Documentary filmmaker and producer Anaïs Taracena has directed short films “Los Médicos de la Montaña,” “Entre Voces,” and “Desenredar el Ser,” which have been screened at international festivals and universities. “Entre voces” won the public award at the Amnesty International Film Festival in France, the audience award at Pantalla Latina Film Festival in Switzerland, and Best Short at the Bannabá Human Rights Film Festival in Panamá. In 2019, Taracena participated in the Berlinale Talents at the Berlin Film Festival as an emerging director and in the IDFA Academy School at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam.

“The Silence of the Mole” is screening at the 2021 Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Film Festival, which takes place April 29-May 9. The fest is digital this year due to COVID-19. Streaming is geo-blocked to Canada.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

AT: “The Silence of the Mole” is the search for a memory that has been hidden, a reflection on the silences that remain in our bodies in a post-war country through the story of Elías Barahona, a.k.a. “The Mole,” a journalist who infiltrated the heart of one of the most repressive governments in Guatemalan history.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

AT: Some stories make their way to us because they need to be told. First, I met the brother of Elías, the protagonist of the documentary. A year later, an Italian filmmaker and activist who had filmed in Guatemala in the early ’80s passed me a film tape of an interview with Elías in 1983, in which he denounced the human rights violations in Guatemala and the creation of death squads by the state.

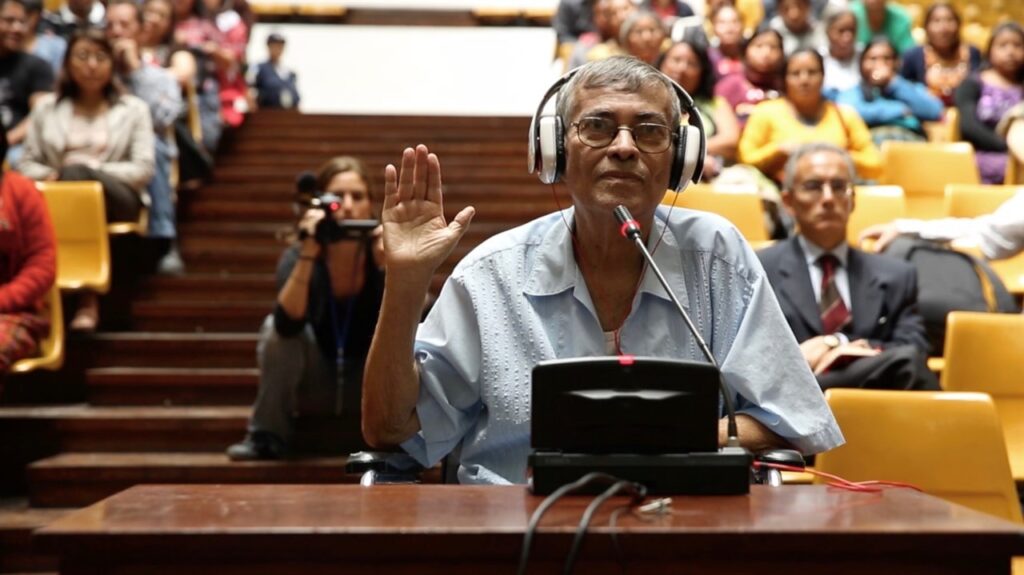

In 2011, I met Elías for the first time and I gave him the film tape of his interview that he had never seen. We became good friends and one day he called me, asking me to film him while he testified at the trial relating to the burning of the Spanish Embassy in 1980, where 37 people died in a fire set by the police, in what is considered the worst urban massacre of Guatemala’s 36-year civil war. Elías died two weeks later.

His death was the impetus behind this film, which has since taken me to the hidden corners of a country scarred by war and the silences that permeate its very streets. What led me to tell this story is a desire to try to understand the generation of my parents and more specifically, the generation of my father, a militant in the revolutionary movement who was exiled for many years.

W&H: What do you want people to think about after they watch the film?

AT: I want people to feel a connection with the film because, beyond being a political film, it is also deeply human and sensitive issue. This story could be told in any other country that has had a civil war.

I want people of my generation – between 30 and 40 years old – who live in Central America to connect with the film. My generation have grown up with many silences and historical gaps, so we had to reconstruct our own memories. Finally, I want to share this with the public because I think that Central American history remains marginal in contemporary historical narratives.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

AT: There were many challenges, I think the first challenge was to face the silences and fears. I spoke with many of the people who do not appear in the documentary, who did not want to be filmed, and who said they preferred not to talk about their militant past.

Then the other challenge is that in Guatemala, archival images have been lost: either burned or rotted. The remaining images of the war are scarce, but many were filmed by foreign journalists. There are few spaces rescuing the visual memory and those spaces work with limited resources.

The archives of the TV news programs can’t be consulted – not a single one – and when you contact an old TV channel, they tell you that they don’t have any archives. So, the pursuit of images of the past was very complex, which is why the search itself is also part of the film.

Finally, to make a film in Central America is not easy – we had to be very patient. There is scant funding so many filmmakers work with no money and the time it takes to make a feature film is much longer than normal. In our case, the crew of “The Silence of the Mole” had to work in different stages.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

AT: The documentary was financed in parts: we obtained international funds over the course of six years. The project won a writing fund in Mexico and another in France, so I decided we were going to shoot the film with that money. Then the project won other funds while we were editing the documentary: we won an international fund in Canada, and a work-in-progress award in Costa Rica and Mexico.

The last funds were very helpful because we were able to finance the post-production of the documentary, which is always the most expensive part. We also obtained funding from the Guatemalan Ministry of Culture, but we were lucky because they only gave it one year.

In total, adding up all the grants over six years, we obtained $30,000 to make the documentary. Of course, the real budget of the documentary is higher.

W&H: What inspired you to become a filmmaker?

AT: I’ve always been curious and inquisitive: since I was a child, I’ve been fascinated by digging in family albums, in the boxes of abandoned archives. My university studies were in political science, but I’ve always been passionate about documentary filmmaking. When I was in college, I saw many documentaries and I even got pirated DVDs to show to my friends and discuss with them.

I told myself that I would love to make documentary films, but I felt I couldn’t do it – until I got into an editing and then a photography workshop. That’s how I started filming and editing.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

AT: I think one of the best pieces of advice is that there are no predetermined ways or formats to tell a story.

I don’t know what the worst advice would be, but I think that saying that only people who study cinema are the ones who can make films is one of the worst things I’ve heard.

W&H: What advice do you have for other women directors?

AT: Definitely encourage them. If women want to tell stories or make films, they should do it. They are not alone. For a long time, what stopped me from making films was that I didn’t dare; I had a lot of insecurities, besides the fact that the industry is still very masculine and sexist. I think the fact that there are more women in the industry makes us feel much more comfortable and accompanied.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

AT: I like many, I don’t have favorites because many inspire me. Many Latin American women inspire me, like Albertina Carri, Lucrecia Martel, Marcela Zamora, Ángeles Cruz, Tatiana Huezo. I also love Agnès Varda.

W&H: How are you adjusting to life during the COVID-19 pandemic? Are you keeping creative, and if so, how?

AT: It has been a very hard year for everyone; we finished “The Silence of the Mole” long distance because the editor lives in Mexico, so everything was slower. In these months, I have managed to film in my neighborhood. With the pandemic, I’ve had much more desire for found footage, and now I’m in the research stage for a short film using only found footage, but I am at the early stage of writing.

W&H: The film industry has a long history of underrepresenting people of color onscreen and behind the scenes and reinforcing – and creating – negative stereotypes. What actions do you think need to be taken to make Hollywood and/or the doc world more inclusive?

AT: It is important to talk about this, as we know the industry is still represented mostly by white, middle class men. But things are changing. It is essential to diversify the voices in cinema: we want more women filmmakers, more Indigenous filmmakers, more young filmmakers. It is important to take into account where stories originate and for whom they are told.

In Central America, there is an emergent diversity of filmmakers — female directors, producers, and photographers — but they are not given the same visibility nor opportunities as the more mainstream filmmakers. In Guatemala, for example, the press has given much more visibility to male than to female filmmakers.

There are also many young filmmakers in many community spaces that promote film and audiovisuals but are not given the same visibility as older counterparts. This is because there is a predominant bias that films not made for international festivals are “second rate.”

For the documentary world, it is important to change the ways of filming, to make them more cooperative and inclusive. There are still many documentaries that are filmed in an extractivist way: some directors film in a certain place but never return, not even to show the film and that is alarming.