Artist and filmmaker Jane Pollard met her collaborative partner Iain Forsyth at Goldsmiths College in the early 1990s. After the duo earned early acclaim with A Rock ’N’ Roll Suicide (1998), a recreation of David Bowie’s final performance as Ziggy Stardust, they went on to create numerous video and sound installations.

Forsyth and Pollard have recently established an ongoing working relationship with Nick Cave, with their various projects together including producing the 3D audiobook of his recent novel and directing a series of 14 short films, Do you love me like I love you. Their first feature film, 20,000 Days on Earth, premiered at Sundance in January 2014, winning the Directing and Editing Awards. The film, backed by Film4, BFI, Corniche Pictures and Pulse Films, features Nick Cave alongside Kylie Minogue and Ray Winstone, with an original score by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis. (Press materials)

20,00 Days on Earth will premiere at the San Francisco International Film Festival on April 27.

Please give us your description of the film.

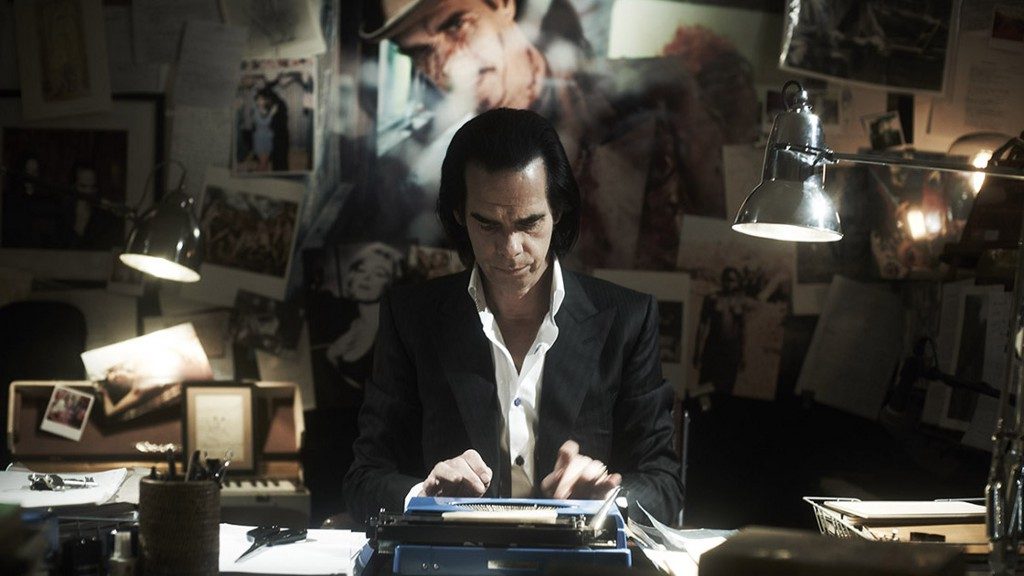

20,000 Days on Earth is an ode to creativity featuring the musician and cultural icon Nick Cave. The film fuses drama and reality by weaving the journey of a fictional day in the life of the rock star, with an intimate portrayal of his artistic process. The film examines what makes us who we are, and celebrates the transformative power of the creative spirit.

What made you write this story?

The methodology and creative vision on this project were borrowed completely from our practice as artists. This is our first feature film, and in many ways it found us, rather than the other way around.

We’ve worked on various projects with Nick over the last seven years or so. Over that time we’ve gotten to know him well and his trust in us has grown. None of us had any idea how this project might evolve when we began. When Nick first began writing this last album he called us and suggested he might be comfortable with us being around to film some of the process. We shot Nick and Warren starting to write together, and this led to us going into the studio with the Bad Seeds for ten days. We ended up shooting for about 16 hours a day, and we knew very quickly that what we were capturing were some extraordinary moments in Nick’s creative process. We’d all assumed the footage would end up forming some sort of promotional material for the record, but within a couple of days of arriving in France we instinctively knew that what we were shooting had to form the starting point for a film.

So we began to dream up ideas of what that film might be. Nick loaned us the notebooks he had been writing in and inside we found these disparate phrases that instantly sparked ideas that excited us. A big one was finding a calculation that worked out that Nick had been alive for exactly 20,000 days on the day they began recording the album. We were struck by the phrase “20,000 days on earth,” and began to work with the idea of what makes us who we are and what we do with our time on earth. The phrase eventually spawned the opening line of the film and was the basis for our idea to develop a structure for the film around a fictional narrative of Nick’s 20,000th day.

What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

The film couldn’t be a vanity project — that was a warning sign in all our heads, including Nick’s. He was very hesitant about undertaking this. He’s suspicious of biographies and celebrity documentaries, as they can appear self-serving. The challenge was how to approach things from a different way but make sure the ideas were strong, original, and still fundamentally accessible.

Our film is not a solemn, deferential portrait of an acclaimed musician. Instead, we focused on probing universal themes, including mortality, our time on earth and how we spend that time. We use wit and humor to deflect and deflate any hint of pomposity. We believe you can have a tremendously moving or inspirational film and still have moments that are raucously funny. It’s not a slight thing to be able to make people laugh. It’s an incredible thing. The audience gets to shuffle, become active and then reset a bit, when there’s humor there. It refocuses your mind and gets it ready to take on something else.

What advice do you have for other female directors?

I’ve worked as one half of a male/female collaboration for twenty years now, we never work alone, so I don’t particularly see myself as a female filmmaker. The only thing I want to be is a good filmmaker. The single piece of advice I go back to again and again is: Set your ambitions as high and far as possible — reach for the stars! Then, be prepared to fail, but know you have tried as hard as you possibly could. What matters is that when you fail, next time you fail better.

What’s the biggest misconception about you and your work?

We’ve made a film that seems to be incredibly difficult to describe, but very easy to watch! It’s a documentary and a music film, so people naturally have preconceptions, many of which aren’t true. They’re expecting maybe a concert film, or a behind-the-scenes look at the life of a rock star, something biographical that tells the story of a life. None of those things are what we were trying to do with this film. Once people see it, they completely get that, but it can be tough to explain. But our film hasn’t been released yet, so maybe my answer will be different in a few months!

Do you have any thoughts on what are the biggest challenges and/or opportunities for the future with the changing distribution mechanisms for films?

It feels like the best attitude is to not fear change, yet to stand firm on where value lies and to protect it.

Name your favorite women-directed film and why.

Lynne Ramsay’s Morvern Callar — a ballsy, brilliant and bleak version of Alan Warner’s masterpiece.