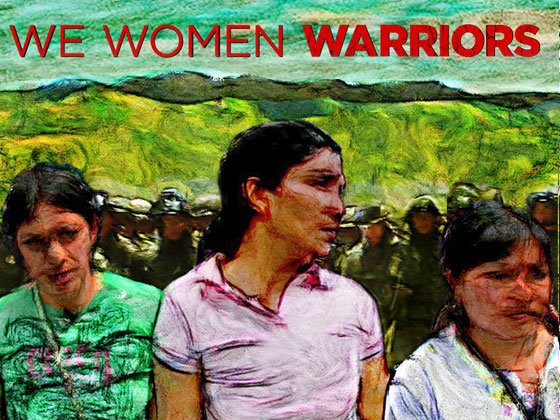

We Women Warriors director Nicole Karsin answered some questions (by email) about her documentary that follows three native Colombian women who are using nonviolent resistance to defend their people during Colombia’s warfare.

Women and Hollywood: You were in Colombia working as a journalist, what made you decide this was a story you had to tell on film?

Nicole Karsin: After covering Colombia’s internal conflict for three years through radio, print and photos, I recognized that Colombia’s humanitarian crisis remained invisible to the U.S. public, so in part, my frustrations and limitations as a journalist prompted me to make this film.

Sublimation was another motive in making this film. Reporting on widespread human rights atrocities and impunity caused me to feel despair and loss. In a three-month period in 2005, I covered the brutal massacre of someone I knew and respected, as well as intense combat that ravaged northern Cauca forcing entire communities to evacuate. I also was affected at the time by assassination attempts against Colombian journalists, who were colleagues and friends. I had seen firsthand how the native communities were caught in the civil war, unwillingly wedged between opposing armies. Their nonviolent stance and conviction to preserve their land and culture was inspiring amid so much aggression.

It was empowering to decide to make a film depicting the plight of Colombian’s indigenous peoples because their courage and unarmed resistance is exemplary. Rural Colombia is also an extremely cinematic setting with stunning landscapes, so it was a pleasure to shoot this gorgeous land, which is what all sides of the conflict vie to control and what the native peoples strive to protect.

WaH: In some way these women are invisible warriors, how can your film raise awareness of their work and what they are fighting for?

Karsin: Hopefully my film will be a vehicle that transmits these women’s voices and provides worldwide audiences access to their neglected crisis and valiant struggles to survive. We intend to have the film’s protagonists present at Q&A sessions as much as possible so they can have a direct dialogue with audiences. The film’s engagement campaign, once it has officially launched, will provide concrete ways for audiences to further be informed about native peoples’ plight and offer concrete actions like petitioning Colombian authorities to respect indigenous rights, supporting native women’s collectives and urging the U.S. government to improve its policy in Colombia with a real regard for human rights that‘s been lacking. We are solidifying partnerships with NGOs that have tirelessly worked on promoting justice in Colombia. Clips from the film will be available as a tool for these groups to help highlight their valuable campaigns.

WaH: How hard was it to get the footage you needed?

Karsin: It was definitely challenging, but I also had some lucky breaks like obtaining the rare permission to bring my camera and shoot in prison the day I met Ludis. I shot for two and a half years pretty consistently while living in Colombia and later did two trips for pick-ups. I was covering three stories simultaneously in three very distinct regions, all war zones. Once I realized how difficult that made things, I was in too deep — committed to the characters and to telling a story with a national scope. Constant diplomacy was required to navigate production and permissions with three tribal governments and their corresponding indigenous organizations.

One time, my backpack containing my clothes was stolen while traveling alone though Cauca to shoot what would be a three-week autonomous process culminating in the Nasa people’s collective action to dismantle police barracks. I’m still very grateful that it was my clothing and not my camera that was taken. Despite taking precautionary measures, another obstacle was being susceptible to illnesses caused by bacteria and amoebas in the villages. There were a few tense moments with the army and police while shooting, but fortunately I didn’t have any run-ins with the guerrillas, which was fortunate considering where I was spending my time.

WaH: Where did you find the women whose stories you told?

Karsin: When I met the film’s protagonists Doris, Ludis and Flor in 2005 and 2006, they were each facing complicated choices, representative of the life-and-death situations in Colombia that remain unbeknownst to many.

I met Ludis Rodriguez, a Kankuamo widow, while she was incarcerated in the Valledupar prison in 2005. I had joined a group of human rights advocates and lawyers from Bogotá investigating the case of some 50 Kankuamos detained on false charges of rebellion and I was granted the propitious permission to use my video camera. There were only five female prisoners, so I interviewed them. Ludis and her fellow inmates related accounts about being captured and framed with trumped up charges. It wasn’t safe to disseminate those interviews at that time, but Ludis’s saga stayed with me and 10 months later I returned to follow her narrative.

On August 9, 2006, the 16th U.N.-declared World’s Indigenous Peoples Day, I met Doris Puchana, an Awá tribal leader, in the office of Colombia’s National Indigenous Organization in Bogotá. Doris had been invited to speak at a press conference at the UN in Bogotá to denounce the warfare in her region causing mass displacements. Early that morning, five people were in her village were massacred by masked men. Doris boldly denounced the massacre on national television, and I met her later that afternoon.

I met Flor Ilva Trochez, a Nasa tribal governor, in September 2006 right after the army killed an 11-year-old boy. She was working alongside other regional leaders to diffuse the crisis caused by the police barracks occupying public spaces that endangered civilians by placing them in the rebels’ line of fire. At that moment, Flor Ilva and other leaders practiced their right to autonomy and self-governance by ruling that their ancestral territories should be free of armed combatants.

WaH: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

Karsin: There were many impediments, but the most severe ones involved my lack of filmmaking experience and securing funding.

WaH: Drugs and the drug war play into these women’s lives their coping mechanism is amazing. What did these women teach you?

Karsin: I am still impressed with their capacity to smile, laugh, dance and make jokes while facing hardships, tragedy and threats. I think this is the most important lesson they imparted — that no matter how desperate the situation, there is hope. Also, the magnitude of their personal resilience astounds me and sets a high bar for which to aspire. Their fierce conviction in defending their way of life and speaking out for justice in a land where impunity reigns is laudable.

WaH: You said you wanted to show women working as leaders peacefully trying to resolve conflicts. What did you learn about women’s leadership from this?

Karsin: In this case, I learned that women’s leadership is connected to motherhood, that all mothers in these communities are leaders. It appears that female leaders are inherently more concerned with improving the world the next generation will inherit and less concerned with leaving their own personal mark on the world. I observed how female leaders are aware of the cyclical nature of Colombia’s conflict and therefore make decisions based on eradicating, not fueling, the generational pattern of revenge and violence. Right after Flor Ilva relinquished her post as tribal governor, her brother-in-law told me that the community wanted her to continue on, but it was her choice to step down. He said they were pleased with their first elected female leader because unlike her male counterparts she did not use her position of power for personal gain and leisure.

WaH: What did you learn most about yourself during this film?

Karsin: I learned that I love storytelling and filmmaking and that I prefer to use these tools to support women’s voices, human rights and dignity. I also learned that I have no tolerance for the grain alcohol manufactured in the native villages.

WaH: What is the biggest takeaway from this film?

Karsin: Speaking out in the face of injustice and harnessing the collective power of unity are critical steps toward resolving Colombia’s conflict and improving our world.

WaH: What advice do you have for other female filmmakers?

Karsin: Follow your instinct, take risks, be pleasantly persistent, be patient in your revision process, actively seek out feedback and support, submit to all grants and funding opportunities. Also attend workshops & discussions like those organized by the International Documentary Association and apply for fellowships like those offered by Film Independent and the National Association for Latino Independent Producers, all of which were tremendous sources of support and helped me craft my film to the best of my ability.

We Women Warriors is screening as part of IFC’s 16th Annual Docuweeks. It will be playing in NYC from August 10–16 and Los Angeles from August 24–30.