Ivy Meeropol’s documentary feature debut was “Heir to an Execution,” which premiered at the 2004 Sundance Film Festival, and was shortlisted for an Academy Award. It was followed by two short films in 2016 for the Emmy Award-winning documentary series “Years of Living Dangerously,” and the feature-length documentary “Indian Point,” which premiered at the 2015 Tribeca Film Festival and received the 2016 Frontline Award for Journalism in a Documentary Film. Meeropol’s television credits also include an episode for CNN’s docu-series “Death Row Stories,” and “The Hill,” a six-part series she created, directed and produced.

“Bully. Coward. Victim. The Story of Roy Cohn” will premiere at the 2019 New York Film Festival on September 29.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words

IM: The film is an exploration of the complex character of [American lawyer] Roy Cohn, looking beyond all the many contradictions that informed his life, in search of the human being lurking behind the Machiavellian persona.

I began by considering my own family’s interaction with Cohn when he was a young assistant prosecutor in my grandparents’ — Ethel and Julius Rosenberg’s — trial. Cohn doggedly pushed for my grandparents’ execution, so this was a natural part of my exploration, but my family’s experience is only one point of view.

Cohn was a deeply complicated person, which is why I sought out people who knew him intimately and could speak about him beyond the courtroom. This is a man who seemed to draw on his own self-loathing as a closeted gay Jew to fuel the vicious, frequently criminal tactics that gave him such notoriety. And, while our topic is often grim and sometimes upsetting or even infuriating, the film aspires to capture Cohn’s point of view – how he saw life, in general, and his own life, in particular. In this sense, the film is at times a study of a lost character inventing his way forward in life.

We cover the parts of Cohn’s life where he may have had some semblance of happiness and fulfillment. Moving between these different states of being reflects the way in which Cohn moved between worlds during his life, and how he protected himself – no matter the cost – which all too often came at the expense of many people rather than himself.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

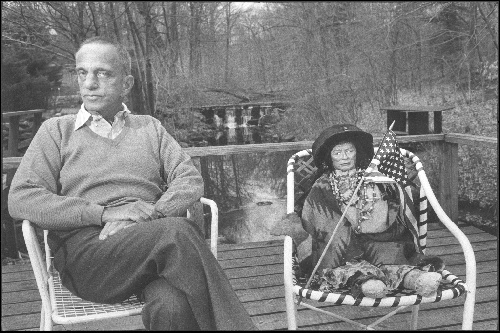

IM: I thought about making this film for many years, and my family connection to Cohn gave me a natural entry point into his life, but it really was an experience I had in 1988 when my father and I were in DC: we discovered Cohn’s name on a panel on the AIDS Memorial Quilt. We were both stunned by this.

That stayed with me for decades, thinking about the role this man played in my family’s lives and how much we actually didn’t know about him. The idea of who Cohn was publicly versus privately made me return again and again to the idea of a film. Finally, when Trump was elected — Cohn was his attorney and close friend — and then “Angels in America” [in which a character is based on and named after Cohn] returned to Broadway, I felt the time was exactly right to find my way into his story, and make this film.

W&H: What do you want people to think about when they are leaving the theater?

IM: The specter of Cohn looms over my family, but I wanted to know the human being behind those malevolent eyes. I want audiences to also get beyond the pat descriptions of Cohn as “evil.” We give him and others like him too much power when we don’t look deeper as to how they are able to wield their influence.

Calling someone evil oversimplifies their acts, and in a way exonerates them from all the crimes they perpetrated in life. He chose his own course. I wanted to understand the circumstances that produced his outlook on the world but also find a way for audiences to make their own conclusions without telling them exactly how to feel.

That said, I want people to feel that societal bigotry destroys lives and that Cohn’s way of dealing with his fear of his own sexuality along with his self-loathing was to destroy others. His actions and tactics throughout his life are unforgivable and reprehensible yet we get nowhere without looking behind those tactics.

I want people to understand why Donald Trump’s relationship with Cohn is critically important, and help audiences to gain a deeper insight into how Cohn helped set Trump on a path that reverberates today.

This film is my way of impressing upon audiences that the past is very much present, and we would be wise not to forget how we got here.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

IM: It was very challenging figuring out how to use my family story in the film, both coming up with how to integrate my father, but also weaving in that family story in the edit until we were able to make sure the balance worked well with the many other storylines.

Because of my family’s experience with Cohn, I despised him since I learned his name yet to make a film about him I had to overcome those preconceived notions. I was not going to make a one-note film about an evil man, so finding a way to humanize Cohn without forgiving him was also a challenge.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

IM: We self-funded our initial development and research, and then we entered into discussions with a couple of potential funders. I had made my first feature with HBO, and when we had early conversations with them, it was apparent that they were very interested. They gave us development funding, and we used that to create further materials, including key excerpts from the first audio tape we secured from journalist Peter Manso.

We met with Nancy Abraham and the team at HBO, and reviewed the materials together. They greenlit the production, and we were off and running with wonderful and supportive partners.

W&H: What inspired you to become a filmmaker?

IM: I love hearing other people’s stories and especially how they tell them. I was working in politics, and then as a journalist and aspiring screenwriter when I made my first documentary, “Heir to An Execution.” I had wanted to contribute something to the many versions of my grandparents’ story, and felt at the time that it had to be a documentary because I wanted to hear directly from people who knew my grandparents, and could share their stories more directly with audiences in a way that writing didn’t allow. It was a case of the story dictating the medium and I fell in love with the medium.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

IM: Best advice: After a presentation to a group of funders — which I knew hadn’t gone well — a woman came up to me and said, “You have a great project here, and a lot going for you, but you have to own it!” I knew immediately what she meant, and we reworked the pitch to incorporate more of me, and why I was the person to make that particular film. I needed to show how much I believed in the story and in myself. The next day we pitched again and knocked it out of the park.

The worst advice came from a male producer: “You don’t have a film if you don’t confront or ambush [subjects] directly.”

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

IM: Understand and use your strengths — they may not be the same as a male director. Don’t feel the need to emulate the model that’s been created by the male stars of the profession.

Also, as you set the working environment of the production, never lose sight of how essential true and respectful collaboration is in filmmaking. Directing means having a vision but also being a leader who can work with everyone on the team.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

IM: One of my favorite woman-directed films is “Salaam Bombay!” directed by Mira Nair. It was her debut feature, and I think it’s so immersive, how it’s set in the real city where it takes place like a documentary, yet is so beautifully filmed and dramatized that it becomes that rare film that creates a world that feels real and so close that you experience the characters and their emotions very directly and deeply.

W&H: What differences have you noticed in the industry since the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements launched?

IM: The documentary industry has always had a large percentage of executive and decision makers who are women – for many reasons, including that documentaries haven’t had big budgets or been regarded as competitive in the film landscape, until recently. The leadership of women in the documentary world has given us an advantage long before #MeToo and #TimesUp.

That said, executives still tend to favor male directors and producers for big ticket stories and bigger budget films, and that seems to be shifting post #MeToo and #TimesUp. Hiring women across the board is more of a priority even in the doc world. Executives are more motivated to bring on women directors as well as highlighting the work of female cinematographers and other key crew who are women.