Amanda Kernell has directed a number of shorts, including “Stoerre Vaerie,” or, “Northern Great Mountain,” which premiered at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival and won the Best Swedish Short Audience Award at the Göteborg International Film Festival. “Sami Blood” is her debut feature.

“Sami Blood” premiered at the 2017 Sundance Film Festival on January 20.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

AK: “Sami Blood” is declaration of love to an older generation — to those who left reindeer herding and the Sámi way of living, and also to those who stayed — told entirely from a young girl’s perspective.

I wanted to make a film where we see the Sámi society from within and experience this dark part of Swedish colonial history in a physical way. I wanted to make a real coming-of-age story, a film with yoik (chanting) and blood.

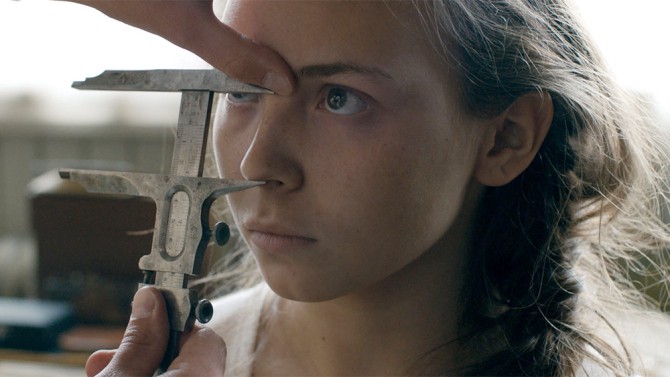

The film is about a young girl named Elle Marja who is fourteen and soon to take over the traditional reindeer herding in her family. Elle dreams of another life, and after being exposed to racist practices at school against the Sámi people, she finds it unbearable to remain in her current situation. She decides to escape and pass herself off as Swedish, and she makes the difficult decision to break all ties with her family and the culture she comes from.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

AK: There are elders in my family who strongly reject Sámi people — the indigenous people of Northern Europe — even though they are Sámi themselves.

They grew up in the mountains in reindeer herding families only speaking Sámi language, [but they] went to the Sámi boarding schools where only Swedish language was allowed. Now, they go by other names and claim they are Swedish and haven’t spoken to their siblings since the ’60s. This isn’t just in my family — it’s a large part of this generation.

I’ve always wondered why these people chose to become someone else. And can you really become someone else? What happens when you cut all ties with your past, your culture, and your history?

W&H: What do you want people to think about when they are leaving the theater?

AK: I hope people watching the film think about where they belong, blood ties and heritage, shame, and the radical decisions people take in their lives.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

AK: There are a lot of challenges shooting a film like this on location by the polar circle. You have to consider mountain weather, mosquitoes, dogs, a lot of reindeer on set, and a ton of children, non-professional actors, and elders.

There are a lot of difficult scenes — stunts with reindeer and blood, as well as fights and emotionally challenging scenes. Another aspect that was a personal challenge was the language spoken in the film.

Half of the dialogue is in South Sámi — one of the world’s most threatened languages with only 500 native speakers. Finding two real sisters for the main characters among these 500 speakers was a huge challenge, especially as I wanted to find two young girls who were something special.

I was extremely fortunate to have found Lene Cecilia Sparrok and her sister Mia Sparrok — they’re very talented and exciting to watch, delivering some of the best acting I’ve ever seen. So, what could have been a challenge working with all these South Sámi-speaking non-actors with no experience turned out to be a blessing.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

AK: In the Nordic countries we have state funded film institutes, and we were lucky to be funded by many of them: the Swedish Film Institute, the Danish Film Institute, the International Sámi Film Institute, Eurimages, Norwegian film funds, other smaller funds. It is also a co-production with Swedish Television.

W&H: What does it mean for you to have your film play at Sundance?

AK: First of all, it’s a great honor to be invited. It has kind of been surreal with all the attention the film has gotten after premiering in Venice and then Toronto and all the awards, and now Sundance.

I’m very grateful and proud of all the work the cast and crew have put into this film. I’m so happy that people can see it around the world and seem to appreciate and connect to it, both as a story and in reference to the craftsmanship and artistic work.

On a personal level, having a film at Sundance means exposure for me and for the film in the U.S., and that means a lot as well. I would love to able to make movies in America as well as in Europe, so it’s a great opportunity to be able to come attend the festival and meet people.

On an even more personal level, I’m also excited that Sundance is arranging a community outreach screening for the Native community, and it means a lot to be able to be there and talk to people with experiences that may be similar to mine and my families,’ and the story in this film.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

AK: The best advice: To carry everyone’s shame as a director, and release your actors of their shame and fear of failure.

I think it’s important to create a space where everyone can dare to try new things and push boundaries. It’s an important task as director to try to eliminate shame when it’s possible, since it blocks your creativity. That’s why I also try to surround myself with people who, in turn, take away my own shame and fears.

To be able to make something truly original and interesting, we must be able to make brave decisions.

The worst advice: Its probably something at film school. I learned a lot, and I’m very happy that I attended the program at the National Film School of Denmark. However, every day that I attended, the teachers tried to tell us students how to make films, and though most of it was useful, there were of course some things said that I didn’t agree with. One piece of advice received from a teacher was, “Every good movie starts with the promise of sex with a beautiful woman.”

Personally, I’m not a fan of this advice, and I also think it’s dangerous to educate everyone to make films in the exact same way regardless.

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

AK: Be honest. Be brave. That’s equally applicable for both female and male filmmakers, but that’s the advice I constantly have to remind myself of — and it goes for every step of the process.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

AK: I think it’s “Ratcatcher” by Lynne Ramsay.

I’ve used “Ratcatcher” a lot as inspiration for mise en scène, photography and framing, as well as storytelling. It’s my kind of film — it’s violent, funny, touching, and true, and it gives you images that you will never forget.

W&H: Have you seen opportunities for women filmmakers increase over the last year due to the increased attention paid to the issue? If someone asked you what you thought needed to be done to get women more opportunities to direct, what would be your answer?

AK: I’ve been in production almost non-stop for the last couple of years and therefore completely absorbed in making these films, so I’m not sure whether I have seen an increase or not. I’ve read the statistics for the Swedish and Danish and the US industry of course, but I don’t know more than that.

We all have different tastes, and I think that a greater diversity among decision-makers would be beneficial for everyone because it would cater to the different tastes of all people — and it would also be beneficial for female directors and for women in the industry.

To get there, I don’t think we can just sit and wait for it to happen, though. I think that we all have to commit to getting out of our comfort zone and making braver decisions. That goes for me as a director as well.