The ratings for Nashville, ABC’s drama about the personal and professional tribulations of artists on all rungs of the career ladder in the titular city’s country music scene, aren’t exactly spectacular. T. Bone Burnett, the musician, songwriter, and record producer who is married to Nashville creator Callie Khouri, and who crafted the show’s signature gorgeous sound, left after the first season, explaining, “Some people were making a drama about real musicians’ lives, and some were making a soap opera, so there was that confusion. It was a knockdown, bloody, drag-out fight, every episode.”

There is some inherent conflict in trying to craft a successful network show, but Burnett’s not wrong, either. In the first half of this season alone, Nashville has thrown in several suspect subplots, including a fake pregnancy that ended in a fake marriage, complete with pig’s blood. A country starlet started an affair with a millionaire record-station owner, whose wife would like to make their situation even more complicated. And, in what seems like a positively mundane subplot by comparison, a daughter helped send her own father to jail.

And yet I can’t stop watching Nashville, and not because it features the kind of drama that makes me want to inhale an entire bag’s worth of popcorn. The show’s network-ordered soapy excesses, designed to lure in new viewers, are bringing them into what’s become a remarkably sophisticated exploration of how women are processed into the entertainment-industrial complex, and what happens to them when they try to carve out independent identities within it.

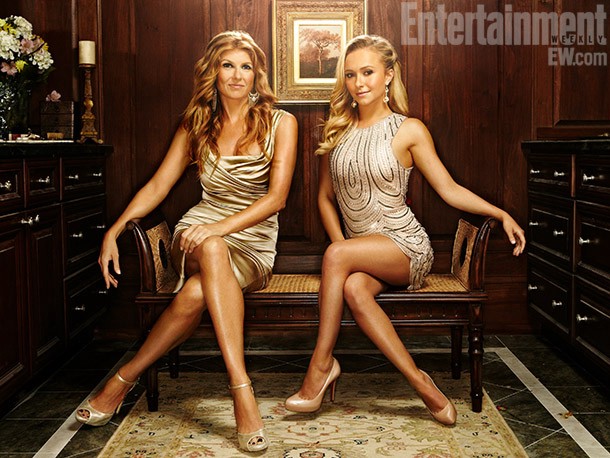

If we start at the bottom of the ladder, it’s striking to compare the trajectories of the show’s two ingenues. Scarlett O’Connor (Clare Bowen) began the first season of Nashville as a true naif, a waitress who loved country music, but never imagined that the poems she writes could be turned into lyrics — or that she could be the one to sing them. But Scarlett is both physically proximate to the music industry by virtue of her job, and she has a powerful connection in the form of her uncle, Deacon Claybourne (Charles Esten). And whether she recognizes it or not, her abilities with words, and her exceptionally pure, clear voice, are tremendously valuable commodities. Scarlett’s quickly signed to a songwriting contract, and then as a solo artist by Rayna James (the marvelous Connie Britton).

Rayna is an artist at the height of her powers and commercial viability, who’s trying to establish an independent label. But as well intentioned as Rayna, who’s in the midst of a creative revitalization herself, is when it comes to Scarlett’s career, she ignores that her protege is neither psychologically nor technically prepared for her career to move forward so quickly. When Scarlett is first delivered to the parent record company that owns Rayna’s label, she has an experience similar to Little Women’s Meg March at her first fancy party: “they powdered and squeezed and frizzled, and made me look like a fashion-plate.” Scarlett’s shocked by the way her identity is casually cast aside by the people who are making her over, flails at a rope line, and freaks out at her first appearance opening for a superstar named Luke Wheeler (Will Chase).

Unnaturalness doesn’t come naturally to everyone. And Scarlett’s experience is an often heartbreaking illustration of the very real costs of success. Even after she scrapes herself off the stage and manages to recover from a booing at her first Luke Wheeler show, Nashville finds Scarlett on the phone telling her mother that she isn’t cut out for the fame that’s been thrust upon her, but that she feels obligated to live up to Rayna’s hopes and her label’s investment in her.

Contrast Scarlett’s experience with Layla Grant’s (Aubrey Peeples). As the winner of a major televised singing competition, Layla’s effectively been through a boot camp that polished her hair, clothes and makeup, prepared her to talk to the press, and equipped her with a roster of iTunes-friendly cover versions of a popular song to give her an immediate connection with her audience. Grant’s completely at ease with the seemingly simple tasks that cause Scarlett the most trouble, but that doesn’t mean that she’s no longer at risk of show biz chewing her up and spitting her out.

Jeff Fordham (Oliver Hudson), the bottom line-conscious executive hired to run Edgehill Records (the label that’s at the heart of the show) signed Layla in part to reign in Juliette Barnes (Hayden Panettiere), a former teeny-bopper favorite who now looks at Rayna’s artistic integrity with covetous eyes. The two young women quickly fall for Fordham’s machinations. Barnes interprets every gesture from Grant as a threat, and tries to nuke her perceived rival at every turn instead of co-opting her or redirecting her artistic ambitions. And Grant can’t resist yanking Barnes’ tail, giving herself an encore while opening for Barnes, and thus cutting into Barnes’ set.

On a personal level, Grant, who’s in her late teens when she rises to prominence, lets Fordham set her up in a press-friendly fake romance with her labelmate and fellow opener on Juliette’s tour, Will Lexington (Chris Carmack). Will is gay — or at least bisexual — and deeply closeted, and views the arrangement with Layla as convenient cover. But Layla, who is in the dark about Will’s sexuality, can’t help but fall for the facade they’re putting on for the public. Watching her begin to care about Will is a strikingly sad, even cruel sight. It’s just as bad to mistake a facade for your real self as to recoil from the face that other people are trying to paint on you.

Juliette Barnes stands several professional levels above Scarlett and Layla in Nashville’s hierarchy, and she’s a year deeper into her negotiation with her brand. Barnes’ story arcs are often where some of Nashville’s soapiest segments take place. In the first season, her mother, a serious drug addict, killed herself after murdering her former sober companion, who had tried to blackmail Juliette after the two became lovers. This year, she started schtupping a married record-station mogul whose wife would badly like to get in on the action.

But when she isn’t the subject of scandalous storylines, Juliette is often in the midst of a battle to the death with her record industry for her independence as an artist — and for her psychic survival. As unstrategic and flailing as her efforts often seem, they constitute a kind of primal scream against Jeff Fordham’s attempts to manipulate her and the tyranny of teenbopper taste and required profit margins.

Negotiation is rarely Juliette’s tactic of choice. In the first season of Nashville, and in the midst of an enormous tour, Juliette began switching up her act, placing extra stress on her band and giving Edgehill’s previous chief fits when she started experimenting with acoustic sets and playing songs that weren’t even available as iTunes downloads, much less tied to a larger record that Edgehill could sell. This year, out on a solo tour, Juliette has accepted Layla, who she despises as a pale imitator, and Will, as her opening acts. But Juliette’s done everything she can to avoid being pushed out in favor of a girl just a few years younger than her, whether she’s punishing Layla for taking an encore, or co-opting a planned duet between Will and Layla so Layla can’t be the original artist associated with a promising new single.

It’s a profoundly unsisterly set of acts, playing straight into the competition set up by Jeff Fordham. But what choice does Juliette have? Should she submit quietly to the idea that her career should only be a few years long? If the entertainment industry is forcing women into competition with each other, is the most feminist thing to do to surrender?

In another area, Juliette acts with the broader interests of women in country music in mind. Her radio-station mogul suitor, eager to prove that he takes Juliette seriously as an artist and that he values her more than his business, fires a DJ who has the power to make or break a new female singer with his endorsement, and who has used his stature to sexually harass Juliette and other young women in her position. Juliette is initially furious at her boyfriend’s white knight-like intervention — she’d told the DJ to take his hands off her himself. But she ultimately decides to use the situation to her advantage, having the DJ rehired and summoning him for an audience where she delivers an ultimatum: the next time he touches another girl and Juliette hears about it, he’s gone for real, and for good.

Using your married boyfriend’s business connections to exact revenge is not exactly a sustainable plan for social change. But it makes sense that an angry, isolated young woman who’s suffered both physical and psychological abuse during her time in the music industry would be impatient. The story was a powerful reminder of what it takes to make gatekeepers in the entertainment industry change their behavior, and how ephemeral that change can be. If Juliette and her suitor break up, if the radio station is sold, if the DJ decides he can risk Juliette’s wrath, this small victory can be quickly reversed.

Finally, there’s Rayna James herself. Rayna’s past the age where she’s a target of casual sexual harassment, and she’s sold too many records to be subject to quid pro quos. But that doesn’t mean that she has complete artistic independence. And her storyline this season has illustrated how difficult it can be for women to amass the financial capital that would purchase them the independence to make their own choices about their careers — or about anyone else’s.

At the end of last season, Rayna set up her own label and reached handshake agreements with Scarlett and Will to sign them as solo artists. But when she was sidelined by a car accident, Jeff Fordham offered them both record deals, and Will, tempted by the bigger money and more significant opportunities that Edgehill could offer him, walked. A start-up is a tempting idea, but it requires an enormous amount of personal focus to get off the ground, and Rayna, who’s been dealing with her physical recovery, the dissolution of her marriage, and the revelation that her oldest daughter was fathered by a different man than her ex-husband, simply doesn’t have the bandwidth to do it right.

The obstacles aren’t just psychological and timing, either. As part of her plan to break free from Fordham’s influence, Rayna planned to buy back the masters of her recordings from Edgehill, using a loan from her father to acquire assets that would guarantee her financial independence. But when her father was indicted and his assets frozen, Rayna couldn’t follow up on her plan. And Jeff used Rayna’s contract terms to justify seizing the master recordings of songs she’d planned for her new album. The law and the larger pool of money are on Jeff’s side. Rayna may be famous and wealthy compared to most of the country, but it’s established in Nashville’s pilot that her family is cash-poor. The capital it takes simply to buy back your own music, much less set up a label that can survive independent of a larger corporate umbrella, is daunting. Rayna’s ambitions are admirable, but she’s running up against a system that has had decades to perfect its self-preservation mechanisms.

The truth is, if Nashville told these stories straight, we might feel crushed under their weight. As a woman who writes a great deal about how women have been systematically excluded from producing creative work in the corporate entertainment system, how few women are in ownership and leadership positions in the industry, and how rarely women are the subjects of entertainment in meaningful, substantive ways, I can tell you, that story gets exhausting. Even if Burnett and other people involved in Nashville’s production are trying to keep the show from getting utterly ludicrous, those suds do make the story slide a little more easily. And every week, Nashville gives us gorgeous music from Rayna, Juliette and Scarlett. It’s a beautiful reminder of what they’re fighting for — the right to make stunning art, and to preserve their humanity while doing it.