Guest Post by J.E. Smyth

Current debates in the media about women’s employment, representation, and visibility in Hollywood focus — perhaps predictably — on stars’ pay and the number of active female directors. Yet there’s also a sense that, however unequal the situation is now, things must have been far worse for women working in the film industry sixty, seventy, or eighty years ago under the studio system — and that women should be grateful for some small improvements.

How very far from the truth this is.

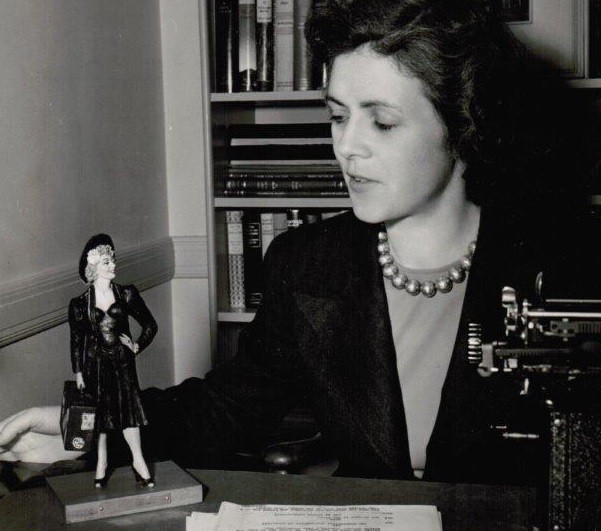

In 1942, the year Bette Davis and Katharine Hepburn earned higher salaries than President Roosevelt, the Screen Writers Guild elected a new president — Mary C. McCall Jr. She would be elected three times (1942–43, 1943–44, 1951–52), and for two decades was one of the most articulate and powerful advocates for screenwriters and their union. Before McCall came on the scene and helped broker the first contract with the producers, it was well known up and down Hollywood that the average writer made less per week than a secretary.

McCall worked to get the screenwriting profession its first minimum wage, unemployment compensation, minimum flat-price deals, maximum working hours, credit arbitration, and pay raises during WWII.

She specialized in films about women and was proud of it. She was less happy working at Warner Bros. In 1936, on loan out to Columbia, she was on the set every day working with director Dorothy Arzner, star Rosalind Russell, and editor Viola Lawrence on “Craig’s Wife.” It was Arzner who persuaded her to fight the misogynist atmosphere at Warner Bros. and commit to a serious career as a writer.

Two years later, she moved to MGM and crafted the sleeper hit of the year, “Maisie.” Ann Sothern’s never-say-die working woman became a cultural phenomenon and was one of the industry’s most successful franchises. During the war, McCall headed the Hollywood branch of the War Activities Committee, the Committee of Hollywood Guild and Unions, and the Screen Writers Guild.

But, being Hollywood’s top organization woman was only one part of her life. At the height of her career, she had and raised four children with two different husbands. She famously gave birth to twins 24 hours after her last story conference on 1935’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” She was a firm believer in the Equal Rights Amendment, and a lifelong Roosevelt Democrat. Hollywood producers destroyed her career when she stood up against Howard Hughes and RKO pictures when they denied Communist writer Paul Jarrico credit on “The Las Vegas Story” during the blacklist.

You won’t find any of this in academic or popular histories of Hollywood. These days, she’s all but forgotten, while Dalton Trumbo and the other male Hollywood Ten are remembered and even get biopic makeovers.

Things are changing.

On March 16, the Writers Guild Foundation will be honoring McCall’s life and legacy with a 35mm screening of “Craig’s Wife” — which is still not available to the public on DVD — and “Reward Unlimited,” a 10-minute documentary short she wrote about women’s war work which hasn’t been screened since 1944. After the screenings, McCall’s daughters, television writer Mary-David Sheiner and former Los Angeles Times film critic Sheila Benson, will sit down with me to discuss McCall’s career. The reception and event, held at the WGA theatre in Beverly Hills, are free.

When McCall came to Hollywood in the 1930s, women’s membership in the Screen Writers Guild hovered between 20 and 25 percent and was nearer a third during the war. But membership plunged for women in the 1960s down to the teens and shrunk further in the ’80s and ’90s. Since the millennium, numbers have slowly increased. Now, 24.9 percent of women are film guild members, but far fewer women writers are being hired for major productions now than the norm seventy or eighty years ago.

Why should we remember Mary C. McCall Jr.? Because she believed in women’s careers; because she believed in the importance of a union; because negotiation, compromise, and political moderation made her and her profession powerful. She is a role model to be reckoned with. And she proved two other things: that Hollywood’s women could call the shots in their careers and that seventy-five years ago, a woman could be president…

J. E. Smyth is Professor of History at the University of Warwick (UK) and the author of several books on American cinema, including “Edna Ferber’s Hollywood” and the BFI Classics volume on “From Here to Eternity.” Her book on Hollywood’s many high-powered career women — starring Mary McCall — will be published later this year by Oxford University Press.