Jennifer M. Kroot’s directorial credits include “To Be Takei” and “It Came From Kuchar.” She has received grants from the Andy Warhol Foundation, Creative Work Fund, Frameline, the Pacific Pioneer Fund, California Civil Liberties Public Education Program, and the Fleishhacker Foundation.

“The Untold Tales of Armistead Maupin” will premiere at the 2017 SXSW Film Festival on March 11.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

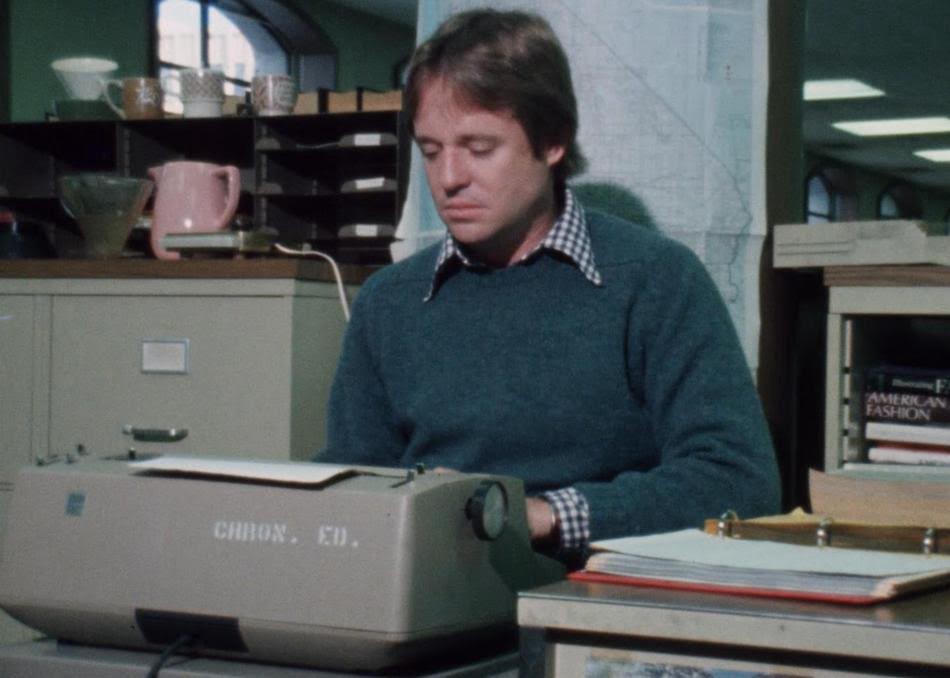

JK: “The Untold Tales of Armistead Maupin” is a documentary portrait of one of my favorite writers, Armistead Maupin. He is best known for his “Tales of the City” series of novels that started as a daily column in the San Francisco Chronicle in 1976.

This film explores Maupin’s inclusive — but not necessarily politically correct — writing, and it examines his personal transformation from conservative son of the Old South into an openhearted gay rights pioneer and beloved storyteller.

The film is visually rich with layers of archival footage of San Francisco in the ’70s and present day. Animation helps interweave the structure and many moods of the film. The film includes reflections from Maupin’s friends and colleagues, including Sir Ian McKellen, Laura Linney, Amy Tan, Neil Gaiman, and Olympia Dukakis.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

JK: I have been a fan of Maupin’s work since ’94, when the “Tales of the City” miniseries aired on PBS. I read the books then, and his vision of gay and straight people living together really resonated with my own experience as a young person in San Francisco. I had grown up in the bay area in the ’70s and ’80s, and I remember all the adults — like my parents — always talking about “Tales of the City” when it was a column in the SF Chronicle.

More recently, I read that Maupin had been vehemently conservative and even supported segregation when he was young. Jesse Helms was actually the first person to hire him for a writing job! I love the idea that someone could undergo such a huge personal transformation — from being conservative and closeted to coming out with such an open heart and sharing it with others through storytelling.

I also love Maupin’s idea of the “logical family,” as opposed to the biological family. Since his blood family was so conservative, he realized that he needed to create a family of like-minded people who could support him for who he is.

I actually have a great biological family, but I have known so many people who have had serious issues with their families because of their sexuality or progressive beliefs. It seems like this idea of the “logical family” feels very relevant right now, especially when our country — or maybe even the world — is becoming so increasingly divisive.

W&H: What do you want people to think about when they are leaving the theater?

JK: I hope that they will be inspired by the idea that by expressing your authentic self, you can find your place in the world with the right people. I would hope that people will realize that they are not alone in having conflicts with their own families, and be touched by Maupin’s description of finding a “logical family.”

Maupin came out in a unique way by writing his voice into one of his fictional characters, penning a piece as part of “Tales of the City.” It was called “Michael’s Letter to Mama,” and Maupin immediately knew that his parents would understand that the letter was directed at them. The letter has gone on to inspire a countless number of LGBTQ people to write to their own families and come out.

I hope that people who want to come out to their parents find support and comfort in “Letter to Mama.” Although the letter was written over 40 years ago, it still remains so incredibly relevant.

As a San Franciscan, I hope that people will see how beautiful my city is and always has been.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

JK: Editing is the most challenging part of filmmaking, but also the most satisfying. It’s always difficult to build a structure for a film. I prefer to not tell a story in linear time — it seems like a restriction that we have in our real lives, but it’s not necessary to follow that when making a movie. There’s a freedom to move any direction in time in film.

I always come back to the amazing structure of “Slaughterhouse-Five” for inspiration.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

JK: Grants and donations.

Research philanthropists in your area, and find out which ones might be interested in supporting the type of work that you’re doing.

If you get a grant at a foundation, stay in touch, so that they remember you when you make more films and you can return for support.

W&H: What does it mean for you to have your film play at SXSW?

JK: It’s a tremendous honor to premiere the film at SXSW. I feel like the SXSW programmers appreciate more creative and quirkier films, which gives the festival an interesting edge.

SXSW is an amazing springboard to start off our festival run, and I expect that screening “The Untold Tales of Armistead Maupin” will be a great opportunity to showcase it to not only a festival audience, but hopefully a much bigger one after our festival run is completed.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

JK: The best advice is to always backup your footage on three hard drives! Make sure that they are new and good quality hard drives.

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

JK: Don’t pretend that you’re not female to try to fit in with predominantly male filmmakers.

I’ve noticed that women will often help each other out, so be nice to the women in film that you meet. You never know if they’ll become a programmer somewhere, recommend you to a distributor, or suggest you for a directing job. Sometimes people can feel more competitive with people who are similar to themselves — I think it comes from the reptilian brain. Try to get beyond that feeling.

Surprise people. Don’t be afraid to explore subject matter or styles that are not usually associated with women directors or filmmakers. There’s honestly nothing I hate more than “women’s films” or “romantic comedies” or “date movies.” I think it’s exciting when women explore sordid subjects, horror, comedy, camp, or experimental editing styles.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

JK: May I name three please?

“Paris Is Burning” by Jennie Livingston is one of my favorite films of all time. She gained the trust of a beautiful group of disenfranchised artists and gave a glorious portrayal of their world that is magical, entertaining, and also explores issues of race, class, gender identity, and sexual orientation. It’s really unlike any other film and speaks to people of all ages and backgrounds. Beautiful characters!

Julie Taymor’s “Titus” is also an incredible film. It’s a very theatrical, even campy film, and it’s so unusual for women to incorporate camp in their work. The visuals are completely over the top and insane. It’s also extremely violent, which is something else that isn’t often attributed to women. It’s a vivid, lush, horrifying, and kind of humorous experience. It’s the opposite of the stereotypical “women’s film.” Julie Taymor is amazing!

“Desperately Seeking Susan” by Susan Seidelman is another favorite. I have loved that film since I was a teenager. It’s the only movie that Madonna is good in, and it’s a really fun, silly story with wacky characters. I love the idea that a housewife from New Jersey gets a crush on the street urchin Madonna character. It’s well-written with lots of quirky details, and it captures what was actually cool about the ’80s.

W&H: There have been significant conversations over the last couple of years about increasing the amount of opportunities for women directors yet the numbers have not increased. Are you optimistic about the possibilities for change? Share any thoughts you might have on this topic.

JK: My answer is broader than filmmaking.

So many women that I know are deeply angry about the way that Hillary Clinton was treated in the election, and I feel like women in many different traditionally male-dominated careers are planning to work and fight harder than ever to succeed at those careers.

I have noticed that the word feminist has been reclaimed and no longer has the ugly connotations that it once did when I was young. I know lots of young women who are happy to call themselves feminists these days. I think that’s a great sign for all of us.

I am both optimistic and realistic about opportunities for women. There are many times at film events when people assume that I must be an actress or the girlfriend of someone in the film. It’s annoying and insulting of course, but it doesn’t bother me as much as it used to.

I can tell that people often underestimate me, and I honestly think it’s based on my gender, but it’s exciting to prove doubters wrong when you do succeed in making an acclaimed film.

I just try to do my best at the things that I’m driven to do.