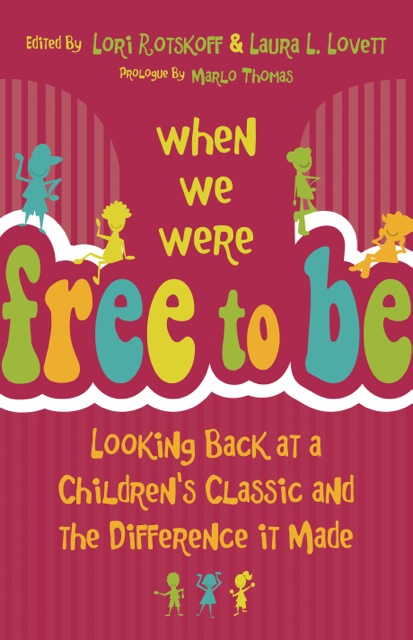

Cultural historian Lori Rotskoff talks with Holly Rosen Fink about her new anthology, co-edited with Laura L. Lovett, When We Were Free to Be: Looking Back at a Children’s Classic and the Difference It Made (University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

Women and Hollywood: Free to Be…You and Me inspired women and children to break down barriers and move the needle on gender equality, but many contributors to your book imply that we have been sidetracked for the last 40 years. How much progress has actually been made?

Lori Rotskoff: We’ve seen a mix of both accomplishments and setbacks. On the one hand, kids are less constrained by gender than they were 40 years ago. Today, a father can change a baby’s diaper and no one raises an eyebrow. Kids know that girls can grow up to be scientists or Supreme Court justices and men can be nurses. Ivy League universities opened their doors to female undergraduates decades ago. On the other hand, children are still limited by stereotypes based on gender, race, ethnicity, and other differences. Toy makers profit by exploiting a “pink and blue” gender divide—with construction toys, robotics, and science kits for boys, and craft kits, fashion dolls, and pretend kitchens for girls. Gender-segregated toys box young people into rigid categories that can limit their aspirations for the future and prevent them from developing a full range of skills and interests. And there’s still rampant homophobia and bullying toward gay, lesbian, and transgender youth.

WaH: While children’s entertainment has come a long way since 1972 when Free to Be…You and Me debuted, when we were growing up, our generation had little entertainment rooted in feminism and devoted to ending gender norms. When will we have a lesbian princess? A fat princess? A bachelorette princess?

LR: There’s been some progress lately. The Disney Channel has a new show called Doc McStuffins that’s popular with parents, educators, critics, and kids. The show reflects the diversity of family life and features an African-American girl whose mother is a doctor and whose father is the primary caregiver at home. As for a lesbian princess or an obese princess? On mainstream TV for kids? Hmmm…I’m not so sure about those. There are so many competing pressures and assumptions about what will be popular and palatable, even when producers want to push the envelope and move things in a more inclusive direction. Given today’s public health campaigns to reduce the incidence of childhood obesity, coupled with First Lady Michelle Obama’s efforts in this regard, I don’t think we’ll see a fat princess dominating the airwaves of children’s programming. The image of an overweight role model seems too controversial.

As for a bachelorette princess, we’ve had one for 40 years now, on the original “Free to Be” album: “Atalanta.” She’s the brainy princess who “ran as fast as the wind” and went off to pursue her own adventures, rather than marry the handsome prince.

WaH: Can you talk about the women behind the “Free to Be” and how they came and worked together?

LR: Marlo Thomas, already famous for her work on the hit television show That Girl, decided to create a new album for children. She was frustrated by the bedtime stories that were available to her young niece, Dionne—stories where the male characters have adventures, solve problems, and save kingdoms from ruin; while female characters gaze into mirrors, tend the hearth, or passively wait to be rescued. Marlo hired the television writer and producer Carole Hart to work with her. They searched for material that wasn’t preachy or saccharine, stories that were clever and edgy, even a bit subversive. At the suggestion of Gloria Steinem, Marlo met Ms. Magazine co-founder Letty Cottin Pogrebin, who became an editorial consultant and helped shape its content. They reached out to writers and musicians and met to discuss the stories and themes they wanted to include. These brainstorming sessions brimmed with energy and ideas—Marlo calls it “collaborative chemistry”—and they resulted in a colorful kaleidoscope of original tales and tunes.

Amazingly, “Free to Be” almost didn’t even get produced, because at first, they couldn’t find a music executive willing to record it. Most of them were put off by the album’s feminism. This is a fascinating story that we discovered when we asked Free to Be’s creators to write their own reflections for our book. When We Were Free to Be offers an “insider’s view” into the creation and legacy of the album, book, and TV special. Stories by artists, activists, journalists, and producers of children’s media reveal not only the artistry and creativity behind it, but also, the public debates and controversies it has inspired.

WaH: Do you think this project could get produced today? How far have women come in the industry since then?

LR: There were certain things specific to the time that allowed Free to Be to have the impact it had: Marlo Thomas’s connections to talented performers; the energy that fueled the women’s movement and other social movements; and the fact that children’s media was becoming more inclusive in terms of race, ethnicity, and gender (think of shows like Sesame Street, Zoom, and the Electric Company.) Social change was “in the air.” But Free to Be was still controversial. The song “William’s Doll,” especially, provoked a conservative backlash because some listeners thought it would encourage effeminate behavior or even homosexuality in boys.

Forty years later, we still have a long way to go when it comes to eliminating gender stereotypes on screen. The Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media offers some sobering statistics. Among the top-grossing G-rated family films, boy characters outnumber girl characters 3:1. And the female characters that do appear are often hyper-sexualized, with tiny waists and other exaggerated body parts. The situation behind the camera is just as bad. Among content creators of family films, only 7% of directors, 13% of writers, and 20% of producers are female. Women’s involvement in the creative process is imperative for reversing the message that girls are less valuable and capable than boys.

Free to Be…You and Me was a big step in the right direction. But gender inequality remains an entrenched problem. Today’s writers, producers, and directors—male and female alike—must do more to create a culture where all children can see a part of themselves represented on screen. The subtitle of our book is “Looking Back at a Children’s Classic and the Difference It Made,” but we also hope to inspire readers to look forward and reimagine a media landscape where every child can truly “run free.”

When We Were Free to Be is on sale now.

____________________________________

Holly Rosen Fink is a writer and marketer living in Westchester, NY.