Susanna White is a BAFTA award winning director who began her career making documentaries such as “Tell Me the Truth About Love.” She made her feature narrative debut with “Nanny McPhee Returns,” which was followed by “Our Kind of Traitor.” She has also directed the critically acclaimed television series “Bleak House,” “Jane Eyre,” “Generation Kill,” and “Parade’s End.”

“Woman Walks Ahead” will premiere at the 2018 Tribeca Film Festival on April 25.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

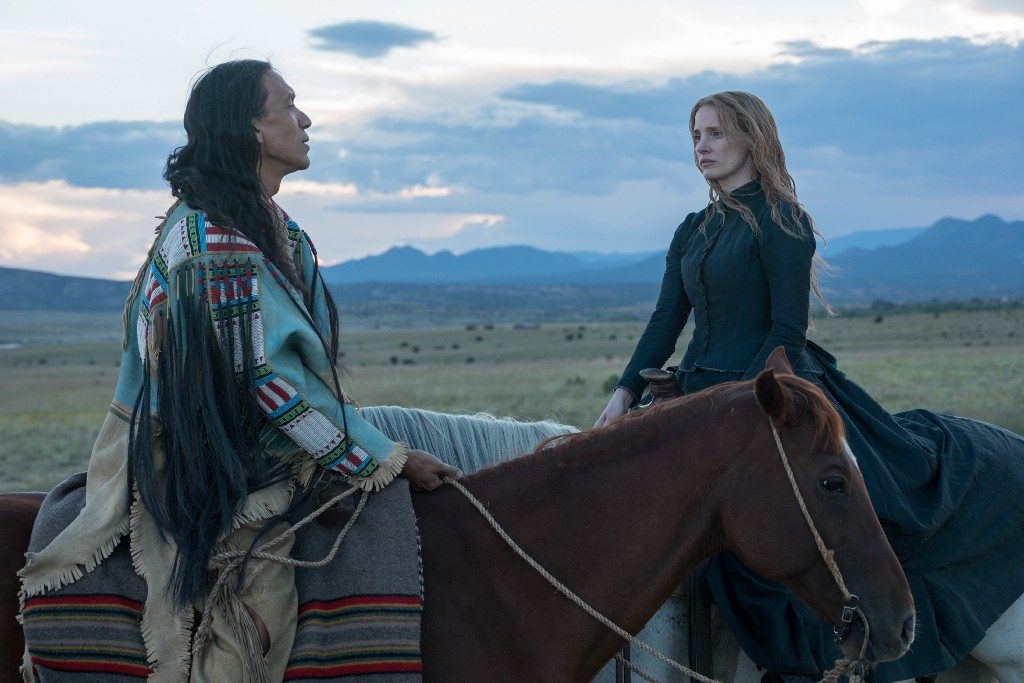

SW: “Woman Walks Ahead” tells the story of Catherine Weldon (Jessica Chastain), a portrait painter from New York, who, in 1890 set out on her own from New York to the Dakotas to paint a portrait of Sitting Bull (Michael Greyeyes).

Mistakenly thinking she would find freedom in the lifestyle of the Sioux Indians in contrast to the oppression women faced in New York, Weldon becomes increasingly politicized as she discovers that Sitting Bull’s people are in danger of losing their ancestral lands.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

SW: My agent gave it to me because I was looking for an epic love story — something in the tradition of films like “The English Patient,” by Anthony Minghella. In fact, this isn’t a love story in a conventional sense at all — it is the story of two oppressed people giving each other hope. As soon as I read it I knew I had to make the film. It spoke to me so strongly.

I grew up loving the epic landscape of Westerns. This is set in that world but you hear the stories of people you don’t normally hear in those narratives — the Native American community, and a strong woman. There’s also a very spiritual aspect to the movie that drew me — the sense that the land was there before any of us, and will be there after we have passed through it.

I had always been interested in Native American history. My father worked at the Hudson’s Bay Company in London, and in the reception there was a glass case with a full-size figure of a warrior dressed in an eagle headdress and a war shirt. I was always drawn to it, and spent ages looking at the feathers and beadwork.

After I left film school I went to watch a ceremony on the Hopi reservation, and was fascinated by the sense of how ancient and spiritual the culture was in contrast to the modern America I knew in Los Angeles.

W&H: What do you want people to think about when they are leaving the theater?

SW: I’d like people to reflect on their history. I was very moved when our Lakota language adviser, Ben Blackbear, watched the movie, and said he hoped it would change the way history was taught in schools because it was telling a story his community usually didn’t get told. What struck me, doing the research on the Lakota people, and reading about Sitting Bull, was the sophistication of the culture.

The quality of the artwork and textiles is extraordinary, and Sitting Bull was a man of such wisdom — there are so many great quotes from him, my favorite being, “The greatest strength is in gentleness.” That is such an antithesis to the conventional narrative of a Western.

I’d like people to reflect on the value the Sioux people put on co-existing with the natural world — taking only what they needed so they didn’t exhaust natural resources. There are lessons for the modern world to draw from that.

W&H: What were the biggest challenges in making the film?

SW: In making this movie I was very conscious of being, like Weldon, an outsider. While I could relate to being a woman in late 19th century New York, I knew I had a huge amount to learn about Native American culture. I asked for help from the community, and had an amazing experience when I was invited to stay on the Rosebud reservation to watch a Sun Dance ceremony.

People were incredibly generous in coming forward to teach me, and share their traditions. Many of these were deeply spiritual — for example, the Ghost Dance that we show in the film was a sacred dance which hadn’t been performed on the scale we were doing it in the movie for over a hundred years. I felt a great sense of responsibility to get that right. We also had wonderful crew members from the community as well as cast who would offer up help on the day.

This was not a big budget movie — we shot it in 31 days. I had to be very focused every day on what were the most essential elements of every scene in order to make the days. I made a decision to jettison big set pieces, and focus on the emotional heart of the film.

Mike Eley, the cinematographer, and I also worked to give the movie scale by offering up big skies and landscapes — at the heart of the film is the story of our relationship to the land, and its scale came from the wonder of the natural world rather than big builds or crowd scenes.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

SW: Period dramas are always challenging for independent film — this was a very ambitious movie, taking someone from New York to the plains of Dakota in the 1890s. There were a lot of reasons why it had taken 14 years to get made. It has not always been easy to finance a movie with a female lead, and there have been very few Native American actors with big box office profile.

Fortunately times are changing, and with Chastain attached we managed to attract finance from Erika Olde at Black Bicycle Entertainment, who has been very committed to strong female stories. Sales estimates didn’t match the original needs of the budget so I cut some of the big set pieces — Brooklyn Bridge, New York Street scenes, and a big steamboat sequence — in order to concentrate on what I felt was the emotional heart of the story.

We played to our strengths, abandoning crowd scenes for big skies, and landscapes in which people are dwarfed by nature.

W&H: What does it mean for you to have your film play at The Tribeca Film Festival?

SW: It’s so exciting to have “Woman Walks Ahead” play at Tribeca, especially in a year in which 46 percent of the films at the festival are directed by women. It’s especially appropriate to have the movie play in New York, as Catherine Weldon started out on her journey from Brooklyn, and returned to settle there, eventually dying in a house fire.

W&H: What is the best advice you have received?

SW: The best advice I have received is from the British producer, Tony Garnett. I worked with him early on, and he told me that you never want to see any acting going on. That has always been my touchstone.

If you feel the mechanics of the acting something isn’t right, and it is my job as the director to shift things in order to free up the actors to give their best.

W&H: What advice do you have for other female directors?

SW: I have never really seen myself as a female director, just as a director who happens to be a woman — but I know that is not how the world always sees us. I’d advise other women to try to bounce back when they get knocks, and not to give up. If you want it enough you will get there in the end.

The most important thing is to listen to your own voice — that can be hard sometimes when there aren’t many female voices being heard out there.

W&H: Name your favourite woman-directed film and why.

SW: It has always been Jane Campion’s “The Piano.” Almost every time I embark on a new piece of work I watch it — it is such an inspiration. Up until I saw that movie I knew I wanted to be a filmmaker, and admired huge numbers of films, but there were not that many films I could connect to on a really deep level.

When I saw “The Piano” it was like someone was singing in a key that felt like me whereas the other films had been in a different range. It’s not that I want to re-make “The Piano.” It is just that it has such a clearly female voice that is so different from what went before.

W&H: Hollywood and the global film industry are in the midst of undergoing a major transformation. Many women — and some men — in the industry are speaking publicly about their experiences being assaulted and harassed. What are your thoughts on the #TimesUp movement and the push for equality in the film business?

SW: It feels as if we are in a real moment of sea change for women in the industry. There has been a huge snowball effect with people at all levels right across the industry standing together not only against bullying and harassment but also campaigning in terms of equal pay.

There are still lots of broader areas to work on, like the shortage of female film critics which affects how films are received, and diversity behind the camera, but I feel a really widespread desire for change that has come about as a result of people uniting around the world. The power of the internet has been huge in enabling this to happen.