Mia Donovan is an award-winning filmmaker based in Montreal. She was the recipient of the prestigious Don Haig Award for outstanding achievement as an emerging filmmaker in 2012. Her films have been presented worldwide at film festivals, on TV broadcasts, theatrically, and on digital platforms such as Netflix. In 2016, Donovan wrote and directed her first virtual reality experience, “Deprogrammed VR” which won the IDFA DocLab Award for Digital Storytelling that year.

“Dope is Death” was scheduled to screen at the 2020 Hot Docs Canadian International Film Festival. A digital version of the fest has been organized due to the COVID-19 pandemic. “Dope is Death” will screen in Hot Docs Festival Online, which will launch May 28 and is geo-blocked to Ontario, Canada. More information about the program and how to tune in can be found here.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

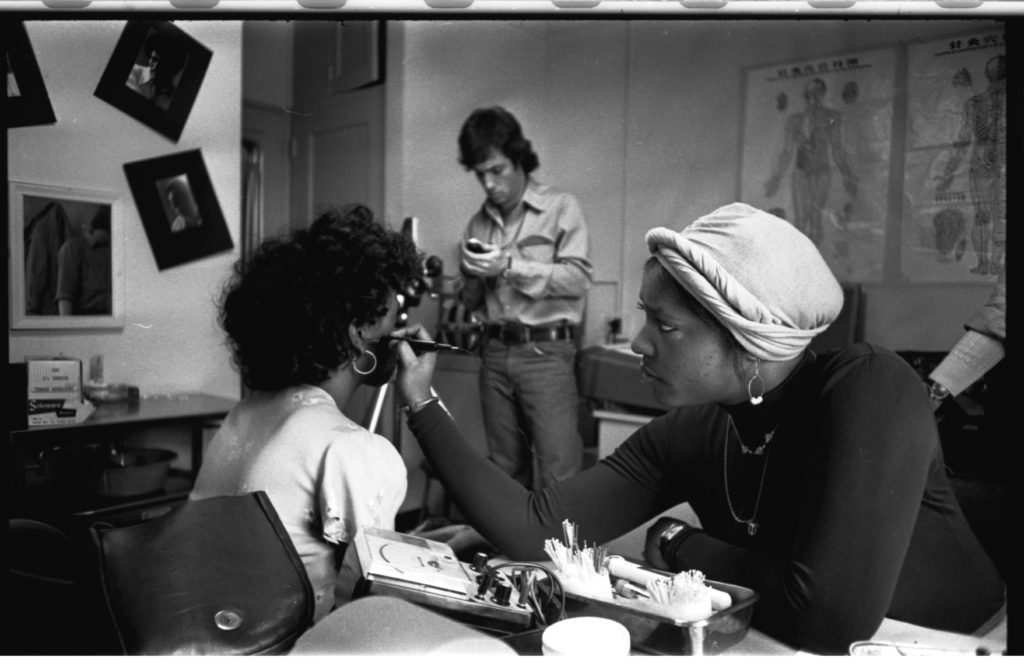

MD: “Dope is Death” traces the radical roots of acupuncture in America to the Black Panther Party and the Young Lords. It’s an inspiring documentary about a collective of young radicals — mostly in their late teens and early 20s — who took over a dilapidated hospital in the South Bronx to provide essential healthcare to their people, and to develop a holistic drug treatment program called the Lincoln Detox.

Ear acupuncture is now being used worldwide to treat drug addiction, trauma, and anxiety — but most people don’t know where this treatment modality comes from. It was born in one of the poorest neighbourhoods in America during the early 1970s in direct response to Nixon’s “war on drugs.”

W&H: What drew you to this story?

MD: I was so drawn to this story from the first moment I heard about it. We first met Mario Wexu about eight or nine years ago. He is the Montreal based acupuncturist who taught the activists from the Lincoln Detox back in the mid-1970s, and got them certified in acupuncture. I can’t explain why, but this story just really touched me, and when I started to research this history I found very little information.

So I started writing to Dr. Mutulu Shakur, Tupac Shakur’s stepfather, who has been incarcerated since 1986, and then I started visiting him in prison around 2014. He was a member of the Republic of New Afrika and became the political director of Lincoln Detox in when he was 21 years old, and was the first to really advocate for acupuncture as an alternative to methadone maintenance — the addiction pharmaceutical treatment for heroin.

W&H: What do you want people to think about after they watch the film?

MD: I want people to really consider the large scale ramifications of the war on drugs and its role in criminalizing a population. We need to question why there has been a shift in compassion towards drug dependency in recent years with the advent of opioid addiction, which has not only been caused by the pharmaceutical companies, but is largely associated with suburban white America.

I hope people will leave this film with more insight into how politicized and political healthcare has become.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

MD: The biggest challenge was to build a story around a protagonist we could not record or film at all. Dr. Mutulu Shakur has been incarcerated in maximum security prison since 1986, and there have only been a handful of interviews done with him behind bars during the 1990s.

It was important to me to represent Dr. Mutulu Shakur as the heart of this story, without falling into the tropes of a hagiographic biopic.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

MD: The financing for the film was done in Canada. It was done with some broadcast money, some public equity money, and a lot of sweat equity!

The major issue was the fact that Dr. Sjakur was never released from prison, so we had to find a way to purchase a lot of archive and work around that roadblock, which extended the timeline massively and put a lot of stress on the team. We’re really happy it’s done.

W&H: What inspired you to become a filmmaker?

MD: In 2004, I saw a young woman named Lara Roxx on the local news in Montreal. She had just tested HIV positive after working in Los Angeles as a porn star, and I was shocked at how the news was representing her tragedy as trivial. I reached out to Lara, because at that time I was working on a series of photographic portraits of sex workers, and I wanted to photograph her.

She confided in me that she felt exploited by the mainstream news coverage, which sensationalised her story, and that she really wanted someone to do a real documentary about the porn industry. It took six years, but we made “Inside Lara Roxx” together, and that collaboration changed my life.

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

MD: My advice to documentary filmmakers is be ready to make a lifetime commitment to your subjects. It’s a huge responsibility and privilege to have anyone trust you to tell their story, and you should remain mindful of this during every step of the process.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

MD: It’s hard to limit this answer to one film, but I will highlight Chantal Akerman’s 1975 masterpiece “Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles” as one of the first films I saw that I recognized as a distinct and powerful reflection of women’s bodies in cinema.

In contrast to the films of Akerman’s male contemporaries, this film addresses the male gaze by avoiding a “voyeuristic” camera, and focuses on the scenes in between the action. Her sophisticated understanding of time and cinematic composition is extremely hypnotic and visceral, and this film really taught me about the unique potential of cinema as an art form.

W&H: How are you adjusting to life during the COVID-19 pandemic? Are you keeping creative, and if so, how?

MD: The pandemic has been challenging, but luckily I have a great filmmaking family at Eyesteelfim, and we are working on a podcast version of “Dope is Death” that will be released at the end of June.