Hanna Polak is an Oscar-nominated director. She has worked on various movies as producer, director, cinematographer and still photographer. In 2002, she was awarded Best Producer of Documentary and Short Fiction Movies in Poland for “Railway Station Ballad.” In 2004, she completed work on “The Children of Leningradsky” in collaboration with HBO. The movie received an Oscar nomination (2005), an IDA Award, two Emmy nominations and the Gracie Allen Award, among others. Polak has been advocating the case of homeless children all over the world. She founded and collaborated with the Active Child Aid foundation and collaborates with UNICEF. (Press materials)

The documentary “Something Better to Come” will premiere at the 2015 BFI London Film Festival on October 12 and opens in LA October 24.

W&H: Please give us your description of the film playing.

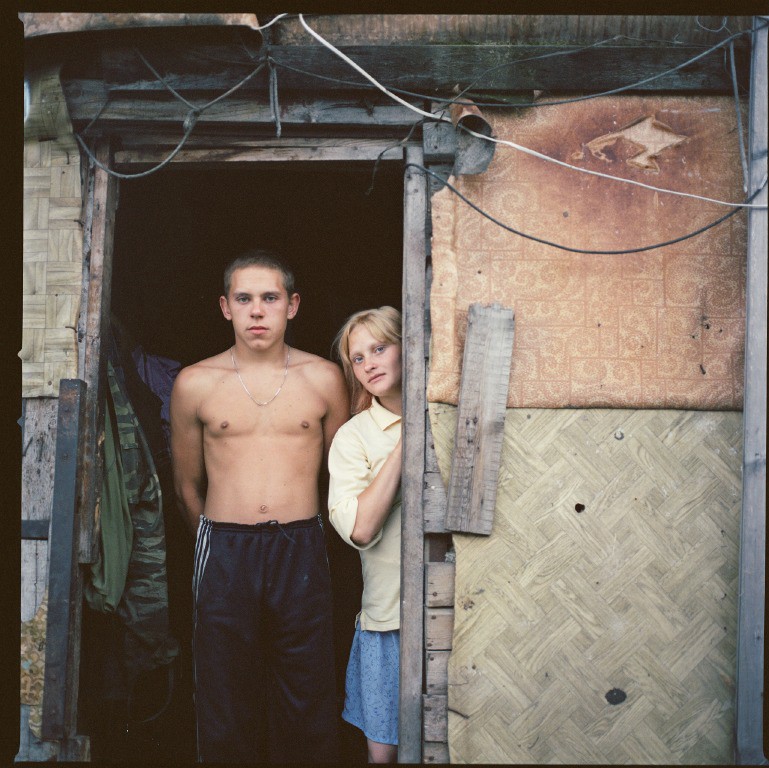

HP: Ten-year-old Yula grows up only 13 miles from Red Square and the Kremlin. Her “home” is the largest garbage dump in Europe, in the suburbs of the largest city in Europe, Moscow, where the mafia runs a multi-million-dollar business of illegal recycling, and where people like Yula have no rights and simply don’t exist in the external world. Looking at Moscow from afar, Yula dreams of a normal life other people are able to have. For 14 years, we accompany Yula as she comes of age and matures, to the point when she takes her destiny in her own hands. It is an inspiring story of hope and Yula’s ultimate strength.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

HP: It started with me meeting homeless children on the streets of Moscow. Being aware of the fact that others were indifferent towards their life and death — I felt they mattered to me. Despite all the direct help I could offer to them, I thought I had to make a film to show their unbelievable situation — and also their beauty, to make people aware and do something to save their lives, to change this shameful and crazy situation. Personally, I could not turn a blind eye to this. I could not simply forget and go about my own life, passing these children on the streets, acting oblivious to their suffering and not do something to save at least one of them.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

HP: This whole project was a challenge from beginning to end. Everything was a challenge. It was forbidden to shoot at the dump. I had to sneak in and out, hide, run away. I was caught by security and police many times, and my filmed materials were destroyed. It was incredibly dangerous; I would carry a knife, a taser and pepper spray with me. It is a criminal environment where human life has no meaning, and I knew that once inside, the same lawless situation [would] apply to me. I could be murdered or raped at any time and buried under tons of garbage.

And making the film itself, well, there was no money, as no one would fund a film for 14 years! The editing of a time-lapse story is the biggest challenge. How do you condense 14 years of somebody’s life to 90 minutes? But today, the film is appreciated by audiences and winning awards and I can forget all the hardships that I had making it. How can I possibly compare my hardships to those of Yula’s?

W&H: What do you want people to think about when they are leaving the theater?

HP: I want people to be inspired by the fact that if Yula could achieve the impossible in her life, we can also. I want people to see how important that moment is — the decision to do something about their life, and then doing it. I think this is the powerful message and experience that comes from this film. It’s a great inspiration. I also want people to do good for others for those near and far. After seeing my film, one woman told me: “I promise you I’ll be a better mother,” so that also makes me extremely happy.

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

HP: Be creative and make projects you believe in and are inspired by. In the end, I will learn from them how to make outstanding films.

W&H: What’s the biggest misconception about you and your work?

HP: I am often asked why I didn’t help Yula, but in fact I did help her and other homeless children in many ways, [including] cooking for them, collecting and distributing clothes, [offering] first aid, placing children in hospitals and orphanages, renting an apartment near where many were homeless so they could come and receive immediate help there and allowing many to stay in this apartment [so they could] get out of the street and out of the dump.

But this is not what the film is about. I didn’t want to make a film about myself, about what I did for these children and for Yula. The aim was to show the real lives of Yula and other kids to influence regulations and policies that need to be changed.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

HP: It was extremely difficult to get financing for the film. I wrote many submissions for funding with little success. One day, I met Sigrid Dyekjaer from Danish Documentary and the situation changed. With a strong producer and funding from the Danish Film Institute and the Polish Film Institute, we were able to create a great team, and only then were we able to finalize the project. We also received support from HBO Europe and other TV broadcasters. Jan Rofekamp, the official distributor of our movie, played a big part in that.

We are still seeking funding to promote the film. I have to say that it is sometimes very frustrating how much time you have to spend on finding financing for the film instead of making the film.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

HP: “Fish Tank” by Andrea Arnold. It’s fantastically edited by Nicolas Chaudeurge and the acting is great. Another would be the Sundance winner Anna Melikyan’s “Mermaid.” It is just such a sweet film with lots of humor and creativity.