“Behind the image of the nondescript young mother, I can’t help but remember a woman secretly tormented by the need to write,” Nobel Laureate Annie Ernaux reflects in “The Super 8 Years” (“Les années Super-8”). How much viewers know about what’s behind an image is decided by the person holding the camera – in the case of “The Super 8 Years” that cameraperson was often Ernaux’s ex-husband, Philippe Ernaux. An image can withhold more than it reveals, wordlessly triggering the curiosity and even bewilderment of its viewer, and we see Ernaux playing with this narrative control in her autobiographical film, weaving a personal and family retrospective that is made more confessional and vulnerable by what’s not on screen.

In “The Super 8 Years,” co-directed with son David Ernaux-Briot, “The Years” author takes viewers into the interstices between the image, the subject, the filmmaker, and the spectator, retracing the decades of home video footage that documents the gestation of her writing career alongside duties of motherhood and marriage. We see how the seeds of Ernaux’s body of novels and memoirs, which center on the lived experiences of women during 1960s France and onwards, were sowed during these years. Ernaux, whose on-camera appearances are seldom and fleeting, reveals the promise she made to herself in her 20s: “I will write to avenge my people,” she quotes a diary entry in which she vows to redeem the working class in an elitist society.

Whether professional or recreational, filmmaking is a luxury. Few are afforded the privilege to document the most pivotal moments of their lives and even fewer are able to do so in long-form as the Ernaux family have. The camera has always been a prized possession of their household, especially to the writer, whose blue-collar childhood differs radically from that of her two sons. “Amid the flood of goods that one could acquire in the ‘70s, for us the camera was the ultimate desired object, much more than a dishwasher or a color TV,” Ernaux shares. “Film truly captured life and people, even if the films were silent.”

These silent vignettes in Ernaux’s video memoir are animated by the writer’s poetic and oftentimes solemn narrations of the most decisive chapters of her life: the upbringing of her children, the struggle to maintain her writerly pursuits, as well as the eventual dissolution of her marriage. From Christmas festivities to international holidays to mundane footage of living room decor, the motley scenes of “The Super 8 Years” exemplify the documentarian instinct of the Ernaux parents “to film what you would never see twice.” Amid the trappings of a nouveau riche lifestyle, Ernaux’s film dissects her threefold role as wife, mother, and artist, all three facets of her life that are apparently non-negotiable to her, but the archival footage also exposes how much her writing was eclipsed by mounting domestic obligations as the film, and the timeline in the film, progress.

“Poolside, I thought of the finished manuscript in my desk drawer,” Ernaux admits, narrating the footage of the writer swimming with her children during a summer holiday in Morocco. “I had hope that it would save me, but I didn’t know how, or from what.”

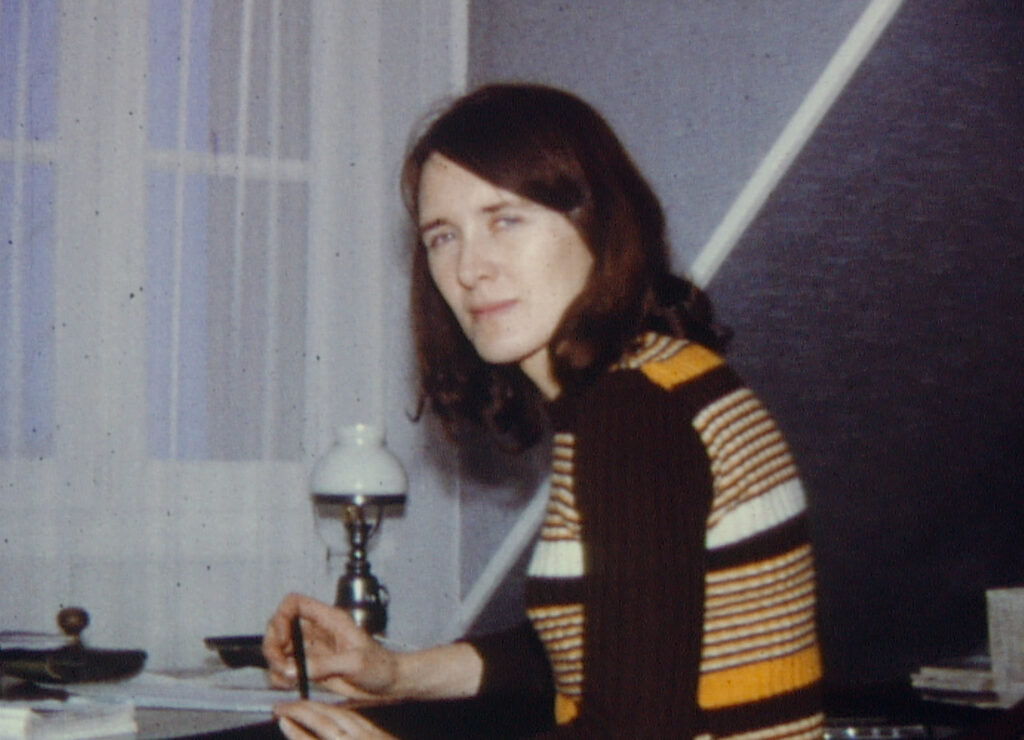

In addition to giving audiences an intimate look into the Ernaux family history, we are also privy to Ernaux’s retrospection of her youth, often referring to herself in the third person as if she were examining a foreign specimen, not herself. “She is 33 and doesn’t yet know that the manuscript sent by mail will be accepted by Gallimard and published as ‘Clean Out’ in the spring of 1974,” she narrates over one of the precious few on-screen appearances she makes in the film. Ernaux’s reflections often take on a detached and almost stoic tenor, perhaps she is able to examine these snapshots with objectivity thanks to the years that have passed. Or because she already knows the fate of the woman on screen.

“The woman in the image always seems to wonder why she’s there,” Ernaux says. She confesses that she “was a spectator” to the family’s yearly sojourns to the Aravis Range, during which Ernaux would be the “only one who didn’t ski” because she found a better holiday in the solitary activities of reading, writing, and admiring sunsets on the mountain range.

We see how Ernaux expertly manipulates the video footage in her storytelling, using the image-centric medium to articulate what she perhaps cannot with words on a page. We see footage of bullfighting from a summer holiday in Spain in the ‘80s. In the only portion of the film for which Ernaux is notably silent, audiences are forced to focus on the brutal choreography of the bullfighter provoking and then impaling the bull. In this prolonged scene of violent pursuit that ends with the bull getting dragged out of the stadium, limp and immobile, we can’t help but recall how Ernaux had earlier characterized the events of her life as “violent and red.” We can’t help but connect the power imbalance of the bullring to that of a household, where women are relegated to “the role of nurturer, silent manager, and steward,” as Ernaux reflects in her novel “A Frozen Woman.”

Ernaux’s meditations on the ceremony of watching films with her children and on the process of filmmaking itself illuminate the impetus of her life writing and her stories, many of which are derived from her own life. Why record our experiences at all, she seems to ask throughout the film. “What story was told in this parade of images with no sound but the crackle of the projector?” Ernaux asks. The objective, it seems, is already contained in the insights she gained in travelling back in time through the archives. “Words were needed to give meaning to this silent time, snippets of family life invisibly recorded inside the history of the era.”

“The Super 8 Years” is now in theaters and will be available on VOD December 20.