To be out or not be out, that is the question.

Whether ’tis nobler to come out definitively and suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous publicity or to take arms against the sea of labels and by opposing them enter a new age of nonchalant sexual otherness.

Good question.

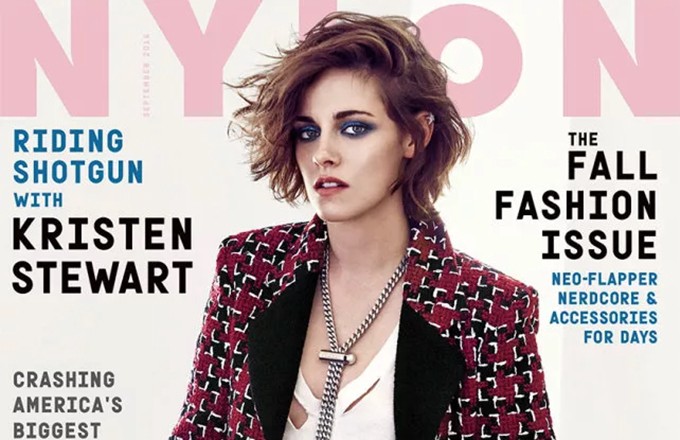

This week child star-turned-reluctant teen idol-turned-sullen international box office-magnet Kristen Stewart made headlines by not coming out, but also not hiding her sexual orientation. In a cover story for Nylon magazine the 25-year-old actress was as candid as someone can be about her personal life without actually spelling it out.

“Google me, I’m not hiding,” she told Nylon. “If you feel like you really want to define yourself, and you have the ability to articulate those parameters and that in itself defines you, then do it. But I am an actress, man. I live in the fucking ambiguity of this life and I love it. I don’t feel like it would be true for me to be like, ‘I’m coming out!’ No, I do a job. Until I decide that I’m starting a foundation or that I have some perspective or opinion that other people should be receiving… I don’t. I’m just a kid making movies.”

The media has long puzzled how, exactly, to cover the sexual orientation of public figures who have not yet made declarative “Yep, I’m gay” statements. The hard and fast rule has been to never “out” LGBT celebrities, though politicians and other officials who espouse harmful and hypocritical public policies remain the notable exception to said rule.

Recently, that mindset has resulted in many stubborn headlines about Stewart spending time/holding hands/cuddling on the beach with her “gal pal” Alicia Cargile. Like, isn’t that sweet? Aren’t female friendships precious? The limbo some have undertaken to not state the obvious has been almost silly at times.

Of course, Stewart is not the first famous woman to cause confusion by eschewing direct definitions.

Jodie Foster famously came out in a deeply personal and fascinatingly rambling speech at the Golden Globes in January 2013. Yet for many news organizations, the “coming out” part remained in quotes because the Oscar-winning actress never once uttered the words “gay” or “lesbian.”

Before that, Lindsay Lohan confounded the tabloids in 2008 by her obvious and open relationship with DJ Samantha Ronson. At the time, Lohan had not come out in any official sense about her sexuality or relationship. But then she was asked directly by Harper’s Bazaar in a November 2008 cover story.

“I think it’s pretty obvious who I’m seeing,” she told Harper’s, and then went on to say she maybe identified as bisexual, but definitely not as lesbian. “I don’t want to classify myself. First of all, you never know what’s going to happen — tomorrow, in a month, a year from now, five years from now. I appreciate people, and it doesn’t matter who they are, and I feel blessed to be able to feel comfortable enough with myself that I can say that.”

The desire to remain label-free and/or open to anything is certainly not a new one. But it is one being expressed more and more of late in particular by younger female celebrities. Miley Cyrus is among those happily leading the charge for sexual fluidity. In June she told Paper magazine that she has had and is open to all forms of relationships.

“I am literally open to every single thing that is consenting and doesn’t involve an animal and everyone is of age,” she told Paper. “Everything that’s legal, I’m down with. Yo, I’m down with any adult — anyone over the age of 18 who is down to love me. I don’t relate to being boy or girl, and I don’t have to have my partner relate to boy or girl.”

Joining Cyrus in the ranks of down for anything is the actress Maria Bello, who in November 2013 came out as “whatever” in a New York Times Modern Love column, and model-turned-actress Cara Delevingne, who defended her sexuality in a New York Times feature by saying, “My sexuality is not a phase. I am who I am.”

Yet the act of coming out in the LGBT community is an undeniably powerful one. Throughout history, the movement has made significant societal strides by the simple act of stating the love that once dared not speak its name.

The world changed in 1997 when Ellen DeGeneres leaned over and declared, quite literally into a microphone, “I’m gay.” And in February 2014, Ellen Page handed queer people young and old a Valentine’s gift to remember when she told the crowd at a Human Rights Campaign conference, “I’m here today because I am gay.”

Those moments, those unabashed admissions of self, had real and lasting importance. Our current civic gains prove the longstanding theory that the more people see and get to know us, the less likely they are to fear and hate us. Coming out remains vital in so many ways, both personal and political. So with it comes a tacit judgment on all those who choose to remain in the closet, particularly for public figures. If it takes bravery to come out, the thinking goes, the opposite is involved in staying silent.

Yet it remains critical that we never stop acknowledging that the coming-out process continues to be a truly intimate, sometimes radical and too often dangerous endeavor that should only be done on each person’s own terms. And just because people are in the public eye does not mean we are owed any special insight into their private lives.

But now, with this new breed of non-coming-out coming out statements, the fundamental question has shifted. There is now a camp that, while not hiding, is steadfastly not labeling itself. Like Stewart, they are not necessarily closeted, not necessarily out. And there is something undeniably powerful in that, too. Some might even say they are the harbingers of the utopian post-gay world longed for in gender-studies lore.

Stewart basically said as much to Nylon as well: “I think in three or four years, there are going to be a whole lot more people who don’t think it’s necessary to figure out if you’re gay or straight. It’s like, just do your thing.”

That would seem a rather optimistic projection, given the very real discrimination and violence still faced nationally and internationally by LGBT people. But the freedom to just be ourselves remains at the core of our community. Whether that means declaring, “I’m here, I’m queer, get used to it,” or a more unspoken yet adventurous approach to the Kinsey scale, it would seem we are all after the same goal.

So perhaps, with all due respect to Shakespeare, the question has been framed wrong. Quite simply, being out is no longer just an either-or question. For those who feel confident and comfortable enough call themselves lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer or whathaveyou, that’s a great thing. And for those who truly feel they don’t fit into any one category, yet want to be accepted for who they are, that’s a great thing, too. All who are open and honest with themselves should be welcome under the big and ever-expanding umbrella of sexual otherness.

Perchance it’s not too much to dream for, after all.