House of Cards, Netflix’s buzzy political drama, started life as a remake of a British miniseries. Starring Kevin Spacey as Frank Underwood, an amoral, ambitious member of Congress, it also felt derivative of the many other dramas focused on male anti-heroes that have come before it, relying heavily on surprising acts of violence, a license to be explicit about sex, and a cynicism about human nature that insists we find it deep. But in one respect, it offers us at least a little bit of innovation. Claire Underwood (Robin Wright), Frank’s amoral wife, isn’t the first attempt to create a female anti-hero, and she has much in common with many of the TV women who came before her, but she does push the trope further, testing just how far a female character can venture from what’s expected of women before she becomes utterly unsympathetic.

Damages, which aired both on FX and DirecTV, gave us Patty Hewes (Glenn Close), a brilliant but deeply cynical lawyer whose willingness to champion progressive causes gave her an excuse to behave ruthlessly. Claire first worked on cleaning up DC’s watershed, then dropped her local efforts for a trendier venture in international aid before pursuing reforms in the way the military handles sexual assault cases, in part as a way to pursue a personal crusade for justice against the general who raped her. In a similar way, it wasn’t always clear how committed Patty actually was to her causes, which ranged from a class-action suit against an Enron-like CEO to a case against a military contractor, or if she simply enjoyed the status and moral authority — and the license to pursue her enemies relentlessly — those cases conferred upon her.

And in a classic way of painting women as unlikable, Claire and Patty share a distinctly alienated approach to parenthood. Claire’s advocacy against sexual assault is in part an effort to distract the media from covering her confession that she had an abortion. In reality, she’s had three — one during a campaign because she and her husband believed that pregnancy and childrearing would get in the way of their rise to power (or, as Claire puts it to the press, to public service).

Patty has a child, a son named Michael, but she’s a singularly horrendous mother with essentially no relationship to him, and he learns from her manipulations. At one point, Patty tries to pay his older girlfriend to break up with him, eventually having her arrested on statutory rape charges. Michael retaliates by hitting her with his car. In the final season, a hitman Patty hired ended up killing Michael instead of his intended target. It’s about as close as a human character can come to eating her young without resorting to cannibalism.

But if Patty did more damage over five seasons of Damages than Claire has done in two of House of Cards, it’s still, in some ways, easier to admire Patty than it is to like Claire. Patty, like some of the best male anti-heroes, was often truly competent. She did dreadful things, but her skills in a courtroom and in the thousand battles on the way to any trial were formidable, and they could produce genuinely good outcomes for her clients.

Claire, by contrast, is a dilettante. She skips out on one cause when she decides it’s not sexy enough, blows up her non-profit organization in part to get revenge on a former employee, and abandons military reform when the going gets tough, though not before she’s helped ruin the life of a vulnerable young survivor. Claire is a creature of the political news cycle, moving from one advantageous position to the next without much concern for whether or not she’s achieved anything of substance. And unlike Patty, who has an independent career, Claire is in a profound way an old-fashioned wife, a woman who’s built her life around a man and his ambitions. There’s a meanness to her in the most traditional sense, a lack of the tactical or strategic grandeur that inspires admiration for even the most repulsive anti-heroes.

Next to her more hot-blooded female anti-hero counterparts, Claire’s a positive reptile. On FX’s motorcycle gang drama Sons of Anarchy, Gemma Teller Morrow (Katey Sagal) may share Claire’s self-centeredness and manipulative nature. But she does so from far more interesting circumstances. Teller Morrow was married first to John Teller (Nicholas Guest), the founder of the Sons of Anarchy gang, and then to Clay Morrow (Ron Perlman), his best friend, who brought about Teller’s death to supplant him in leadership of the gang and in Gemma’s life. These circumstances mean that Gemma is a more formal analogue to Lady Macbeth than Claire, who approximates their common literary forebear only in her position behind the throne.

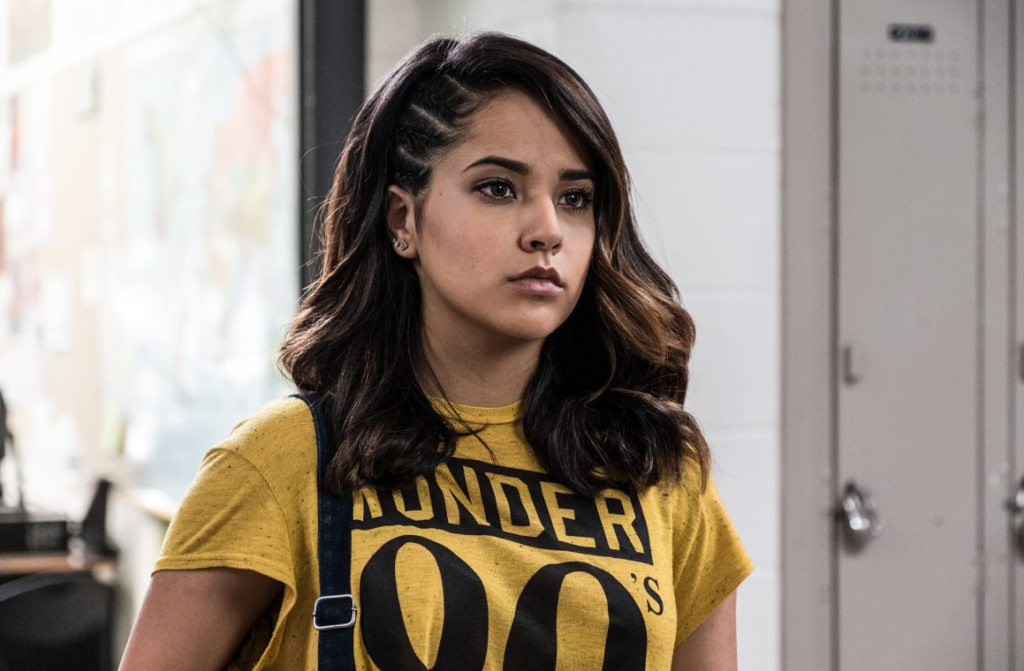

Gemma is hardly morally pure, but she’s often a more sympathetic character than Claire is. While Claire comes from a place of extreme economic privilege — House of Cards’ second season strongly implies that Frank married her so she could help finance his campaigns — Gemma is working class. Claire’s decision to be a professional political wife in an environment where women like Congresswoman Jackie Sharp (Molly Parker) can attain great power marks her as a sort of deliberate throwback. But for Gemma, attaching herself to a powerful man is one of the few options she has to rise in the world — to attain the trappings, if not the manners, of middle-class life.

Gemma does things that are far uglier than any of Claire’s sins, including murdering her own daughter-in-law. But she’s in many ways a more complete and compromised personality than Claire, who’s erased much of what made her unique so she’d fit more smoothly into her role as a wife. We can see Gemma’s needs and even sometimes her desperation, while Claire seems to move from want to want.

Next to Claire’s cold caprice, Elizabeth Jennings (Keri Russell), the deep-cover Soviet spy on FX’s The Americans, seems almost cuddly. Unlike Claire, who chose marriage for her own purposes, Elizabeth allowed the KGB to set her up with her now-husband Phillip (Matthew Rhys) as part of her disguise in the Washington suburbs. She understands her marriage, however unusual its origins, as a far purer form of service to her country than Claire does. Elizabeth has a body count that makes the psychological ruin Claire leaves in her wake looks paltry. But as a spy, Elizabeth is playing a game that everyone involved knows has a high casualty rate. Claire, by contrast, ruins people who thought they were safe with her, be they a former lover or a young woman she’s pushed to speak publicly about her sexual assault.

And ultimately, while we may disagree with Elizabeth politically — few of us would have shared her dreams of Soviet victory — or be horrified by her line of work, which includes honeytrapping and assassination, The Americans is also the story of her coming alive as a wife and mother. In the first season of the show, Elizabeth struggled with the fact that for Phillip, their marriage was real, while she had not quite fallen in love with him; the second year of The Americans begins with them on the same page. And while her children may be a convenient part of her cover, Elizabeth loves them deeply, aborting her recovery from a gunshot wound early to be home for her son’s birthday. Claire Underwood may be a Democrat, but even if we agree with her nominal politics, her decidedly chilly attitude towards family and her indifferent approach to her work might make Elizabeth a preferable dinner date.

Since the runaway success of The Sopranos, it’s been common to plumb the experiences of male anti-heroes for lessons about American masculinity, a practice that continues to this day with HBO’s anthology series True Detective. But what do Claire Underwood and all the difficult women before her tell us about the state of American women?

We can admire Patty Hewes, despite her repulsive attitudes towards her son, in a twisted sort of way, because there’s at least something understandable about how awful she is as a mother. She represents a generation of American women who seem to have felt that they needed to at least gesture towards motherhood to make people comfortable with their professional ambitions, rather than pursuing them without constraint or shame. Patty lives in a prison of her own making, and comes to sorrow by her own hand.

Gemma Teller Morrow does dreadful things because she over invested herself in a particular vision of her family’s safety and prosperity. Without a career, and without both of her husbands, Gemma’s become obsessed with her grandchildren. She’s the reverse sort of cautionary tale.

And Elizabeth Jennings exists in a space in between them. She’s very good at a job that requires her to do very bad things, which means we can admire her as a talented professional, even if we’re appalled by her goals. And she’s trying to figure out how to be a good wife and mother, a particularly difficult task given the way her family life started, and the extraordinary secrets she’s keeping from her children. In Elizabeth, we have a period vision of a strikingly modern dilemma. How do women who want both work and family balance both? And how do women to whom marriage and motherhood don’t come as naturally as they’re supposed to learn from those things?

While all these women struggle with the dilemmas of modern womanhood in ways that have sympathetic roots, Claire Underwood seems like the worst of both the old ways and the new. Her primary identity is as a wife, and she’s lazy and disinterested in her work in a way that does great damage to other people, from the secretary she lays off in the first season to the potential beneficiaries of her charitable efforts, who see them withdrawn at Claire’s whims. But Claire is also a monstrous caricature of what feminism hath wrought, a woman who aborts her pregnancies to pursue her ambition — and whose relationship with her husband is the sort of power-oriented arrangement that’s more poisonous than any dreamed up by Clinton conspiracy theorists.

Anti-heroes have often served as a reminder of just how highly we value masculinity even when it’s turned towards toxic ends, whether it’s Tony Soprano lording it over his family, or Breaking Bad’s Walter White becoming a master criminal in his efforts to prove his own genius. But characters like Claire Underwood are a reminder that femininity is a trickier proposition. Whether she’s choosing the security of wifehood or the independence of childlessness, Claire Underwood and her fellow anti-heroines are a reminder of the extent to which female characters still have to justify their choices, rather than owning them.