Born in Salvador, Brazil, Liliane Mutti is the founder of the Ciné Nova Bossa Association in Paris. She produces and directs films with strong political engagement, such as “Ecocide,” “Elle,” “Ta Clarice,” “Instant-ci,” and “Out of Breath.” Currently, Mutti is writing a biography titled “Restless/Desatinada,” the behind-the-scenes story of the Bossa Nova movement through the eyes of Miúcha.

“Miúcha, The Voice of Bossa Nova” is screening at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival, which is running from September 8-18. “Miúcha, The Voice of Bossa Nova” is co-directed by Daniel Zarvos.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

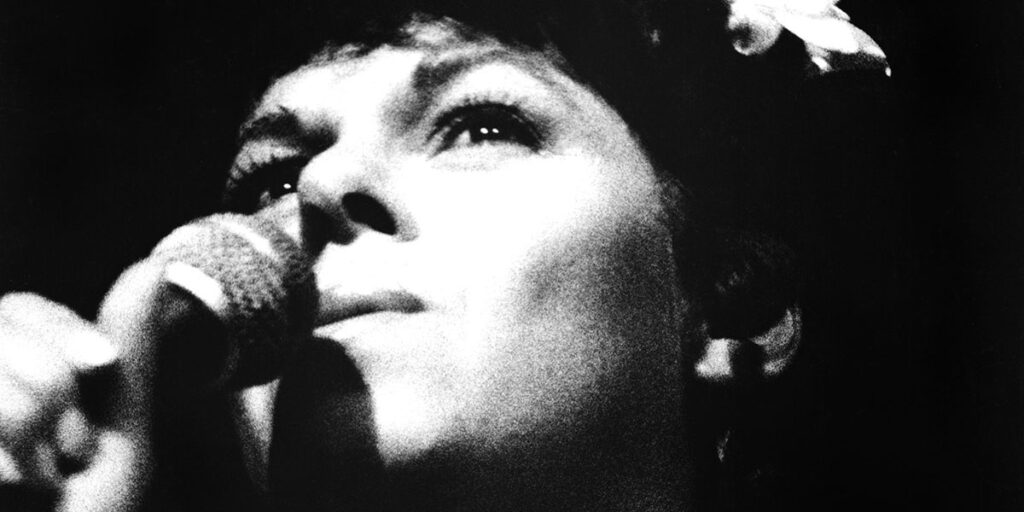

LM: “Miúcha” is a feminist road movie about a woman’s dream of becoming a singer. What could be a simple premise is, in fact, a saga, because everything plays against it: the judgmental look of her mother, the husband who [treats] her as his house secretary, the comings and goings between cities accompanying João Gilberto, the motherhood that is presented to her as loneliness, the financial strains of an unstable career. Whether Miúcha achieves her objective or not will depend on each person’s opinion.

W&H: What attracted you to this story?

LM: The character. Miúcha had unique star quality, and she was someone that when she arrived in a circle, all eyes turned to her. When I met her 12 years ago, I was surprised that there was no film about her.

W&H: What do you want people to think about after they see the film?

LM: To feel the film. I believe that each person will come away with a very particular opinion about the film, the protagonist, and the Bossa Nova movement. I think it’s challenging to leave indifferent because the film touches on some of the most profound myths of the “feminine,” such as the conflict with motherhood, the shadow of the husband, and the expression that behind a great man, there is always a great woman. She didn’t want to be left behind and paid a high price.

All this can be very uncomfortable and have consequences. So if you want to stay on the little blue pill of happiness, don’t watch this movie.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

LM: I think that, like in every biographical film, the most challenging thing is to gain the character’s trust. I always presented myself in front of Miúcha as an assumed feminist. She told me that she was discovering feminism in herself little by little, because we came from very different generations. Miúcha was older than my mother. When we started shooting the film, she and João Gilberto called [co-director] Daniel Zarvos and me “the kids.” Ten years later, from the time of the script to the film’s release, we are no longer the same young ones [laughs].

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

LM: The first investment that the film had was from Rio Filme, a distributor in Rio de Janeiro, from Marco Aurelio Marcondes, who is a great admirer of Miúcha and a great visionary of Brazilian cinema. He was removed from the presidency of the agency when fundamentalist evangelicals came to the city hall, and all the talk about financing for cinema in Brazil became complicated. The film “Miúcha” behind has a free look at the nonconformity of the sexual revolution and the liberation of marijuana in the United States. Imagine all this in the misogynist misgovernment of [Brazil’s president Jair] Bolsonaro.

So Daniel Zarvos, who did his film studies at Bard College and had a great network of contacts in New York, found a producer with a passion for Brazilian music and sensitivity for this feminist story we wanted to tell. He joined Filmz, a French-Brazilian-American producer, and with producer Marta Sanchez, we set up a power team with 50 percent women and 50 percent men, which is the reasonable minimum to change an unequal industry in terms of gender and race.

W&H: What inspired you to become a filmmaker?

LM: I come from TV, where I worked with series and musicals for 20 years. Cinema has always been a distant dream because, when I went to college in the ’90s, this was not an option in Bahia, the state in the northeast of Brazil where I come from. I am from a generation born in the ’70s, so I had a childhood still in Brazil, suffering a military dictatorship that lasted 21 years. But when I had a daughter, I felt great urgency to tell stories and put a narrative through women’s eyes and bodies.

At the same time, in August 2016, the first woman president of Brazil, Dilma Rousseff, suffered a media-legal-parliamentary coup d’état, and there I felt something overflowing. So I went back to university, Paris 8, to research gender issues in Paris and started to make one short film after another. Still, I kept obsessing over the character of Miúcha. There was no turning back. I saw that I had become a filmmaker, and at that moment, I launched “Miúcha” with Daniel Zarvos, and at the same time, I finished the first feature film that I signed on my own, “Hello, My Friends!” and started shooting my first fiction feature film.

Cinema is a real pain in the cachaça, like an addiction.

W&H: What is the best and the worst advice you have received?

LM: It was from Tereza Trautman (“Os Homens Que Eu Tive”/”The Men I’ve Had”), a Brazilian filmmaker from the Cinema Novo generation. She called me to a meeting at the channel she directs, CineBrasilTV, and said, “Keep showing your village!” At the time, I was doing my second travel series, which aired on several channels in Brazil. There, I decided to make a new season of this series (“Decola”) and went to the Amazon in partnership with Daniel Zarvos.

This was a watershed moment for us. He decided that his second film would be “Maíra,” an adaptation of Darcy Ribeiro’s novel, and I decided to move to Paris. I needed to see Brazil from the outside to be able to breathe in times of the extreme right. From this re-encounter with Brazil, I saw myself more as a woman, Latin American, immigrant, and self-exiled each day.

W&H: What advice do you have for other women directors?

LM: Art is an invention. The most important thing is that you believe in what you do. If you don’t believe in it enough, no one will. So, no matter how much they tell you, it doesn’t make sense. What makes sense is what you put into your work intensely. In my case, I put my womb, my sex, and my anger.

W&H: Please name your favorite film directed by women and why.

LM: If I have to choose only one, I’ll stick with “Salut les Cubains” (1963), by Agnès Varda. In this film, assembled only from photos and black and white, she re-creates the movement of dance and puts a personal look on this foreigner’s place. She created a hybrid cinema between plastic arts and photography. She was already revolutionary at the time of the nouvelle vague and went on until the end of her life breaking patterns.

Of the new generation, I really like Maria de Medeiros as an actress and filmmaker.

W&H: What responsibilities, if any, do you think storytellers have to face the turmoil in the world, from the pandemic to the loss of abortion rights and systemic violence?

LM: Here in France, I militated in the I Did Movement, where women, especially Brazilians abroad, told their experiences, including myself. Abortion in Brazil is criminalized, and this is so wrong. I think this debate between political and non-political cinema is a false debate. I am with Costa-Gavras: all cinema is political. “Miúcha” is a political film, and I also say this as a screenwriter. I read practically all the letters and diaries written by her between the ’60s and ’70s, the period she was married to João Gilberto, and I can confirm that João Gilberto would not exist without Miúcha. The record “The Best of Two Worlds,” which Miúcha and João Gilberto made with Stan Getz, wouldn’t exist, nor would João’s famous white album.

W&H: The film industry has a long history of underrepresenting people of color on screen and behind the scenes and reinforcing — and creating — negative stereotypes. What actions do you think should be taken to make Hollywood and/or the doc world more inclusive?

LM: I am an active activist for quotas. I believe that social redress is only possible with practical measures, such as putting down the cameras when stereotypes are bandied about. Right now, I just got a backup funding line in São Paulo for an animation aimed at the pre-teen public. How do I feel? I’m doing my part. If filmmakers can do it, the industry can do even more.