For over thirty years, Kim Longinotto has made acclaimed documentaries that have won awards from BAFTA, the Sundance Film Festival and the San Francisco International Film Festival, among others. Her most recent film, “Dreamcatcher,” follows a former prostitute in Chicago who has dedicated her life to helping other sex workers. In recognition of her body of work, Longinotto will be awarded the Robert and Anne Drew Award for a mid-career filmmaker concentrating on observational cinema at this year’s DOC NYC Film Festival. (DOC NYC).

Longinotto spoke to Women and Hollywood about her prolific output, her troubles securing funding despite her long and acclaimed career and the important role her lack of confidence has in her filmmaking process.

This interview has been edited. It was transcribed by Laura Nicholson.

W&H: What does it mean to you to be receiving DOC NYC’s award for documentary excellence?

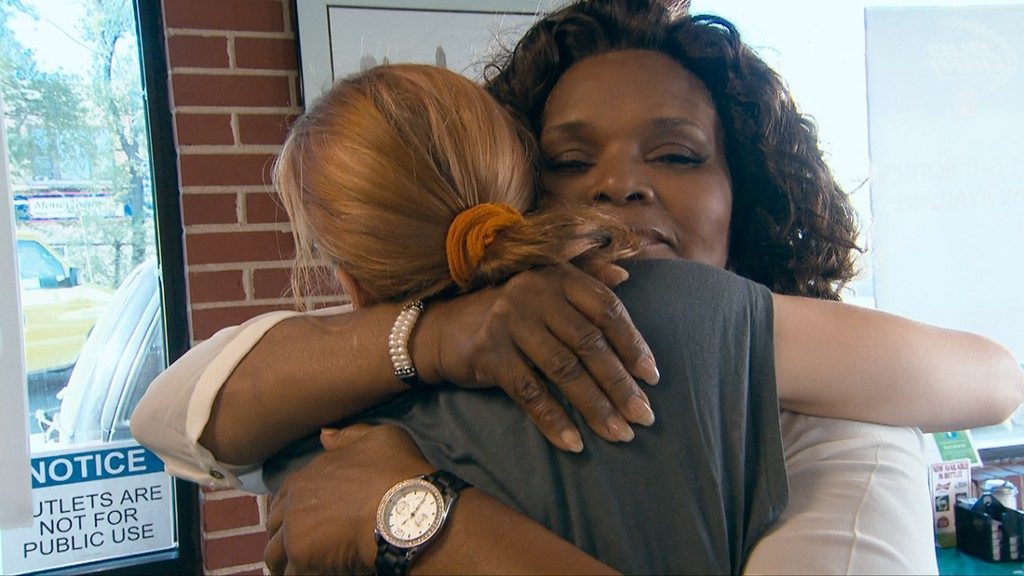

KL: I love it, because it’s such a big thing for people to do these films with me. I’ll talk about “Dreamcatcher” because that was the latest one: It was an extraordinary leap of faith for those girls at the school and on the street to say that, through 10 weeks we’re going to share these incredibly intimate moments with you. What this award meant for me is that the film has spoken to people — that people have seen the film and these women have meant something to them. That’s the most important thing. It makes me so happy. We all have these very dark days when you think, “What am I doing? It’s so hard to get films made” — and then there are brief moments when you think, “God, they’re made — and people actually like them and it’s meant something to them.” The award is for all of us — it’s for the team.

W&H The award is also for your body of work. You’ve told stories about those you call “rebels,” who mostly turn out to be women.

KL: Yes. The body of work is like an army of women, from Samprat Pal [an Indian women’s rights activist, appearing in Longinotto’s 2010 documentary “Pink Saris”] to the women who demanded their right to a divorce through the Iranian court system in “Divorce Iranian Style” to women fighting against FGM. It’s all the young girls and women who have stood up to say, “No, we’re not going to put up with this.”

W&H: Why do you think you’re drawn to these types of stories?

KL: It’s knowing that these are good stories — stories that have a beginning, a middle and an end, and audiences will be gripped — there’s a point to it. There was a story that I was frightened to make, and it was “Salma” (2013). It had happened in the past, but I had to make that film. You never hear from the women who have managed to rebel against their imprisonment. There were thousands of us across the world campaigning for Nelson Mandela’s release, but these women just disappear — so when one of them escapes with her own poetry and then becomes a politician, it was too good an opportunity to miss. But it was a terrifying film to make because I knew that Salma and I would have to create the film in a very different way. The stories I’m drawn to in the films that I’ve watched, like “Arne Dahl,” “Boyhood” and “The Lives of Others” are all about change. I love watching people changing and growing — becoming something different. When you’re a rebel, you’re testing yourself and you’re testing the limits of everything around you. The reason I’m attracted to stories of rebels is because they’re changing things.

W&H: Do you ever enter into a documentary project never knowing what the ending is going to be?

KL: I always know what the film’s about, and I’m very disciplined about what I film. But the actual ending, I only really know after I’ve filmed it. For example, in “Hold Me Tight, Let Me Go” (2007), this kid plays Labi Siffre’s “Something Inside So Strong,” and after he’d played it on this little machine that he’d just been given, I said to him, “Robert, that’s the end of the film,” and he looked at me as if I were mad, because to him he was just playing a song.

W&H: You also act as cinematographer in all of your films. Can you talk about how you made that decision?

KL: There’s a pragmatic reason. If you think of how “Dreamcatcher” was made with Brenda Myers-Powell, it’s me and the sound recordist, and I couldn’t be in the car with her if I had a separate cinematographer. As it was, Brenda and one of the girls would be in the back, while the sound recordist and I would be in the front — that was the only way you could film it. I don’t know where a third crew member would sit — probably on the bonnet [the hood of the car]! It’s a question of space, but also, I think we make the kind of films that reflect the kind of person we are, and I would find it very difficult to tell somebody what to do — I wouldn’t want to do that. Also, I know exactly what sort of shot I want, and I know that I will film it so that it’s very easy to cut. I put it together as I’m shooting it. I thought, “I want to learn how to do this properly, so I’m going to do it — there’s nobody else to blame if it goes wrong.”

W&H: You talk about being really disciplined and you don’t shoot a lot of footage. Is that by necessity in terms of finances, or is it a filmmaking choice?

KL: I don’t want the people I’m with on this journey to feel like I’m filming them all the time. I don’t want them to constantly feel as though they’re being watched. So I will have the camera ready at all times, but I will only film when something is really worth filming. Those are the moments when the person being filmed is usually not aware of it. In “Dreamcatcher,” when Brenda was in the back of the car and Marie was saying, “I want to go to rehab, you’ve got to save me,” the last thing Brenda is thinking of is this very sweaty woman in the front of the car desperately trying to capture it. Even though I’m only a foot away, nobody was aware of me filming it. So there’s not this sense of being filmed all the time — I’m just with them, hanging out, but then the moments where they want to talk to me, they can. It’s all about learning through watching.

W&H: Do you have a favorite of your films?

KL: No. I think what always happens is that, with the last one I think, “Oh God, I love Brenda!” — because I do passionately love her — and “that’s my favorite film.” And then I’m in the middle of setting up a new one, and I’ll probably fall in love with that one. There’s no point in making something if you’re not falling in love with the people you’re filming and you want them to really enjoy you being around. It would be weird if, when you’re making a film, you don’t think it’s going to be the best ever or the worst ever — I guess it goes from one feeling to another. I usually have a month of thinking it’s not going to work.

W&H: Are you thinking about another “rebel” woman in your next film?

KL: Yes. It’s a little rebel group of people; there are three of them.

W&H: Do you ever go back to revisit some of your subjects to see where they are now?

KL: I’m in touch with all of them, and usually try to help them all in some way or another. There’s this wonderful woman I met in Nairobi when she was about eight, and she’s now in university in New York. I’m so proud of her — that she’s come from that location and is now studying to be a doctor. I followed her all along the way, and that’s a really great feeling.

W&H: Could you talk a little bit about the funding for the film?

KL: It doesn’t get easier. It’s the same for the commissioning editors — they’re worried that they will give money to somebody and not get a film out of it. They want you to tell them what the beginning, middle and end of a film is, and of course, if you’re making a film honestly, you can’t predict that. You have to go on these journeys and trust that it will happen and it’s always hard — I usually try to find a commissioning editor and stick with them. My commissioning editor left and was replaced with somebody who didn’t want to make the kinds of films that I do, because they are risky. I can’t say that a certain film will definitely work; I can’t give any assurances. I’ve been lucky up until now, but there’s always next time when it might not work. I’m not going to lie to them. When I was fundraising my last film, they asked whether it was going to be good and I said I didn’t know, and the producers were rightfully cross with me because they said I’d talked myself out of the money.

W&H: Do you think they ask male filmmakers if their movie is going to be good?

KL: I don’t know — that’s interesting. I would say it’s more the case that people like me who don’t have a lot of confidence, don’t usually say that they think they’re going to make something good. I told my last commissioning editor, when I was making “Salma,” that I thought it was going to be a risk and that I’d do my best, but it was going to be hard. He ended up saying, “Kim, you can do it” — and that’s what was extraordinary about him, I made three films with him, and that’s how it happened. The new people weren’t going to say, “Kim, you can do it” — they wanted me to say, “I can do it. Trust me. Give me the money.” That’s how they wanted it to work.

I would break it down as: Confident people — who tend to be men (although in 2015 I’m not generalizing anymore about men and women, because I think these old terms of “masculine” and “feminine” are going very fast with the rise of transgender rights that are questioning what all these categories are). We’re realizing that just to get a powerful woman isn’t necessarily going to be better than a powerful man. It’s what they stand for — are they corrupt? We’ve seen it so many times in India. There was Mayawati, who stood on a platform as an “untouchable,” woman and then let everybody down. We have wonderful, confident women like Kathryn Bigelow who made a film that won an Oscar and I’m proud of her, but you wouldn’t necessarily watch that film and say it was a woman’s film. I don’t think we can generalize — I don’t think we ever have been able to. The only place you can generalize is somewhere like Iran, or Pakistan, where the Taliban are there shooting girls in the head for going to school — and those men have been brainwashed to think that men and women are completely different.

W&H: But when men go in and ask for money, it is assumed that they have the confidence to make that next movie — especially if they have a track record — versus when women go in, there are different expectations related to confidence. You are a director with a big track record. Does that help you in conversations related to funding?

KL: No, I’ve learned that it doesn’t help. Last year, I came to America to get the funding for this film. In the end, I didn’t raise the money. The producer did. I wasn’t in the room, which was great because he was able to say whatever he said and raised the money without me there. I think he realized I was a bit of a liability. I’m too honest.

W&H: Do you think you should have told them it was going to be a good movie and then taken the money and just figured it out later?

KL: I don’t know that it’s going to be a good movie. I just do the best I can, but they are journeys and they are risks. That’s why I say that the award isn’t just for me — it might sound disingenuous, but it’s not. I couldn’t say that Brenda was prepared to let me into her life. I wouldn’t want to go and meet her without the camera and try it out. As soon as you haven’t filmed something, you’ve lost that moment forever. I want that to happen truthfully. I think the only reason she was able to do it is because I’m not a confident person. Those confident men and women you talk about, they probably make very different films than I do. I make films about other people that are also outsiders and misfits and usually quite damaged — we recognize each other, we love each other and we make films together. I think that if I did go in with “swag” on, I don’t think it would work. This is who I am, and this is how we seek each other out — that’s why people ask me to make films about them. I wonder if these confident men really exist. Where are these human beings that are totally confident? I don’t know if they exist.

W&H: How do you go about documenting these difficult stories?

KL: I think that to write about these things really well and honestly, is a very challenging task. We need to really think imaginatively and differently. It’s not just getting women into these jobs, it’s what these films are about — films that are making us redefine our own lives. For example, what Brenda’s saying is, “I was on the street for 25 years — I’ve now survived — but I’m also still really hurting inside.” There is hope for us all. I was thrilled that Brenda had the courage to talk to Homer (the pimp in “Dreamcatcher”) about victims potentially becoming victimizers.

It’s never as simple as the victim always being the victim. You see it everywhere: Mugabe became a dictator after being a freedom fighter — sometimes people want revenge. Brenda, who started off as a frightened, little 11 year old sitting in cars with men, is then finding vulnerable, little 11 year olds on the street and handing them over to her pimp before having a breakdown about it the next day because she feels so bad. That, to me, is the most important scene in the film, and a lot of people wanted us to take it out, because it made them feel uncomfortable. People want black and white answers, but it’s not one thing or another. I think the only way we’re going to make good things in 2015 is to inspire people and make them feel as though what they’re watching is real.

Please check out The SundanceNow Doc Club has a current retrospective of Longinotto’s career.