Irene Taylor Brodsky is an Oscar-nominated, Emmy and Peabody Award-winning director whose documentaries have shown theatrically, at film festivals and on

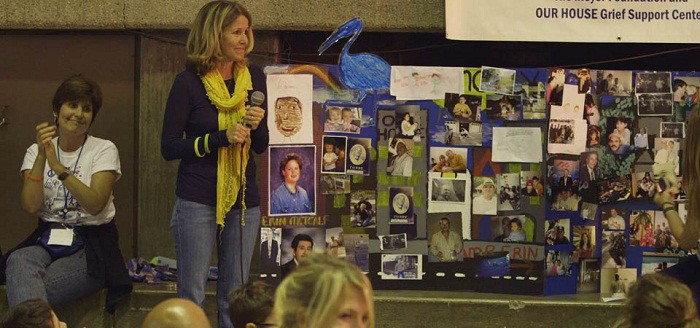

television worldwide. Irene most recently completed One Last Hug (and a few smooches): Three Days at Grief Camp, a short film exploring how children

grieve.

In 2011, she completed the Emmy-winning Saving Pelican 895 for HBO Documentary Films, following the life of a single bird rescued from the

2010 Gulf Oil Spill. For her 2009 short-subject film The Final Inch, she was nominated for a 2009 Academy Award, three Emmys, and won the

International Documentary Association’s Pare Lorentz Award for cinematic excellence. In 2007, Irene turned the camera on her own family to make her first

feature-length documentary Hear and Now, which won the Sundance Film Festival Audience Award, and went on to receive numerous Audience and Jury awards

around the world, a 2008 Peabody Award, and a nomination for Documentary of the Year by the Producer’s Guild of America.

One Last Hug (and a few smooches): Three Days at Grief Camp

is playing at HIFF as part of the Documentary Shorts program.

Women and Hollywood: Please give us your description of the film playing.

Irene Taylor Brodsky: This short film is about how children grieve and deal with death. We filmed a weekend-long “grief camp” for kids as young as 7. Some

lost a parent to illness, and others to violence or suicide. It’s staggering to see so much heartache in one place, but this community of children and

professionals are really able to help each other.

WaH: What drew you to this story?

ITB: I have three sons, and I was so relieved to learn that “grief camps” even exist. About 10% of kids will lose a parent before they leave home. I

personally did not, but I know so many who did. The anguish is still there. I knew it was an important subject, and I wanted to help let families know that

there are places like Camp Erin to go for help.

WaH: What was the biggest challenge?

ITB: When interviewing these grieving children, I had to take them to a very uncomfortable place. There was a professional grief counselor by my side when

we filmed one-on-one, which reassured everyone, especially me.

WaH: What advice do you have for other female directors?

ITB: Know the camera. Shoot when you can. Don’t let anyone make you think you can’t.

WaH: What’s the biggest misconception about you and your work?

ITB: With documentaries, people too often assume you’re drawn to your subjects through personal experience or expertise. With the exception of Hear and Now — a memoir about my deaf parents — I’ve always taken on my film subjects cold. Entering the unknown is the best part of this kind

of non-fiction filmmaking.

WaH: Do you have any thoughts on what are the biggest challenges and/or opportunities for the future with the changing distribution mechanisms for films?

ITB: Yes, there are many more distribution platforms for doc filmmakers (and our relatively small audiences) but I’m not yet convinced of their actual

value. And I’m frankly exhausted trying to vet them all. Are niche audiences in a world of so much aesthetic clutter a good thing, or are we just preaching

to the choir? Ideally, I’d like to keep making films and leave the creative alchemy of distribution up to those I can trust.

WaH: Name your favorite women directed film and why.

ITB: I’ll just mention my favorite of this last year: Stories We Tell. I’d call Sarah Polley’s tone — whether she’s directing narratives or this

doc — picture perfect.