Mami Sunada was born in Tokyo

and studied documentary filmmaking at Keio University. She broke into film by assisting director Hirokazu Kore-eda on Still

Walking and Air Doll. She also wrote and directed Death of a Japanese Salaryman. (TIFF official site)

Her latest film, The

Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, played at TIFF.

WaH: Please give us your description of the

film playing.

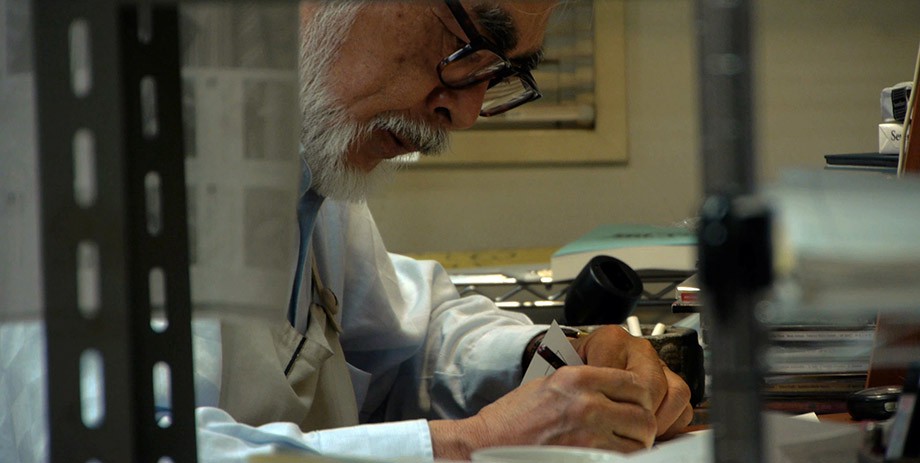

MS: Studio Ghibli, a nationally

recognized studio in Japan, was in a state where two films, The Wind Rises and The Tale of Princess Kaguya, were being directed by Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata during the same year. This was very unusual, and thus a memorable

event that both were in production at the same time. Since I was granted

such rare access for this documentary in such a busy year, I was able to

capture many of the details of the studio’s production process.

WaH: What drew you to this story?

MS: This project started off as

a request from Disney Japan to make a commercial DVD, but as soon as I started

going to Studio Ghibli, I realized that in order to depict the studio in a

comprehensive manner, it should be done as a feature film instead. I had

the intuition that this would be a historic year for Studio Ghibli, so I

thought, rather than just having a video to promote it, I wanted to give a more

in-depth glimpse at the daily operations within the legendary studio.

WaH: What was the biggest challenge in

making the film?

MS: There were three major

obstacles for me to overcome before I could get the access I needed to Studio

Ghibli. The first was producer Mr. Suzuki, who initially was reluctant to

agree to the approaches I suggested. It was only when I said I wanted to

make this into a documentary feature film that he gave me his support, and only

with the condition that I approach directors Miyazaki and Takahata myself.

Mr. Miyazaki was right in the middle of production for The Wind Rises, so it was hard to find

the time to start really filming him. I went daily to see how he worked

and to figure out how best to approach him. Mr. Takahata was even more

difficult. If Miyazaki was Mount Fuji, then Mr. Takahata was Mount

Everest. With the release date for the documentary looming, I had no

choice but to overcome these difficulties on a tight deadline.

WaH: What do you want people to think about

when they are leaving the theatre?

MS: Regardless of the audience’s

interest in animation, I would hope that they leave the theatre with an

appreciation for the value of consistent, hard work. These three

animation filmmakers show how difficult it is to actually finish these

projects, and how the result of repeating quality work every day can be

something really incredible.

WaH: What advice do you have for other female

directors?

MS: Actually, I would like get

advice from other female directors! It’s still early in my career, but so

far what I have learned is that female filmmakers need to really focus on

patiently and persistently explaining their vision to producers.

WaH: How did you get your film funded?

MS: At first, we had no

production funding set up at all, so both Mr. Suzuki and Mr. Miyazaki at Studio

Ghibli were concerned about how I was funding myself and the project. They helped set me up with Mr. Nobuo Kawakami, who is the head of

Dwango Co. and was a producer on this film, and he ultimately ended up funding

the film via Dwango.

WaH: Name your favorite woman-directed film

and why.

MS: Open Hearts directed by Susanne Bier in 2002. It’s a fully realized work of

entertainment, but it also shows what it means to be human. It very

delicately shows the loneliest parts of life, as well as the inner and outer

aspects of people.