Julie Bertuccelli is the daughter of filmmaker Jean-Louis Bertuccelli. She worked as an assistant director to several well-known filmmakers before helming several documentaries for television. Her debut feature, Since Otar Left (2004), won the Cannes Film Festival’s Grand Jury Prize at Critics’ Week and the Grand Golden Rail, as well as the Cesar Award for Best First Work of Fiction, among other awards. Her next film, The Tree (2010), was nominated for several Cesar Awards and a number of major international film-festival and film-institute prizes. (Press materials)

School of Babel premiered at the San Francisco International Film Festival on April 27.

Please give us your description of the film.

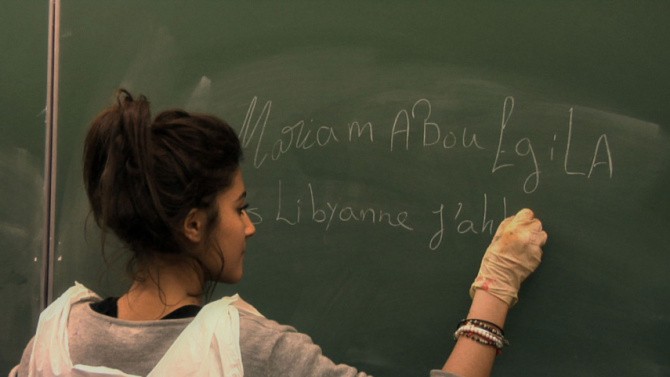

It’s a documentary. [My subjects] are Irish, Senegalese, Brazilian, Moroccan, Chinese: 24 students, 24 nationalities. They are between 11- and 15-years-old and have just arrived in France. For a year they will be all together in the same [language and cultural] adaptation class at a Parisian secondary school. In this multicultural arena, we see the innocence, the enthusiasm, and the inner turmoil of these teenagers who, caught in the midst of starting out on a new life, question our preconceived ideas and give us hope for a better future.

What drew you to this story?

I discovered adaptation classes when I was chairing a film jury a few years ago. There was something fascinating about those classes. It was a patchwork of so many nationalities and personal paths, yet sharing a common goal: to learn French and try to fit in a place they don’t belong. “A place they don’t belong”: this was the idea that struck me the most. When I was their age, I had lived in the same Paris apartment since I was born and I had some pretty fixed and well-rooted landmarks.

I wanted to get closer to these children, and the idea to film them became obvious. Very early on, I realized that I had to immerse myself among them for quite a while in order to understand what their life was about. For a year, then, I followed the daily routine of an adaptation class in a Parisian secondary school. I wanted to convey the turmoil that exile represents, especially at this key age, when childhood is close to an end. I wanted to know more about what they’d left behind — their culture, their beliefs, their memories, their hopes, as well as disillusions. How do they adjust to their new lives in France? What is their family situation? What is modeling their lives and imagination as teenagers? How do they feel about the integration that is expected from them, especially as they are simultaneously building an identity for themselves?

What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

As always, when you make a documentary, the most difficult thing is to be there at the right moment and at the right place with your camera, and trust in your film, when nothing happens! And be yourself and trust in your intuition and choices.

What advice do you have for other female directors?

Be yourself, and don’t be afraid when you doubt or are not sure of yourself, even in front of men, because it’s also our strength to be instinctive, sometimes fragile, and not pretentious.

What’s the biggest misconception about you and your work?

I don’t know! Maybe people think I don’t make enough films, not quite one each year, because of my three children. In fact, I’m not in a hurry to tell stories. It comes when it comes. I wait for the desire to become very strong and extremely necessary. I make each one as it will be the last one.

Name your favorite women-directed film and why.

Barbara Loden is unique and wonderful. I always think about Wanda, which touched me so much. And of course the great Jane Campion with all her films, all masterpieces — and a part of her soul.