Born in Inner Mongolia, China, Yuqi Kang was awarded the Paula Rhodes Memorial Award for Exceptional Achievement in Social Documentary Film upon graduating the School of Visual Arts in New York. Her documentary short “Last Days of Domino” premiered at DOC NYC, and was awarded Experimental Short Honor Mention. “A Little Wisdom” is Kang’s feature directorial debut.

“A Little Wisdom” will premiere at the 2018 SXSW Film Festival on March 10.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

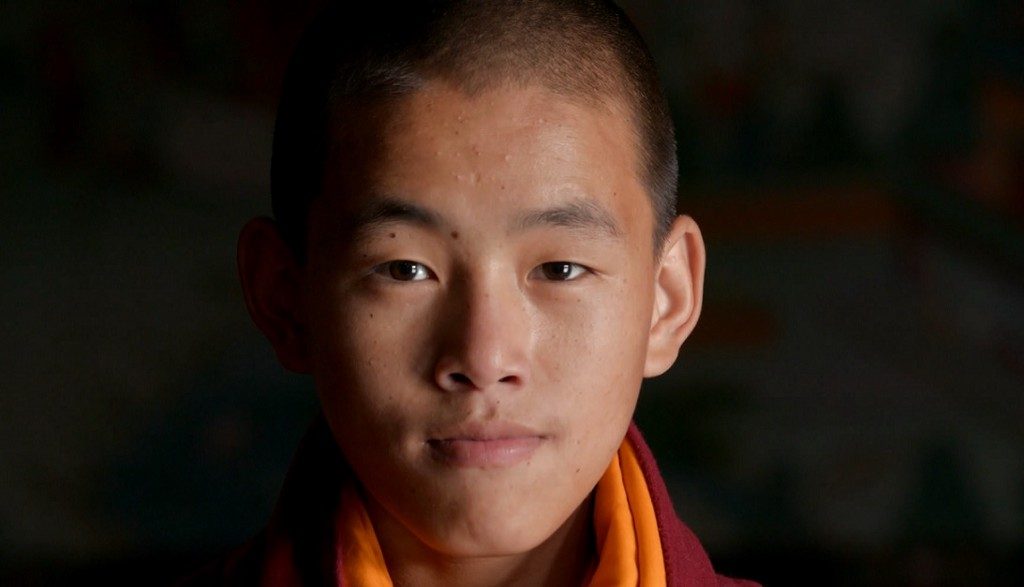

YK: My film is about childhood taking place inside a century-old Buddhist monastery in Lumbini, Nepal, the birthplace of Buddha. We follow the daily routine of the youngest novice, Hopakuli, and his older brother, Chorten, both left by their mother at the monastery. In the midst of the vast, untouched forests and sacred Buddhist pilgrimage site, the children let their natural fascination and longing for the world beyond Lumbini run wild.

Essentially, the story is universal: how children view the world and find happiness through simple life and the power of their imagination.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

YK: In the summer of 2014, I traveled to Lumbini and lived among the monks for six months. In the beginning, I proposed to make a documentary film on Buddhism; the monks instead offered for me to join them in their life and attend their daily practice. Over time, these little monks opened up to me. They become little brothers to me. I started to see another side of monastic life.

The young boys’ understanding of the world outside was influenced by TV, Facebook, and other kinds of stimuli despite being geographically isolated. They shared with me their doubts, fears of the future, innocent desires for puppy love, and even their favorite tree to climb on inside the enormous Lumbini Garden.

This experience with the monks shattered my previous romanticized understanding of monastic life as the popular media often portrays the monks as happy-go-lucky, and carefree.

Hopakuli in some way had a special bond with me, as I was also a very imaginative child and had difficulty fitting into groups at a young age. When he held onto my hand when I was about to leave Lumbini, I could only see a four-year-old child who was helplessly looking for affection and love. It was then I felt committed to creating work that delves into these kids’ lives.

W&H: What do you want people to think about when they are leaving the theater?

YK: There is a quote from one of my favorite works of literature, “The Little Prince:” “All grown-ups were once children… but only few of them remember it.” The experience of living with these children recalled my own memory as a child. I forgot that I was an adult when we were hunting for the monkey in the forest, chased by the wild pigs, and climbing on the trees.

On the other hand, I could also relate to their feelings of longing for their parents, and specially during those moments when the children expressed to me that they had forgotten how their mother looked, as I also grew up mostly apart from my parents.

I worked on crafting this film to be emotionally accessible to all, as we all were kids, and perhaps have dealt with similar or different problems to those these young monks confront.

The goal was to recreate a journey and the emotional connection I had with the subject for the audience. I hope the audience will see these children are not only monks but also children like every one of us, because monks are also real people with emotions just like us.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

YK: I think in documentaries, one of the biggest challenges is always gaining the trust from the filmed subjects. I remember at first when I proposed the idea of making the documentary that I was only granted permission to film their morning and evening practices twice. After that, I edited the footage from the prayer sessions, and showed it to the head monks as well as the children. All of them seemed to be fascinated by the camera, and the idea of filmmaking, so the monks invited me to teach the children classes during their free time.

Slowly, I was granted permission to film in the halls. I always carried the camera around but never filmed intensely. I wanted the monks to get familiar with me, and the camera.

I allowed Hopakuli and some of the boys to play with the camera and shoot their own films with it. Surprisingly, a lot of the children have a keen interest in filmmaking. They made some kung-fu films, and filmed some of their secret playing locations. They showed me their footage, and started sharing their stories.

Initially, I was told that the dining hall and the bedrooms were off limits but as I spent more time filming, and getting to know all the monks, these restrictions were relaxed. This was an exercise in building trust.

Eventually, I was being called the sister or the mother of these children. Most of the scenes in the film happened spontaneously as I was always around. It was then a matter of time until they forgot I was there with my camera. Then the challenge I was facing was how I was representing these children on screen. Do they fully understand the ramifications of being in this film? I thought a lot about my responsibility as a filmmaker. It is a [complicated issue and one that] I always need to carefully [consider.]

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

YK: I was enrolled in the Social Documentary Film Department at School of Visual Arts in New York when I started making the film. It was an incredibly supportive environment. As I shared my idea of the film in Nepal, two of my friends from school jumped on board and committed their time for the project without getting paid. I expected as a first-time director the chances of getting grants or funding was difficult.

I have always been able to maintain the budget within the range that I could be able to fund myself throughout the project. It required a lot of extensive researching, sincerity, and persistence in asking people’s support. At times, it was also difficult to balance my role as the director and the producer at the same time.

While I always wanted to make the best film possible, I also was restricted due to the budget. In the end, it was an incredibly rewarding experience. Not only did we complete the film with such a small budget but we also built lifelong relationships and partnerships with people who work in the same field.

W&H: What does it mean for you to have your film play at SXSW?

YK: SXSW is one of the most acclaimed film festivals in North America, and has showcased many new voices and emerging talents in the past. Being selected in the 2018 showcase was my greatest honor and a milestone very early in my career path. It has given the film a great deal of exposure but also brings myself as a filmmaker into the SXSW family along with countless talents, mentors, and film industry professionals.

I can’t be grateful enough to have been supported by SXSW and very much look forward to the screenings.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

YK: I was really lucky to have shown some of the previous footage, and the film idea, to my story consultant, Alan Berliner, very early on. I remember he emphasized only one thing to me — to use a tripod, and always be patient while filming to let the scene to play out. It ultimately helped to establish the style and pace of the film.

Throughout the year-long process of editing, I have received a lot of advice from great filmmakers, friends, and family. In some way, all of the advice has helped to shape the film. I don’t recall a worst piece of advice but I always kept reminding myself of the film I wanted to make — and always take all the advice with a grain of salt.

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

YK: There are a lot of great female directors from my graduate program such as our department chair, Maro Chermayeff, as well as my other instructors, Donna Shepherd and Deborah Dickson.

One of the most valuable pieces of advice I have learned from Maro is always to trust my own instinct as a director. The generous support from other female directors really helps me to get through the difficult and constantly self-doubting process of completing the film.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

YK: The first film that made me see a difference between a female director, and a male director was “Water Lilies,” made by the French director Céline Sciamma. The film is realistic and doesn’t have a dramatic plot. During one scene, one of the female leads digs out her crush’s trash, and after she investigates the contests, she finds a half-eaten apple. As the girl begins to eat the apple, my stomach felt a physical cringe. As the silent scene plays out on its own, the sense of desire was exploded on screen. Watching the film brings me right back to being an adolescent girl — the emotions feel so real and fresh.

Since then I began to pay attention to the directors after viewing films — surprisingly, most of the films that depicted emotions that I can relate to strongly as a female were all directed by woman directors.

I am really excited to be included in SXSW’s program — 60 percent of features screening in competition are by female filmmakers.

I hope in the future woman’s voice will be played equally in this industry.

W&H: Hollywood and the global film industry are in the midst of undergoing a major transformation. Many women — and some men — in the industry are speaking publicly about their experiences being assaulted and harassed. What are your thoughts on the #TimesUp movement and the push for equality in the film business?

YK: I feel really grateful to be a woman born in this day and age. Sexual assault and harassment doesn’t only happen in Hollywood — it’s a common occurrence that happens in all different countries and professions. I am profoundly inspired by the ones who speak to this matter and share their personal experience publicly on these matters.

The #TimesUp movement has also helped me to gain a lot of understanding and re-educate myself. I think it is very important and timely not only for Hollywood but also globally to address this issue, and for people to feel comfortable to speak out to prevent it from happening in the future.