Photographer-turned-film festival founder- turned-director Nancy Buirski’s first film was the documentary The Loving Story, a look at the 1967 Supreme Court case that made interracial marriage legal across the United States. In her latest work, Afternoon of a Faun, Buirski returns to her aesthetic roots by exploring the life and career of the French-American ballet dancer Tanaquil Le Clercq (1929–2000), whose legendary career was cut short at 27 by polio.

Afternoon of a Faun will be released (in NYC) on Wednesday, February 5th and will also play in the Berlinale.

What drew you to this story?

Tanaquil Le Clercq is mythic. She is also one of the most mesmerizing figures I have ever seen on screen. Not only was I seduced by her beauty, her elegance, and her genius as a dancer, but the fact that this unique talent was felled by polio was too much to bear. It’s chilling.

Why the story of “Tanny”? What does she teach us?

That disease or limitations coming with age spare no one, no matter how privileged or talented. It is the acceptance of that fact that ultimately tells us who we are. Tanny did not overcome her disease. She did not triumph over polio. She coped, and she reconciled with her fate. And she lived a life very much in the moment, as all dancers do. Life is fleeting for all of us. We should take heed.

Talk a little about the title.

Jerome Robbins created his radical ballet Afternoon of a Faun for Tanny. He chose to have his two dancers rehearsing in a studio, observing themselves in a mirror, as dancers do when they practice. And he brilliantly chose to have the audience serve as that mirror. So not unlike Nijinsky’s original Afternoon of a Faun, where he danced Narcissus looking at his reflection in a lake, these two dancers are dancing their narcissism, observing the movement of their bodies. The look of their dance and the look of their bodies is as important as the feel of them. So he has integrated the audience with that narcissism — quite an amazing concept when one thinks of performance in general.

And dance is about movement. It is profoundly physical, and that is what Tanny lost. It is what all dancers eventually lose as they age out of their abilities to transcend gravity. Her story is pure poetry, the poetry of dance. Our story portrays the afternoon of a dancer, of all dancers.

The film is quite emotional. How did you achieve the emotionality?

Storytelling for me is as much about the emotional reality of the subject as the literal one. To feel what Tanny was feeling, I needed to tell her story from the inside looking out, not the other way around. There is no voice of God commenting on her life; neither are there dance or polio experts brought on stage to educate us. Our witnesses are friends of Tanny’s who lived her story with her, were intimately involved with her. We either hear from Tanny through her letters, and, in a few cases, her own voice, and from her friends. They seem to tell her story as if it were yesterday. That’s how vivid she was — and still is — to them.

What were the biggest challenges in putting this film together?

There are always two challenges when making a film about a deceased subject. Finding the means to tell the story visually — through footage and stills — and creating an intimacy with the subject, who is not alive to tell her story. No matter what materials I used, I wanted viewers to feel close to Tanny — ideally, to feel what she was feeling. As in The Loving Story, I wanted us to get under the skin of a transformative subject, not experience her from afar. It is her story to tell.

Martin Scorsese is the project adviser. How did he advise?

We discussed the essence of the story from the beginning of my work on it. Coming to grips with that is a long process, and he helped me wrestle with it. He also gave my editor Damian Rodriguez and me great notes, which, needless to say, we took!

How did your experience as a photographer help in making this film?

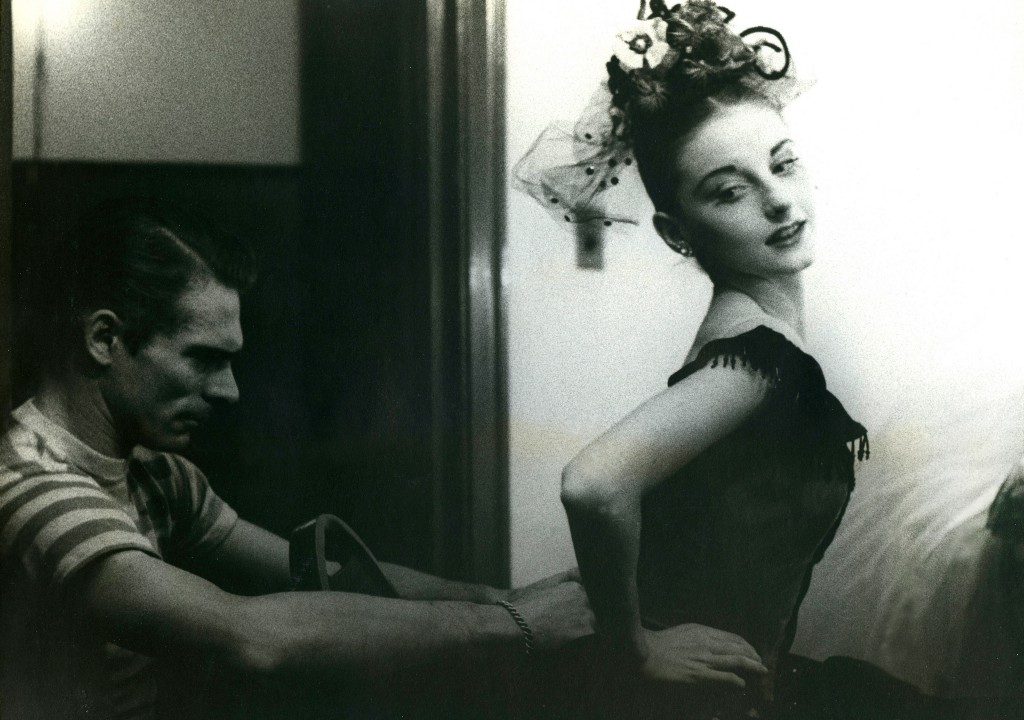

My work in photography not only refined my visual sensibility, but affected the way I’ve used photos in film. The sequencing and pacing of images have become essential narrative tools for me. We had an abundance of very fine photographs, from well-known and lesser known photographers, that became a strong narrative and emotional thread in Afternoon of a Faun, much as it was in The Loving Story. Vintage footage and stills help one create a unique aesthetic. They are magical, a gift.

Your film played at the NY Film Festival and now is going to Berlinale. How excited are you by the worldwide reception?

Over the moon!

Can you share any advice for other women directors?

Never take no for an answer. And make your film’s subject personal, even if it doesn’t start out that way. I guess this is advice for any filmmaker, though the word “no” comes up more often for women.

What’s next for you?

I’m moving into narratives. I’ll next direct Endangered, a hybrid animation and live-action film based on the award-winning YA novel by Eliot Schrefer of the same name. I’m excited and terrified. I’m also a producer of the narrative version of The Loving Story (with Colin Firth and Ged Doherty), as well as a two-part miniseries, The Donner Party, in development at HBO Original Programming with Ric Burns. I’ve got a few other doc ideas — all in all, an embarrassment of riches. Having started this chapter a bit late, I’m trying to make up for lost time.