Alma Har’el is a film and music video director, best known for her documentaries “Love True” and “Bombay Beach,” the latter of which was awarded the top prize at the 2011 Tribeca Film Festival. She is also a DGA Award-nominated commercial director. “Honey Boy” is her first narrative feature film, and premiered in the dramatic competition at Sundance 2019, where Har’el won the Special Jury Award for Vision and Craft.

“Honey Boy” premiered at the 2019 Toronto International Film Festival on September 10.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

AH: Shia Labeouf [who also wrote the script] plays his own alcoholic, ex rodeo clown father in a meta-cathartic coming-of-age story inspired by his stormy past as a child actor on the “Even Stevens” TV show.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

AH: “Honey Boy” is my first narrative film. It took 22 days to shoot, and yet it feels like I started working on it seven years ago when Shia LaBeouf first contacted me. After picking up a random DVD at Amoeba Records, and watching my first documentary, “Bombay Beach,” he immediately e-mailed me and asked to meet; at that first dinner he told me about his father, and I told him about mine.

We are both children of alcoholic clowns. While mine was just called that by many because of his humor and approach to life, his was a clown clown. There was no script or any thought of making a movie but there was kinship and understanding only children of alcoholics can share with each other. Years later, when Shia was court ordered to rehab after his arrest, he sent me the script while serving his rehab period.

I’m interested in the process of individuation, and people who have a big heart who can’t find peace. I’m interested in the people who have been left out of the mainstream narrative, and in many ways Shia is the ultimate reject because he refuses to play the game. I think it goes back to how I grew up and how I feel inside society. Shia represents both good and bad things to many people but not many people know what he struggles with.

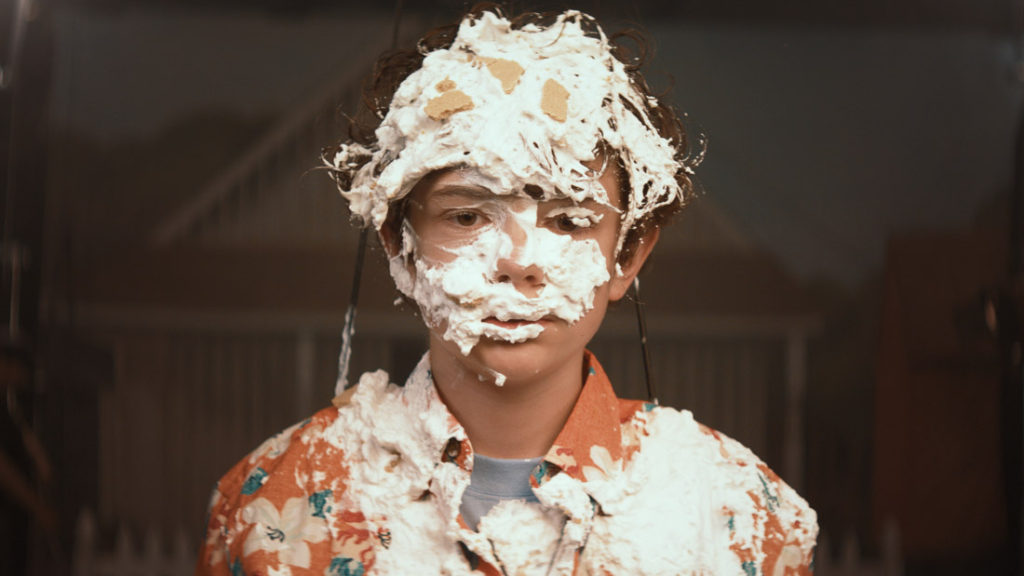

I had an image of Pinocchio in my mind while I was making this film, and I tried to incorporate it: a boy who is hanging and operated by others. He wants to step off the marionette wires and be a real boy, but he keeps lying which causes his nose to get bigger for everyone to see. Pinocchio can become a real boy if he proves himself to be “brave, truthful, and unselfish.” In the end Pinocchio’s willingness to provide for his father and devote himself to be those things transforms him into a real boy.

It reminded me of Shia so much. His lies were never hidden. His acts were always for the world to see and judge. He never had privacy to become a real boy. Knowing him for years, and hearing some of the stories of what happened in his childhood made it possible for me to understand how extraordinary his efforts are to own his destiny, and be the man he wants to be. I was passionate about allowing him to give a performance he subconsciously prepared for his whole life.

W&H: What do you want people to think about when they are leaving the theater?

AH: I made this film for all children of alcoholics because they are all my brothers and sisters.

I don’t want to tell anybody what to feel or take from the film. I myself try to think what all three of my features deal with. I think that there are themes of masculinity and the expectations our fathers have of it, the mythological figures in our lives, the effects of addiction on second-generation, and the thin line between being ourselves and performing ourselves for others.

I love addressing the fact that there are no simple solutions to childhood trauma and daddy issues — the only way out is through. I found in my life that forgiveness and acceptance through creativity is the strongest medicine. This seems to be something that is folded into all of my movies so far, and this movie challenged me to conclude these themes. I think it was an act of exorcism.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

AH: It was all hard. All the time.

Casting the perfect two Otis actors: the young actor when he was 12 years old, and the older Otis when he was 21 and in rehab proved to be extremely difficult, and I feel like I’ve seen every possible actor. I was so lucky that Noah Jupe and Lucas Hedges joined us, and I can’t rave enough about how dedicated and wise they are.

I always laugh that Noah was the most mature person on set. Since this is a movie about a child actor I think he understood it very deeply. Noah has made many successful films, but I think this role will solidify him as one of the strongest actors of the next few decades.

For older Otis, I looked into casting someone that resembled Shia — but I realized after weeks of auditions that it would create a boring movie. Watching Shia play his father, while playing against someone who was similar to him, created no contrast. I was lost during so many auditions and couldn’t find someone that presented the answer to this casting conundrum until I met Lucas.

We met for coffee and within two minutes I knew he was the answer to everything. He had the same search for truth, but he came to it from a very different place, and he had a completely different set of tools to deal with the conflict of feeling like a liar when you act. He also loved Shia, and I could tell that Shia meant something to him. It was important to me that the people who were involved in this were in it for the right reasons.

But the biggest challenge was probably seeing Shia step into his childhood trauma as the man who instigated it, and managing the set around his intense brave act while holding tight to my director’s hat.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

AH: “Honey Boy” was an independent film financed by two incredible women: Daniela Taplin Lundberg of Stay Gold Features (“Beasts of No Nation,” “Harriet”) and Anita Gou of Kindred Spirit (“The Farewell,” “Assassination Nation”). I couldn’t have felt more supported and understood.

W&H: What inspired you to become a filmmaker?

AH: Watching TV at home when I skipped school, and going to see films with my dad when he wasn’t allowed in the house. Crying at films, and understanding things about myself and others. Also dreaming at night. Waking up from long dreams and wanting to dream with other people.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

AH: Best advice: Trust yourself.

Worst: Storyboard everything.

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

AH: Join FreeTheWork.com

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

AH: I can’t name my favorite, but today and many days I love “Ratcatcher” by Lynne Ramsay. It means something to me for obvious reasons.

W&H: What differences have you noticed in the industry since the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements launched?

AH: More reporting of sexual abuse and harassment, safer work spaces, and some cracks in the power structures.