Debbie Lum is an award-winning filmmaker whose projects give voice to the Asian American experience and other unsung stories. “Seeking Asian Female,” her feature-length directing debut, premiered at SXSW, aired on PBS’ “Independent Lens,” and won numerous awards, including Best of Fest (Silverdocs), Best Feature Documentary (CAAMFest), and Outstanding Director (Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival). Lum previously worked as a documentary editor. Her editing credits include “A.K.A. Don Bonus,” “Kelly Loves Tony,” and “To You Sweetheart, Aloha.” She has also written and directed several short comedies, including “Chinese Beauty,” “One April Morning,” and “A Great Deal!”

“Try Harder!” is screening at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival, which is taking place online and in person via Satellite Screens January 28-February 3.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

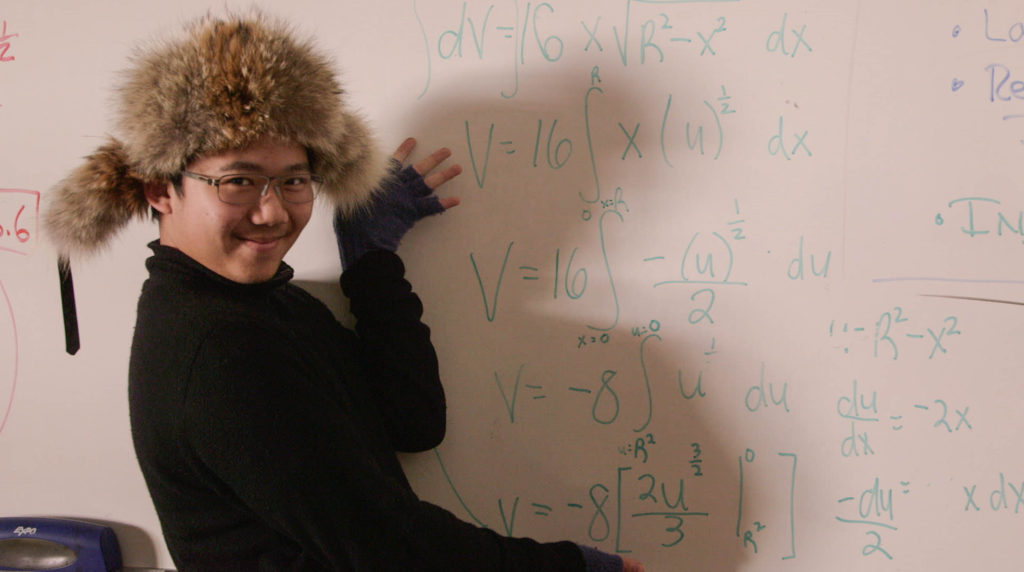

DL: “Try Harder!” follows five students at Lowell High School in San Francisco, California as they try to get into an elite college of their dreams. Lowell High School is one of the top public high schools in the SF Bay Area. It has selective admissions based academic performance and is a competitive, high-achieving, predominantly Asian American high school.

In a world where popularity is measured by the highest GPA, and immigrant dreams mix with persistent parental pressure, the story follows the students’ journey with humor and heart as they confront impossible odds. Will their hard work pay off? What happens if they fail?

“Try Harder!” is a student-centric and poignant coming-of-age story that gives an intimate window into what young college hopefuls face today.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

DL: The students of Lowell High School captured my heart. At first, I thought I would explore the topic of elite college admissions through the perspective of mothers, and specifically the stereotype of Asian American “tiger mothers” who push hard for their children’s academic achievement by any means necessary.

I have three kids, and the oldest at the time was starting preschool. Around me, parents, mostly moms, were stressing out about what they could do to set their three-year old on a path that would end in Harvard. The Harvard lawsuit alleging that Asian Americans were being discriminated against and articles about high-priced college counselors admonishing Asian American students to try not to appear Asian in order to have a better chance of getting into college were in the media.

I got seed money to make a film called “My Tiger Mom” from ITVS. We filmed mothers, principals, psychologists, and we wanted to talk to the students themselves. We heard about a program at Lowell High School where kids as young as 14 did graduate-level medical research at the world-renowned UCSF medical labs. Once I landed at Lowell High School and the students, faculty, and administration opened their doors to us, we couldn’t let a gift horse get away and decided to switch gears and capture the students story.

In all the headlines-grabbing reports on the insanity of the college admissions process, the students who are at the heart of the story seem to be the last ones given a voice. Lowell High School, a San Francisco institution and the oldest public high school west of the Mississippi River, had never had a feature-length documentary about it. I couldn’t help think that, perhaps because Lowell has had a large or predominantly Asian American student body for decades, this might have something to do with it.

I went to a high school in America’s heartland, more reminiscent of “The Breakfast Club,” where being Asian American meant being either an outcast or invisible. I was fascinated by a high school universe where being Asian American is the norm.

I’ve dedicated my filmmaking career to telling Asian American stories. I’m drawn to the untold, authentic stories, and this one really resonated for me.

W&H: What do you want people to think about after they watch the film?

DL: “Try Harder!” is a journey that shows audiences what it feels like to finish the last year of high school and, against impossible odds, try to achieve one’s high school dreams, sometimes succeeding but often failing. I’d like students, parents, educators, and audiences in general to get through to the other side of this journey.

High school has changed in the last decade, and today academic pressure is the leading cause of stress in teens over “fitting in” or “looking good.” Getting into a brand-name college can feel like a life or death matter to students — and perhaps even more so to their parents. Success through education has been foundational in our society, and particularly in the Asian American community, where educational achievement is the lifeblood coursing through our communities veins.

For immigrants who have historically been in survival mode, striving to succeed through education has been the means and at all costs, and there has been a lot of sacrifice. In the Bay Area, many high school principals are on suicide watch and many students finish high school feeling cynical that trying hard isn’t enough.

For our community and society at large, we often strive with little time for reflection. I hope “Try Harder!” can be a mirror that allows viewers to reflect on how this process has impacted who we are, why we strive, and our relationships between young people and parents.

I hope audiences walk away knowing that the students of Lowell High School are much more than test scores and high-ranking GPAs. I’d like the human factor in the “college application industrial complex” to come to the fore.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

DL: Lowell High School is the largest public high school in San Francisco. We were very lucky to have the principal at the time, Andrew Ishibashi, understand what we were trying to do by shining a light on the students of Lowell in a film, and to have the support of our students’ parents.

Because we didn’t know how our subjects’ college admissions journey would turn out, we followed more students than we could put into the film. It was hard to cut those students’ narratives out. By the same token, we ended up profiling five students, a large number for a multi-character film. Three of our students are Asian American, one is biracial African American, and another is white.

Along the way, some suggested we cut out two of our Asian American characters. I felt strongly that this was an injustice to the story of a high school that has been predominantly Asian American and the time was overripe for Asian Americans to occupy center stage as protagonists in the story. Telling Asian American stories — stories about marginalized communities that sometimes go counter to the mainstream — always present challenges to how we tell stories. It required deft editing and lots of patience to do justice to the students in our film and their stories.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

DL: Like the students in our film, we applied to public television funding knowing the odds were against us. We received Open Call funding from ITVS and were told that it was more selective than getting into Harvard. Sometimes filmmakers apply three to five times or more before being funded, so we considered ourselves fortunate be selected the second time around.

At that point, we had received a development grant from California Humanities and a production grant from the Center for Asian American Media, who are wonderful partners to work with. That funding allowed us to shoot on a slim budget. We were about to launch a Kickstarter campaign when we got greenlit from ITVS, who gave us completion funding for post.

Of course, we went over-budget during post and then were lucky enough to have XTR come on to help us finish our theatrical version and get us Sundance.

W&H: What inspired you to become a filmmaker?

DL: Movies so informed my identity growing up that, like many in my generation, it just seemed like a natural thing one would do. I grew up behind the Creve Coeur Cinema in St. Louis, Missouri, in the “Star Wars” generation, the first generation of blockbuster movies. We didn’t have 100’s of channels of television or TikTok, Kindle, and pushed news feeds.

Cinema was an immersive experience and my father who grew up in Honolulu, Hawaii took us to the Oscar contenders, old Hong Kong martial arts films, Spielberg blockbusters, and age-inappropriate art house films like “Ran” or “Picnic at Hanging Rock” that burned into my consciousness and inhabited my dreams.

My mom, who grew up in New York city and rebelled from her traditional Chinese parents, dreamed that her children would be artists and curated avant-garde cinema for her an art collective she ran. It was the ’70s, and it was a less materialistic time. The adults around me feel that art mattered as much as profit.

An uncle took us to a screening a film by Wayne Wang called “Chan is Missing,” and Wang’s wife, Cora Miao, was there. I remember thinking she was the most beautiful person I had ever seen in real life. I never thought it would take another 40 years for an Asian American film to become a blockbuster success. Let’s hope there are many more.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

DL: My mom has given me all the best advice throughout my life, and also possibly the one, perhaps, worst advice anyone could give, as mothers sometimes do. We are full of contradictions. My mother always says, “If there’s one way, there are 10,000 ways,” and that any great problem could be solved by giving someone attention.

I’ve listened to this advice many times while making documentaries, especially in production. When I was filming my last film, “Seeking Asian Female,” I was always at the beck and call of my subjects, as I filmed two strangers who did not speak the same language, creating a marriage from scratch. Invariably something amazing would happen and I’d scramble to get there as fast as I could. But if I didn’t get there in time or couldn’t negotiate a location release in advance, I’d have the sense that I missed the scene and feel regret.

My mentor, Spencer Nakasako, would remind me that there will always be another filming opportunity and it might be a better one the next time and invariable this would be true. Taking the long view, as my mother always advised, is best.

W&H: What advice do you have for other women directors?

DL: We make art because we have no choice. We are passionate, seeking out the truths that we feel compelled to tell. But it’s easy to doubt yourself — so many of us have been trained to question, and to question ourselves. It’s what makes us empathetic to others to those whose stories we tell.

But the flip side of that is self-doubt. Worried that you are being too egotistical, not wanting to “mansplain,” but perhaps the hardest thing to do is to take yourself seriously.

Find a fearless producer who understands that and will support you even when you must question yourself. I think when you take yourself seriously, test your passions, believe in yourself, and still question yourself, you’ll find an equilibrium of truth. I always tell my kids sometimes takes it takes a long time, but the truth will come out. The truth will set you free.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

DL: It’s always hard to do this. One of my favorite woman-directed films is “The Piano” by Jane Campion. Everything about it goes beyond words, my explanation included. All that makes up silence, that which cannot be articulated in words alone, the contradictions in human desire, and the film’s themes are so beautifully expressed in a way that only a film with a woman protagonist and woman director could do.

W&H: How are you adjusting to life during the COVID-19 pandemic? Are you keeping creative, and if so, how?

DL: I feel fortunate to live in San Francisco, a city where science is foundational, and nine out of ten people wear masks and respect social distancing to stop COVID. That said, our public schools went virtual in March of last year. Adjusting to becoming the ad hoc dean and substitute teacher to my three kids in three different Zoom schools brought my doc-making to a halt at first.

For a spell, I pivoted to developing a narrative screenplay just to remain hopeful. Our family re-calibrated, my husband stopped traveling for work, this school year has been an improvement, and everyone rallied around helping their mom push out “Try Harder!”

Needing more support, I brought on a new team, all working remotely from Portland (editor, Andrew Gersh) to Oakland (producer, Nico Opper) to New York (EP, Jean Tsien), and even down the street in San Francisco (producer/cinematographer, Lou Nakasako). It takes a village and I am grateful that my husband and three kids have made it the priority in our home/school/office to finish “Try Harder!”

W&H: The film industry has a long history of underrepresenting people of color onscreen and behind the scenes and reinforcing — and creating — negative stereotypes. What actions do you think need to be taken to make Hollywood and/or the doc world more inclusive?

DL: We need POC filmmakers at the center — as executives, writers, producers, directors, and studio heads. Movies are powerful and curating content that is authentic and anti-racist would help reset old standards. Taking a chance, taking risks, not just repeating what we know. Mentorship.