Sierra Pettengill is a Brooklyn-based filmmaker. “Town Hall,” her directorial debut (co-directed by Jamila Wignot), broadcast nationally on PBS in 2014. She produced the Academy Award-nominated documentary “Cutie and the Boxer.” Pettengill was also the archivist on numerous films, including “Kate Plays Christine” and “20th Century Women.”

“The Reagan Show” will premiere at the 2017 Tribeca Film Festival on April 22. The film is co-directed by Pacho Velez.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

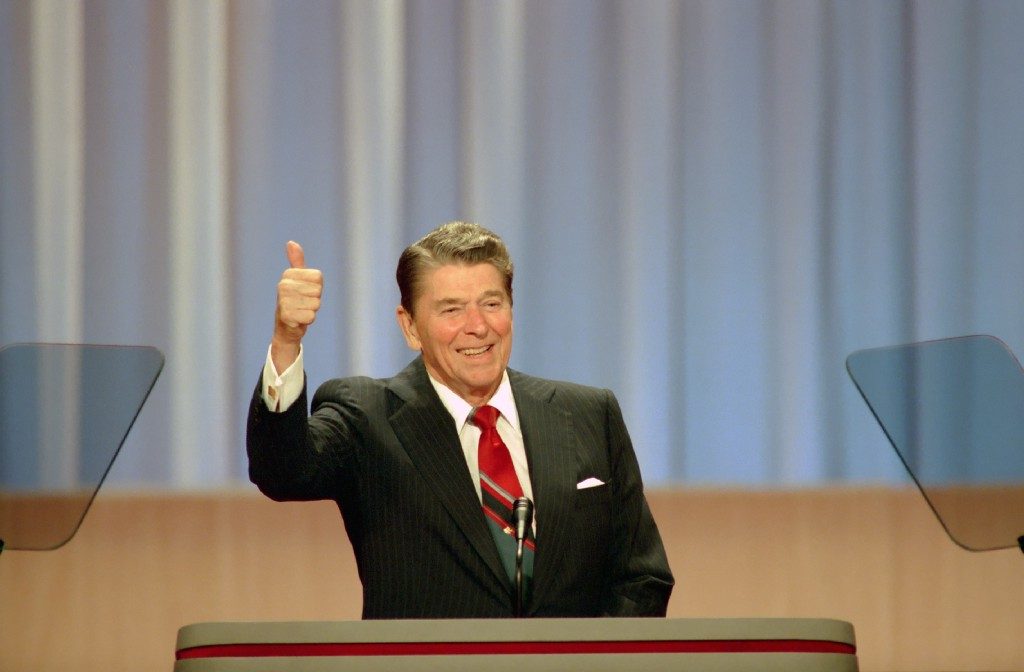

SP: “The Reagan Show” is an all-archival documentary that presents the pageantry, absurdity, and charisma of a prolific actor’s defining role: Leader of the Free World. Told solely through 1980s network news and videotapes created by the Reagan administration itself, the film explores Reagan’s made-for-TV approach to politics as he faced down the United States’ greatest rival. Lots of analog video and prescient political drama.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

SP: I am really fascinated by the stories that America tells itself about who it is and the ways that those stories are propagated, reinforced, and repeated. With this film, it was pretty thrilling to go back several decades to a decisive historical moment where you can really see some of the roots of the present day starting to take hold.

As an archival researcher and archival producer, I work a lot with archival footage, and I always want to consider historical materials within the context under which they were produced. That was really exciting prospect for me here; rather than applying the tapes to a pre-determined story or cherry-picking it for illustrative purposes, we sat in both the network news and the Reagan-authored WHTV tapes, and reckoned with it as a body of footage that was shot for specific purposes and told from very specific perspectives.

W&H: What do you want people to think about when they are leaving the theater?

SP: Looking at Reagan through the prism of performance feels like the best way to understand both the person and the policies he pursued, as well as the role of “narrative” itself.

We want this self-reflective approach to invite viewers to look closely at — and question — the tools employed in politics and the ways that we, as the citizen-audience, receive information.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

SP: Grappling with the breadth and quantity of footage — which clocked in at around 1,000 hours — and the near-limitless permutations allowed for within the shaping of the edit.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

SP: The film was funded through a mix of grants, a pre-sale to CNN Documentary Films, and investment from Impact Partners.

W&H: What does it mean for you to have your film play at Tribeca?

SP: It’s always really special to show your film in your hometown! There were so many incredibly talented people who made this film, and most of them live here in New York, so I’m really grateful that we’ll be premiering it here.

Also, the programming this year feels especially strong, which is a real honor to be part of.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

SP: Oh, I don’t know. It’s a constant triangulated process of checking in with those who care the most about about you, those whose work you admire, and your own angst, isn’t it?

I guess “work harder” is persistently both my best and perhaps also worst advice to myself.

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

SP: That therapists will often negotiate reduced rates for artists.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

SP: Chantal Akerman’s “Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels” is likely to reside permanently at the top because it first changed what I thought movies could do or even be.

Among other things, it taught me how to do a certain kind of looking, how to use stillness to draw attention to what you want to be seen, and how politically and emotionally charged a lack or absence can be.

But, a few months ago, I at last watched her incredible final film “No Home Movie.” I’ve found that I’ve been carrying around the two films, wrestling with each other across the decades from a pair of living rooms and kitchens, intertwined in my head ever since.

W&H: There have been significant conversations over the last couple of years about increasing the amount of opportunities for women directors yet the numbers have not increased. Are you optimistic about the possibilities for change? Share any thoughts you might have.

SP: This is — obviously — such a complex issue, and I have to admit that I get really stuck on the metrics often used to frame the conversation. In this case, limiting the discussion solely to the numbers around “women directors” really eliminates some of the more fundamental issues that I see as being in play regarding how women operate in the arts — namely, how female labor is valued and appreciated.

I mainly work in documentary, so I can only speak to that. But, if you glance just one row down below the director credit, you’ll often see that the majority of the positions down the line, starting with the producers, tend to be held by women.

I think it’s really important to question why the same roles that are more typically filled by women are also those that tend to be devalued in comparison to the director. It’s related to a broader, more general problem in understanding and highlighting the labor that goes into filmmaking.

So, the question shouldn’t just be, “Why aren’t there more female directors?” (which I agree is important); it should also be, ‘“Why don’t we equally recognize the labor that women are doing as the backbone of production?”

Recently, filmmakers like Anna Rose Holmer and Kirsten Johnson have gone out of their way to insist on the primacy of their crucial collaborative partnerships, which I think is both inspiring and just plain correct.