Orange is the New Black is a show about women, by women, based on the real experiences of one woman. It’s not perfect, but it’s good. In fact, it’s really, really good! It prominently features people too often marginalized by society — trans women, bisexual women, women of color — and guess what! They’re not just props on the show. They’re full people. This is progress, right?

Haha, nope, sorry. Not to Noah Berlatsky, a writer who sort of acknowledges how groundbreaking the show is, yet criticizes it for not having enough…dudes. (Yep). “There remains, however, one important group that the show barely, and inadequately, represents,” he recently wrote in The Atlantic. “That group is men.”

Specifically, dudes in prison. “This may seem like a silly complaint,” Berlatsky acknowledges, but continues writing anyway. He cites the staggering statistics on male incarceration in an attempt to make his point that OITNB isn’t fair to men:

Men are incarcerated at more than 10 times the rate of women. In 2012, there were 109,000 women in prison. That’s a high number — but it’s dwarfed by a male prison population that in 2012 reached just over 1,462,000. In 2011, men made up about 93 percent of prisoners.

That is true, and that is sad. The prison-industrial complex profits off the backs of men — mostly young black men. But there are plenty of critically acclaimed, popular shows and movies that explore this grim reality in detail: Oz, Prison Break, Shawshank Redemption, and The Wire, just to name a few. You can bet that there will be plenty more stories about these men, and there should be. But OITNB is not that story.

Berlatsky is upset that the male prisoners, who appear in two episodes of the thirteen-episode second season of OITNB as background characters, are stereotypically “super-predatory,” not full beings whose stories expose the injustices of an oppressive system; they don’t come off as the victims that they might very well be. Yet he conveniently glosses over the show’s treatment of its male supporting characters, all of whom are flawed but sympathetic to varying degrees, have personal lives, conflicting desires, and struggle with moral issues. It’s reasonable to assume that if a male prisoner were a major character, he’d be given a backstory, a personal life, and real wants and desires, too. But, again: male prisoners aren’t the focus of this show!

From this misguided observation, Berlatsky comes to the galling conclusion that the entire show is making a “stereotypically gendered” statement about “who can be a victim and who can’t” and therefore “remains trapped by gender preconceptions that aren’t path-breaking at all.” He argues that the female inmates gain our sympathies because they are 1) women, and 2) have emotional stories that revolve around love rather than stories that expose systematic oppression (because, duh, women are all love-sick puppies!).

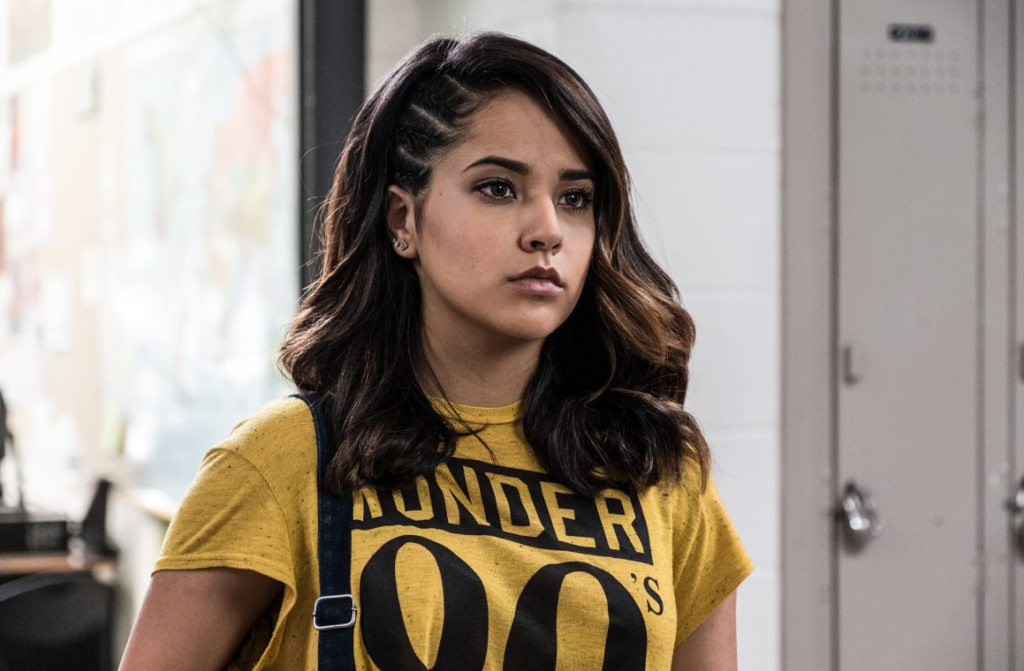

But on the show I watched, I saw plenty of minority women whose major crime was sadly just being born on the wrong side of the tracks, like Taystee (Danielle Brooks), failed by the foster-care system and placed with a drug-dealing sociopath, or Mendoza (Selenis Leyva), who had virtually no resources as a battered woman in a modest Latino community. I saw Red (Kate Mulgrew), an immigrant who became a pawn of the Russian mafia, and Pennsatucky (Taryn Manning), a poor white woman who was essentially sentenced as soon as meth found her. You can bet that pretty rich white ladies wouldn’t have had to make the sorts of decisions these women did (Piper certainly didn’t!). I also saw plenty of characters who illustrated that women can be abusers, like the murderous sociopath Vee (Lorraine Toussaint), predatory Boo (Lea DeLarea), and sweet-seeming Morello (Yael Stone), the woman who repeatedly threatened and stalked a man.

Berlatsky thinks we see all of these ladies as completely “innocent victims” because they’re sympathetic women, but that’s exactly the sort of sexism this show counteracts. Within the prison system, all things equal, a woman is more likely to receive a shorter sentence for the same crime that a man is. In Litchfield, we see that these women are tough, they can fend for themselves, they can be violent, they are dangerous, they are cut-throat. In fact, it’s their backstories that remind us that these women are human and capable of change (minus Vee), some for the better and some for the worse. Many of these women become sympathetic, to varying degrees, not because they each suffer from “a tragic lack of love,” as Berlatsky claims, but because we can see them for more than their crimes, and how they change in a system that clearly doesn’t care about them. It’s the kind of empathy we should have for all prisoners, not just men.

OITNB isn’t a documentary about prison life in America. It is not about to upend every stereotype we have about the prison population, which, yes, is mostly men. It is a drama meant to depict the stories of a few marginalized women we rarely see in mainstream media, give them voices, and let them speak. It does a pretty damn good job at that.