Lynn Novick is an Emmy, Peabody, and Alfred I. duPont Columbia Award-winning filmmaker. For 30 years she has been directing and producing landmark documentary films about American culture, history, politics, sports, art, and music. With co-director Ken Burns, she has created more than 80 hours of acclaimed programming for PBS, including “The Vietnam War,” “Baseball,” “Jazz,” “Frank Lloyd Wright,” “The War,” and “Prohibition.” “College Behind Bars” is her solo directorial debut.

“College Behind Bars” will premiere at the 2019 New York Film Festival on September 28.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

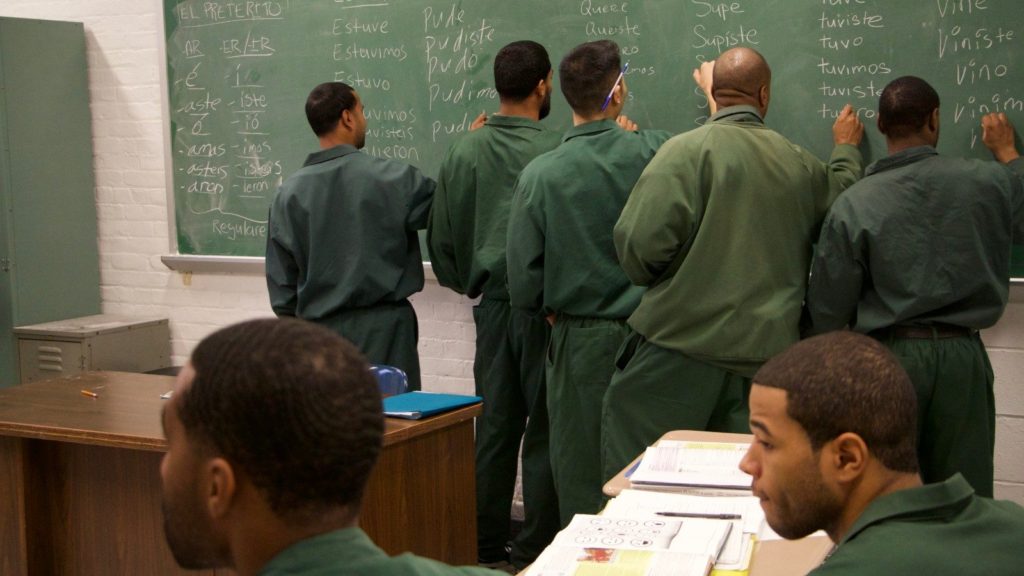

LN: “College Behind Bars” is a four-part documentary film series. It tells the story of a small group of incarcerated men and women struggling to earn college degrees and turn their lives around in one of the most rigorous and effective prison education programs in the United States: the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI).

Shot over four years in maximum and medium security prisons in New York State, our four-hour film takes viewers on a stark and intimate journey into one of the most pressing issues of our time – our failure to provide meaningful rehabilitation for the over two million Americans living behind bars.

Through the personal stories of the students and their families, the film reveals the transformative power of higher education and puts a human face on America’s criminal justice crisis. It raises questions we urgently need to address: What is prison for? Who has access to educational opportunity? Who among us is capable of academic excellence? How can we have justice without redemption?

W&H: What drew you to this story?

LN: In 2012 producer Sarah Botstein and I were introduced to BPI when we gave a lecture about our “Prohibition” series to BPI students at Eastern NY State Correctional Facility. The following year, with a friend who is a professor at Columbia University, I had the opportunity to teach an eight-week seminar about documentary and history to BPI students at the same prison, and got to know a great deal more about the program.

Being in the classroom with such talented, ambitious students was beyond challenging. They are focused, serious-minded, disciplined, thorough, and they ask sophisticated and profound questions. This experience taught us a lot about the academic rigor of the program, and we also got to know some of the BPI students who ultimately ended up in our film.

From the very beginning, Sarah and I knew this film had to be told through the BPI students’ eyes, in their voices. There are nearly 2.2 million men and women behind bars, and we believe their stories need to be told, and their voices need to be heard.

W&H: What do you want people to think about when they are leaving the theater?

LN: First and foremost, the transformative power of education, and the humanity of incarcerated men and women. And then, the urgent question: who has been given access to education, and what are the ramifications for American society? Lastly, the impact of mass incarceration — which disproportionately affects communities of color and is the tragic result of a failed, broken, unjust system.

Here are some data points we share in the film: America spends an astonishing $80 billion on incarceration annually. Every year, more than 600,000 men and women are released from prison, and within three years, nearly half are back behind bars.

Higher education, as one of the students says in the film, “creates civic beings.” It promotes human dignity, enhances public safety, and dramatically reduces recidivism.

In the past 20 years, more than 500 BPI alumni have been released from prison, and fewer than four percent have gone back. But only a tiny fraction of the more than two million incarcerated men and women currently have access to college programs. So, above all, Sarah and I hope that the film opens viewers’ minds and promotes a civil, fact-based conversation about education and justice.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

LN: For me and Sarah, as well as our crew, filming for more than 50 days inside maximum security prisons over a four-year period was a huge technical, logistical, and creative challenge. And then, having collected 400 hours of footage, we had to shape, organize, and distill it into a four-hour film.

We had the great privilege of working with our terrific editor, Tricia Reidy, and assistant editor, Chase Horton, but it was a daunting process, to say the least.

Before this project, we had mostly worked on historical documentaries, with timelines and story arcs already built in, and we had relied on a third person narrator to set up, explain, contextualize. But with “College Behind Bars,” no narrator! We worked exclusively with vérité footage and the BPI students’ voices to tell the story. We were all on a huge learning curve, to put it mildly.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

LN: We received a small R&D grant from PBS and were able to shoot enough material to produce a trailer, and then we kept filming — and kept fundraising — over the following four years. In addition to a major production grant from PBS, our funders include the National Endowment for the Humanities, Ford Foundation/JustFilms, members of the Better Angels Society, and a number of generous individuals.

W&H: What inspired you to become a filmmaker?

LN: I fell in love with 20th-century documentary photography – Lewis Hine, Walker Evans, Helen Levitt, Robert Frank, Andre Kertesz, Lisette Model, Robert Capa – in college, and have been fascinated by human beings’ relationship to the camera’s eye ever since.

I was greatly inspired by several epic PBS documentary series of the early 1980s such as “Eyes on the Prize” and Stanley Karnow’s “Vietnam,” transfixed by the raw, visceral drama of Barbara Kopple’s “Harlan County U.S.A.,” and devastated and overwhelmed by Claude Lanzmann’s “Shoah.” Each of these masterpieces, in different ways, revealed the enormous power of documentary film.

It can be transcendent, almost euphoric, when great filmmakers let us see authentic experiences, memories, moments, and somehow reveal universal truths about what it means to be human.

W&H: What’s the best advice you’ve received?

LN: Don’t be afraid to admit what you don’t know, and always be prepared.

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

LN: Filmmaking is such an intensely collaborative enterprise, and as a director you have to recognize first of all that you can’t do it alone. You have to be able to work well with producers, editors, cinematographers, and in the case of documentaries, to connect deeply with the subjects of your film.

To do all of that, it’s essential to have a great partner/producer to collaborate with; in my case, that would be Sarah Botstein, whom I’ve had the privilege of working with for 20 years. We try hard to create a positive, open culture on our team so that everyone feels respected and heard, knows it’s okay to make mistakes, and on a creative level, we encourage risk-taking and experimentation. In the end, we believe this makes for a better film.

As a director, it’s essential to have a core vision, but also to be flexible and keep an open mind. You have to communicate clearly and directly, but as a woman — sadly, this is not news — we somehow have to do that without being perceived as bossy or strident. I have also been trying to get out of the terrible habit of apologizing for things that are not my fault!

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

LN: That’s a hard one – so many great filmmakers and so many great films. Can I offer two extraordinary documentaries?

Eleanor Coppola’s “Hearts of Darkness” for an honest, wrenching look at one of the iconic and troubled masterpieces of 20th-century cinema.

Jennie Livingston’s extraordinary landmark “Paris Is Burning” for shining a light on a hidden world, and treating her subjects with respect and compassion.

W&H: What differences have you noticed in the industry since the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements launched?

LN: There seems to be a much deeper awareness of inequity, harassment, bias, and greater willingness on the part of so many women to speak out. I am grateful for the conversation, but I am not sure there has been all that much systemic progress. We have a long, long way to go.