The Normal Heart, Larry Kramer’s critically acclaimed play that was adapted for television in a film produced by HBO, is a dramatic archive of feeling about the profound atrocities of the AIDS crisis experienced during the epidemic inception in the 1980s, when no one knew what was going on.

The HBO film is superb, absolutely stunning in its ability to capture the humanity behind the chaos, while at the same time understanding that humanity is not infallible or fearless. The fear of those living through the epidemic is only surpassed by the pathos: it was only since Stonewall in 1969 that gay people felt a community-wide pride about being gay, and the culture around the AIDS crisis made all gay people question this relatively new form of confident self-expression, which primarily manifested itself in an ethics of sex positivity.

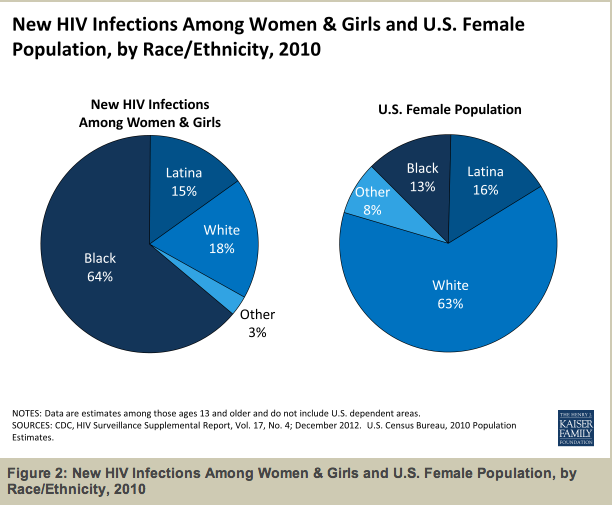

According to recent statistics released by the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, women account for 20% of HIV diagnoses, with a majority of that percentage being straight women and/or women of color. In 2010, 84% of women infected were done so by heterosexual sex, with over 60% of those women living with HIV being black.

It is an egregious error to believe that HIV has only ever been a gay man’s disease. The “gay cancer,” as it was originally called, actually did not discriminate in terms of whom it infected — men or women, straight or gay. Earlier this year, there was even a recent report of a lesbian infecting her female partner in what the media called an “extremely rare case.”

Why are women erased from this history, particularly, in cinematic portrayals of the AIDS crisis?

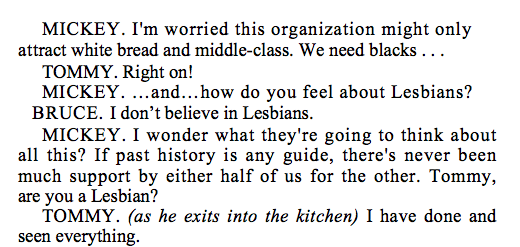

In the Samuel French Acting Edition of The Normal Heart, lesbians are mentioned in one scene:

This schism is portrayed in the HBO version, too. There is no mention of lesbians, save one scene, in which a woman enters the offices of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) and cries about the loss of her best friend, a gay man named Harvey. She says that she wants to help the GMHC in any way possible, “even though,” she says to Jim Parsons’ character, Tommy Boatwright, “all my lesbians friends say ‘What have you guys done for us?’”

This is a spectacular inversion of resentment from the original playtext. Instead of gay men scoffing at the idea of lesbians being included in the movement (“I don’t believe in lesbians”), you have a woman who is only indirectly identified as a lesbian describing her lesbian friends’ disdain for gay men. The disdain is made exponentially worse by the fact of it being reactionary (“What have you guys done for us?”), as if lesbians are inherently heartless misandrists.

Julia Roberts’ character, Dr. Emma Brookner, essentially functions as the supporting stock character on behalf of all women who come to the aid of gay men when even gay men refused to accept the severity of the epidemic. In the HBO adaptation, there is also the mysterious, fictional figure of “Bella Boggs,” who does not appear in the film but whose card is removed from Tommy’s rolodex after she dies, signalling that women, too, are victims of HIV/AIDS.

In some ways the inclusion of Brookner and Boggs (well, at least the rolodex card with “Bella Boggs” typed on it) is the symbolic equivalent of a figure like Mayor Koch — there but not there. Integral but absent, and, more important, absent of their own accord, not because they have been narratively prescripted that way.

The difference is that women have been prescripted that way — women have been erased, and it’s not just evident in the recent adaptation of The Normal Heart. Most recently, this elision came in the portrayal of the HIV-positive trans female character played by a straight white man — Jared Leto — in Dallas Buyers Club, who won an Oscar for that role.

On the level of narrative and of the representation of history, perhaps there is no better example of this erasure of women than that found in the difference between two 2012 documentaries about the crisis: the Oscar-nominated How to Survive a Plague and the lesser known United in Anger: A History of ACT UP. The titles alone illuminate the difference in scope. “How to survive a plague” means working from the inside; white, closeted-gay bond trader Peter Staley becomes the heroic protagonist once he contracts the virus, who is the change agent who works within government and the medical industry. “United in anger” means working from outside that privilege position; it means protesting in the streets, specifically through the organization ACT UP, as opposed to making deals behind closed doors.

It also means, significantly, that we as a people are united in anger, united in protest — working together. United across difference, understanding that HIV does not discriminate.

How to Survive a Plague casts a handful of gay white men as the epidemic’s saviors. As Sarah Schulman, a producer of United in Anger, suggests, How to Survive a Plague misrepresents the extent to which collation activism effected change because it depicts how “five white individuals did it all.”

Schulman, who, with her creative partner Jim Hubbard, established the ACT UP Oral History Project, is not exaggerating. As a lesbian born in 1980, watching films like How to Survive a Plague and The Normal Heart elicit sympathy from me, but not investment. It wasn’t until I watched United in Anger that I understood the extent to which men and women worked together to fight a seemingly invincible villain. Through footage showing how men and women of all races fought the epidemic, the film shows how it wasn’t only about women saving men, but also about men stepping up and fighting for the inclusion of women in the CDC’s definition of HIV/AIDS. “Count the women,” they chanted, “get to work!”

United in Anger, in other words, made me feel invested in all of gay history and showed me how, as a lesbian born at the beginning of the epidemic, how HIV/AIDS is a part of my history.

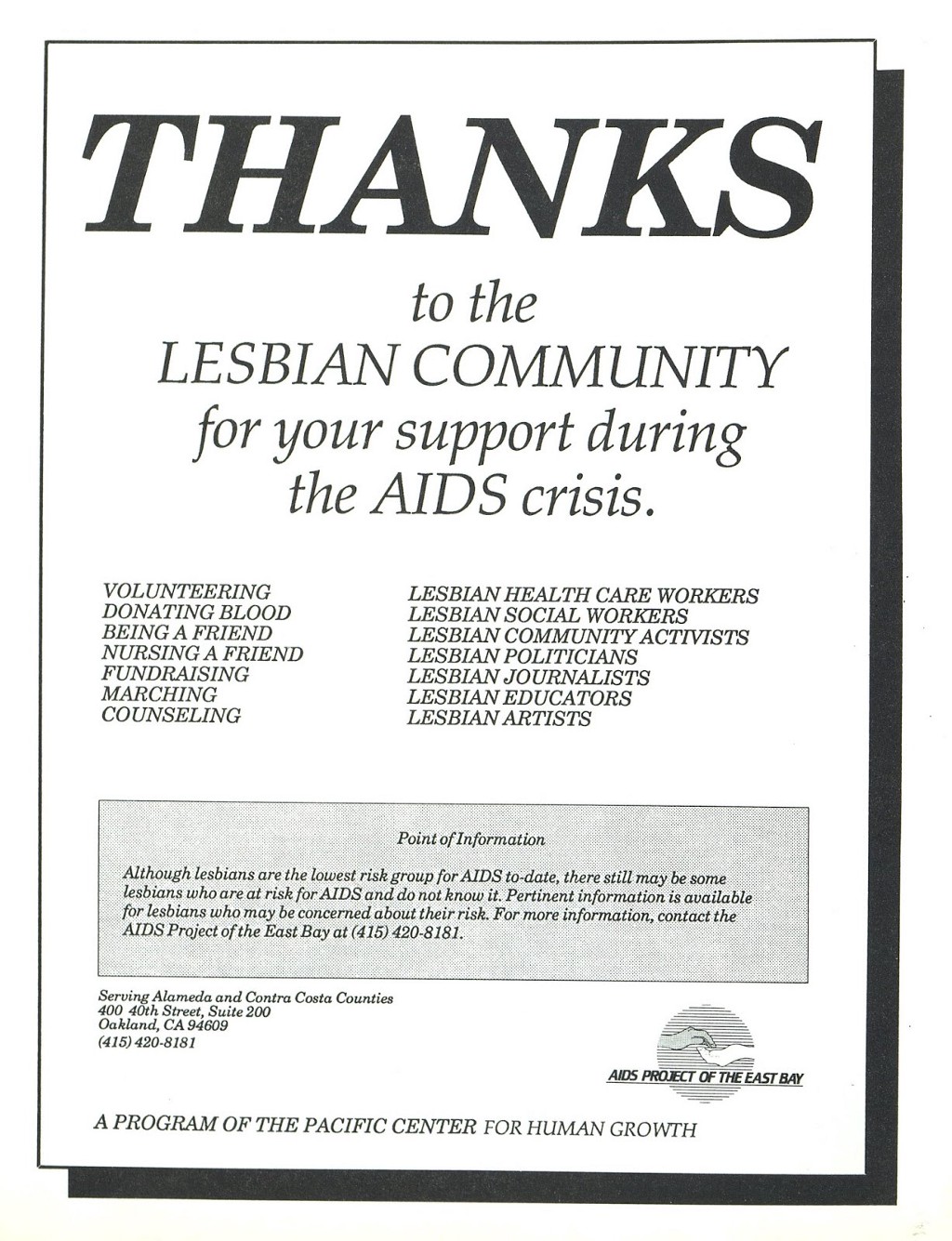

It is interesting to note that it’s only in cinematic portrayals of the crisis that women are overlooked. In protest literature as well as other forms of journalism, women not only have been roundly acknowledged by men but thanked by them as well. In the Winter 1987 issue of the lesbian magazine On Our Backs, the following advertisement was placed by the AIDS Project of the East Bay:

Photo Credit: Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture

The idea of the epidemic as afflicting only the gay white male community, too, seems specific to American culture. Take, for instance, this ad featured on Sydney television in 1987, which clearly states that the virus can infect anyone, young or old, gay or straight, male or female:

Underneath The Normal Heart is the message of universal humanity.

It would serve the film industry well to remember that humanity includes women.