities for women directors clearly reveals why they have failed. To fulfill those “Good Faith Efforts,” they instituted diversity programs intended to fulfill their promise.

Over the years, the DGA, in conjunction with the studios, has experimented with a variety of TV studio directing fellowships to help its women (and minority members) — with mixed results. In fact, the programs have been widely acknowledged to be completely ineffective in budging the numbers of women directors at all.

The few studios that do anything at all for diversity directors are to be roundly commended. However, while the Disney/ABC-DGA Directing Program launched in 2001 boasts “one of the longest-running programs of its kind in the entertainment industry,” completion of the program by the selected fellows has resulted in relatively few actual directing jobs for its participants. Equally disappointing results have emerged for those who have completed the HBO-DGA Television Directing Fellowship Program.

Why do the DGA-studio directing fellowships fail to deliver significant results? The DGA is a craft guild and since the Middle Ages trades have used guilds to provide apprenticeships. Skilled, experienced artisans handed down expertise to the next generation in a wide variety of professions from the arts to banking. When we analyze the success of mentorships throughout history, what emerges as a key-contributing factor is the presence of reciprocity and mutual benefit.

In this light, we may begin to understand one reason for the overall ineffectiveness of the DGA-studio diversity fellowships. These programs are intended to engender mentorships between young talent and experienced directors and/or executives, and hopefully result in jobs. Unfortunately, they mostly serve to provide the DGA and the studios the mutual benefit of good publicity, rather than helping the women who participate.

While these fellowship programs have little to offer their participants, they are highly competitive, selecting the best of the best after a rigorous application process that takes months to complete. Winners enter the program with high expectations, and those who don’t make it feel crushed.

One woman recipient of the ABC/DGA Fellowship, who was already an accomplished director, spoke of her experience: “The DGA-ABC fellowship was a complete waste of time. On the sets, they stare at you like you’re a homeless person or a spy or a freak. The executives running the program as well as other producers don’t want the shows to hire the people in the (fellowship) program.

From the standpoint of studio employees who must tolerate these unwanted shadows, the selected fellows are little more than a nuisance who provide no opportunity for reciprocity at all. Since the relationship is not mutual, the reluctantly participating executives and TV crews often seem to look upon the female fellows as interlopers.

If TV director mentorship programs designed for women are to be successful, they need to include a policy of guaranteeing the mentee a directing assignment on a show after the observation period is completed. Since the fellowship application process is so rigorous, it is safe to assume that anyone who at last receives the venerated position would likely be adequately qualified to helm a show at the conclusion of the program.

The DGA diversity program, however, continues to promote these prestigious fellowships as progressive joint efforts forged by the guild and the studios to remedy the under-employment of its women and minority members. ABC and HBO, from their sides, continue to call the programs a success. And indeed, the programs are a wonderful boon to the maintenance of reciprocal good will between the DGA and the studios. But they do not help increase employment opportunities for women DGA members.

The fact is that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits employment discrimination based on sex. Discrimination against women in the film industry is against the law in the United States of America.

Both the DGA and the studios have explicitly repeated their commitment to solving the problem of gender disparity. Yet the DGA, which is the primary negotiating entity for all directors, is not demanding parity standards for women directors so in effect they are acting in collusion with the studios to maintain discriminatory policies.

The DGA must use every effective means possible to help institute new events, programs, and policies that really do change the playing field. We need to move beyond “good faith efforts” — which apparently are not good enough. We need to move on to “Best Efforts.”

Producers and executives need to exercise personal aesthetic decisions based on subjective criteria, but as we have seen, visible and invisible discrimination continually interfere with perceptions of merit where women are concerned. To inform this argument, it is useful to recall a famous quote from one of Great Britain’s foremost art critics, Brian Sewell, in the “The Independent” in 2008:

“The art market is not sexist. The likes of Bridget Riley and Louise Bourgeois are of the second and third rank. There has never been a first-rank woman artist. Only men are capable of aesthetic greatness. Women make up 50 per cent or more of classes at art school. Yet they fade away in their late 20s or 30s. Maybe it’s something to do with bearing children.”

Conscious or unconscious, this misogynist perspective is equally applicable to many executive decision-makers in the profession of film and TV directing. Therefore, one can easily see why some form of affirmative action for women in the entertainment industry may be extremely important in working toward parity. The fruits of affirmative action programs in the United States throughout the decades, from the 1950’s on, are paying off for many American minorities today, even though they were intensely controversial in their time.

Within the European Commission right now (The New York Times 10–23–12), there is a powerful effort being made to force gender parity within European companies. Currently, there is a proposal up for approval that would mandate that a 40% minimum of women be included on corporate boards of directors. This proposal comes with sanctions and penalties for violations in the case that corporations fail to comply.

This new effort is so controversial it is actually splitting the European Union, and it may not pass, but it is a striking indication of the direction that the world is going in terms of pressing forward for gender parity in all industries and professions.

The DGA points its finger at the studios, and the studios point their fingers at the DGA. Each shifts the blame to the other, and each responds with indignation to the suggestion that nothing is actually being done. The over-riding sentiment seems to be that everyone is simply flummoxed by the problem. A longtime DGA Executive VP recently wrote to me: “I hope you are successful where we were stupefied by our inability to move the issue forward. The legal complexities are stultifying.”

Stupefied? Stultifying? Is this really an insoluble conundrum? Or is it verbal obfuscation to maintain the status quo? While the responsibility of gender parity among directors ultimately falls to America’s film studios and other producing entities that actually do the hiring, the organization that must initiate crucial change is the Directors Guild of America.

Back in 1979, the DGA picked up the baton from six courageous DGA women directors, and led the charge for equality by initiating intense negotiations and finally legal action with the studios. If that action 30 years ago so effectively resulted in the brief, but triumphant move from ½ of 1% to 16% in employment rates for women directors, a second class-action lawsuit today (no matter how far it got) could push the numbers well above 30%.

Looked at from this point of view, the immediate future could be very auspicious and exciting for women directors. Furthermore, the DGA is fortunate to have Jay Roth, originally a civil rights lawyer, as national executive director. He is one of the finest negotiators in the industry and Daily Variety called him the “showbiz point person on making a deal to ensure Hollywood’s labor peace.”

Roth has successfully led negotiations on the guild’s major collective bargaining agreements six times since becoming national executive director in 1995. If ever there was a maverick to cut through the legal tangles and lead this industry to gender party through negotiations with studios, Jay Roth is the one.

THE TIME HAS COME…

For the leaders of the entertainment industry to play catch-up with almost every other sector of American society and even the playing field for women directors — once and for all.

_____________________________________

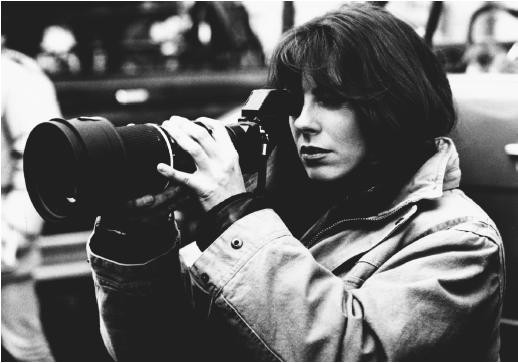

Maria Giese is an American feature film director, a member of the Directors Guild of America, and an activist for parity for women directors in Hollywood. She writes and lectures about the under-representation of women filmmakers in the United States. Check out WomenDirectorsinHollywood.