Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy is an Academy-and Emmy Award-winning documentary filmmaker. Her work centers on human rights and women’s issues. She has worked with refugees and marginalized communities from Saudi Arabia to Syria and from Timor Leste to the Philippines. (Sharmeen Obaid Films)

“Song of Lahore” will premiere at the 2015 Tribeca Film Festival on April 18.

W&H: Please give us your description of the film playing.

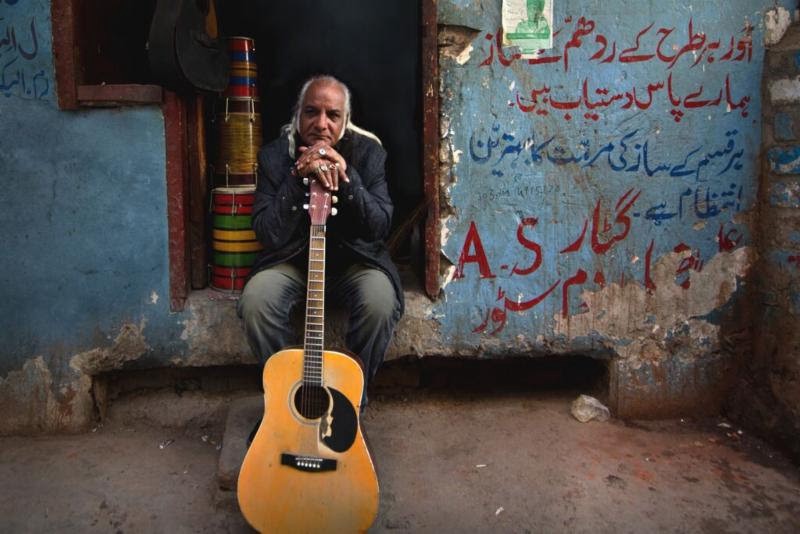

SOC: The film follows the story of Sachal Studios, a group of classically trained musicians who used to work in the Pakistani film industry. When the film and music industries declined in the wake of increasingly conservative Muslim laws and social customs in Pakistan, many of these musicians found themselves out of work. They were brought together at Sachal Studios by Izzat Majeed, who built the studio in order to preserve these musical traditions.

After releasing a number of South Asian classical and folk albums with little fanfare, they released an album covering Western jazz standards with their traditional instruments, such as the sitar, flute and tablas. It became a surprise hit, as the video for their arrangement of Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five” went viral. The media coverage that followed led to their invitation to perform with Wynton Marsalis at Jazz at Lincoln Center.

Despite their rising international acclaim, Sachal Studios remains virtually unknown in Pakistan. The ensemble is faced with a daunting task: to reclaim and reinvigorate an art that has lost its space in Pakistan’s narrowing cultural sphere. The film asks an important question: Is there still room for musicians in a society embroiled in social, political, and religious upheaval?

W&H: What drew you to this story?

SOC: I grew up listening to my grandfather’s stories of our musical past. He would often talk about the orchestras that played at concerts and the musicians who played on Sunday evenings on street corners. By the time I grew up in the ’80s, all of this was a thing of the past. I lived vicariously through his stories and often wondered what it would have felt like to have been part of his generation.

In 2012, I came across the story of a group of musicians from Lahore who had come together against all odds to record music using Pakistan’s traditional instruments, and I knew that was a story I wanted to tell. At that time, I had no idea what the group’s journey would be; I just wanted to preserve their voices and their music. And what a journey it turned out to be.

From Lahore to Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York, these musicians found their inner calling. As our cameras filmed them performing a sold-out concert with Wynton Marsalis, I thought back to my grandfather’s stories of our past and knew that I had managed to experience some of those moments that night.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

SOC: There were a lot of unique challenges in producing the film, such as the logistical issues inherent in producing a long-term verite film in Pakistan, dealing with Urdu and Punjabi dialogue with an English-speaking editor and all the difficulties in recording, editing and clearing so many music tracks. But the biggest challenge overall was narrowing down the complex narrative elements into a clean and straightforward story while maintaining a sense of the cultural context that makes the film special.

W&H: What do you want people to think about when they are leaving the theater?

SOC: I want people to leave the theater with a greater understanding of the rich cultural heritage of Pakistan. “Song of Lahore” moves beyond headlines and stereotypes and shows that a vast majority of Pakistanis are not perpetrators of religious violence — they are victims of it. The beautiful cultural heritage of the region belies its image in the West as monolithically religious, intolerant, and violent.

By giving our audience intimate access to the lives of these musicians, we hope to raise awareness of the region’s beautiful cultural heritage and present a more nuanced portrait of its people. As one of the film subjects, Nijat Ali, says in the film, “God willing, the entire world will see that Pakistanis are artists, not terrorists.”

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

SOC: My advice to other female directors would be to pay no heed to naysayers. Women can be united in the fact that there has always been someone in our lives who has told us “it can’t be done” or “there is only so much you can do.” We are constantly encouraged to think that being born a woman means we were born with limited choices and compromised dreams.

I became a documentary filmmaker because I wanted to make socially conscious films. I never studied filmmaking — everything I have learned has been on the field. For my first film, I wrote about 80 film proposals, mailed them out and waited. I received so many rejections that I lost count. But with each “no,” I knew there would be a “yes” somewhere — there had to be a door that I had not yet knocked upon. And there was. One day, an email I wrote came back with a positive response. Ten years later, I was making an acceptance speech at the Oscars, and all I kept thinking was thank god I kept knocking!

W&H: What’s the biggest misconception about you and your work?

SOC: It’s often said that I choose subjects that are sensational! My answer is that I choose to film subjects that spark difficult conversations and make people uncomfortable. Change only comes about when people are forced to discuss an issue, and that’s what I hope my films do.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

SOC: We raised our funds from private donors, family foundations and investors.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

SOC: My favorite woman-directed film is “Monsoon Wedding” by Mira Nair. It is a beautiful story of several generations set in India. I absolutely love the way Mira has told this story of families trying to hold their ground against change. The wedding, which is at the heart of the story, provides humor but also unveils deep-seated issues that open up a window into a society at war with its culture.