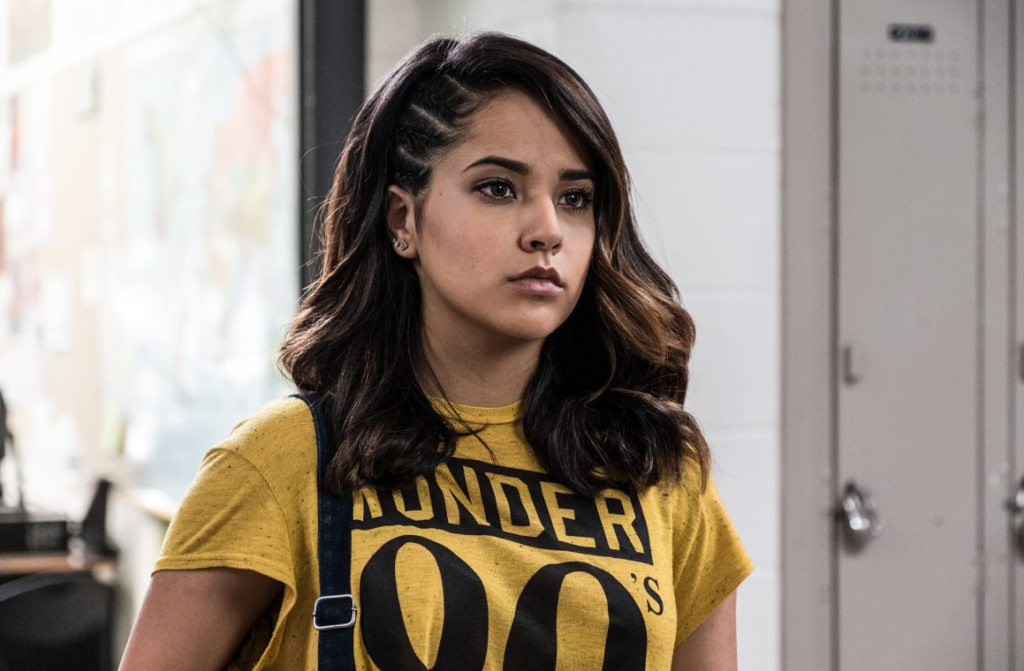

On September 29 at 10PM, when Virginia Johnson (Lizzy Caplan) walks briskly through the halls of a St. Louis hospital as she goes about her duties as the

assistant to Dr. William Masters (Michael Sheen), the sound of her clicking heels signals the arrival of Masters of Sex, created by Michelle

Ashford and with a pilot directed by Shakespeare in Love helmer John Madden, as the best new show of the television season.

And while Masters of Sex is refreshing because it’s part of a new crop of prestige cable dramas that focus on tough, intriguing young women,

including The Americans’ Soviet spy Elizabeth Jennings, Homeland’s Carrie Mathison, and The Bridge’s Sonya Cross instead of

middle-aged men with criminal careers, its specific setting and subject — sex research — make it something particularly special. Instead of giving us a

female character who mirrors men, Virginia Johnson’s very much a woman. And the choices she makes are a reminder that as easy as it is for men to waltz

past laws and standards of decent behavior and still keep an audience’s respect, real and fictional women alike face much higher standards.

The anti-hero characters who have dominated prestige television for the past decade and a half have been defined by their ability to violate all kinds of

societal norms while still remaining respected members of their communities. The drama — and the tension of these shows’ explorations of masculinity — comes

from their main characters’ abilities to continue passing in society no matter what terrible things they did to other people, as long as they met certain

expectations.

Tony Soprano became a breakout character in the first season of The Sopranos when he strangled a former mobster who had gone into witness

protection while simultaneously accompanying his daughter Meadow on a college tour. His ability to pull off both murder and parenting was a dizzying

display of multitasking competence that distracted viewers from the fact that Tony was a fundamentally bad man: our interest in how he pulled off the

balance distracted us from judging Tony as we might have treated a murderer who came across as less impressive. Similarly, Jimmy McNulty on The Wire could drink, chase women, and irritate his superior police officers and get away with it because his ability to come up brilliant

insights into unsolved crimes while being a personal mess was somehow an impressive display of masculine fortitude. It wasn’t until he started cheating on

his job, rather than the various women in his life, in the fifth season when he faked a serial killer to draw attention to crime in Baltimore that McNulty

lost some of our sympathy and ran his career in the ground. As long as a man manages to keep up the appearance of providing for his family, being good at

his job, or failing that, coming across as unflappable and tough, it turns out audiences are willing to forgive any manner of his sins.

Virginia Johnson has in common with these male anti-heroes is that she regularly crashes through the norms imposed on women. But what makes her different

isn’t just that she’s a woman, but that the rules Virginia has to break to live her life with integrity are ones that we’ve agreed are sexist and

retrograde, but that we still haven’t managed to decisively do away with. Masters of Sex’s entrance into the television landscape is a reminder

that fictional men can get away with murder, while fictional women — even ones who aren’t starring in period pieces — still get punished for enjoying sex and

prioritizing their careers over their families.

One of the delights of Masters of Sex is watching a woman who’s lived a somewhat aimless life come alive when she finds her purpose, when working

for Dr. William Masters (Michael Sheen) turns out to be an opportunity to do more than secretarial work. But the show is also a testament to the enormous

persistence it took for Virginia to pursue a career at all. When she rushes to enroll in classes at Washington University, something she’d told Dr. Masters

she’d already done, Virginia tries to find a program she can sign up for. “I want a degree in an interesting subject. Something important,” she tells the

registrar. “When I was your age, I thought my children were important,” the woman clucks at her. In another episode, Virginia’s housekeeper, irritated at

being asked to stay late to watch Virginia’s children when Virginia is caught at the office, tells her employer “You know what I do for my children? I

shift my schedule to be with them.” Later, she gives notice, because as Virginia puts it “Something about me being an unfit mother.”

Masters of Sex

is honest about the fact that Virginia does miss out on experiences she would have liked to share with her children, like reading the final installment of Race to Space with her son, who, impatient, tears through it with his new babysitter. But the show is a deft exploration of the difference between

Virginia’s regrets, and the critics who suggest that the only acceptable thing for her to do is stay home full-time, even if that would lead her family

without an income or Virginia without an easy way to make friends in St. Louis, given that she’s not a churchgoer. And what’s anxiety-inducing about Masters of Sex isn’t that we’re forgiving of Virginia’s bad mothering, but rather, how unforgiving society can be to mothers — and mothers can be

to themselves — who face the same choices today even if they are just fictional TV characters.

What distinguishes Virginia from a career-oriented character like Mad Men’s Peggy Olson, is that while Peggy still craves the mainstream

respectability of a marriage, and potentially children once she’s secured a husband, Virginia enters Masters of Sex having already abandoned any

number of the norms Peggy hopes to abide by. Virginia is a single mother, having divorced two husbands while Peggy’s surprise pregnancy was carefully

covered up by her alliance with Don Draper, and she gave up her baby for adoption. The idea that she’d raise a child on her own was never even a

possibility, especially given Peggy’s mental state when she gave birth. And while Peggy’s relationships other than her affair with Pete Campbell generally

proceed under the perception that they might lead somewhere, Virginia’s daring enough to value sex for its own sake. Peggy Olson represents the challenges

faced by many women who were her contemporaries. Virginia is so far ahead of the norms of her era that she’s facing problems that other women won’t

experience en masse for decades.

An example of this is Virginia’s relationship with a young doctor, Ethan Haas (Nicholas D’Agosto). The joke of their courtship — and Masters of Sex

is a very funny show, and not simply in a dark way — is that while Virginia is pragmatic about sexual pleasure, something she sees as worthwhile and

desirable, Ethan is a romantic who falls hard for Virginia after their first sexual encounter. Their liaison leaves Ethan obsessed and confused, especially

after Virginia doesn’t reciprocate the strong emotions nor is interested in a relationship that, for Ethan will grow out of good sex.

“Friends don’t fuck, Virginia. Lovers do. People in love with each other,” Ethan tells her at one point, bewildered and angry. “You’ll make love to me,

you’ll let me do anything, do everything to you.” For Ethan that must mean that Virginia loves him, because no woman’s ever been so sexually relaxed with

him before. “That’s like, the kind of sex you have when you’re married. Or on your honeymoon. I’m guessing,” Haas tells Masters after his first night with

Virginia. “Or like sex with a prostitute,” not seeing the contradiction he’s posing. But while Ethan may be acting like he is stuck in a past generation,

the explanation Virginia gives Ethan for why she had such adventurous sex with him is one that is very contemporary and he simply can’t process — “Because

I like it.” Ethan calls her a whore, but still keeps pursuing Virginia.

Masters of Sex

never suggests that Virginia is wrong to seek sexual gratification — by contrast, it suggests she’s sexually healthy and more centered than her boss, who

makes love to his wife in a dress shirt buttoned all the way up. But if she makes a mistake in her relationship with Ethan, it’s in assuming that just

because he’s a man he is capable of maintaining a friendship that involves sex. In the decades between Virginia’s arrival in St. Louis and the moment in

which we watch her adventures now, many men become more conditioned to meet Virginia’s ideal, capable of seeing sex as enjoyable even outside of a

relationship. But fewer women adopt Virginia’s attitudes. And however they approach sex, it doesn’t keep men like Ethan from calling them whores, or men

like Masters from treating men like Ethan with genial tolerance and women like Virginia as if they’re careless and unprofessional.

As prestige dramas have included female leads, they’ve often made them distinct by giving them problems. Carrie Mathison has bipolar disorder. Sonya Cross

is on the autism spectrum. Elizabeth Jennings is the survivor of a sexual assault that’s left her emotionally shut off from her husband. Men may be allowed

to misbehave, but it seems that women need some biological or psychological excuse for being dislikable. Virginia Johnson flips the script on that dynamic.

She doesn’t like sex and want to work because she was bonked on the head, but because those are actually her desires, and having flouted enough norms in

her life already, she’s determined to go after what she wants. And people are uncomfortable with her behavior not because they’re right to disapprove of

her, as they would be to react negatively to murder or mendacity, but because the way Virginia lives her life challenges norms that give men power but

leaves them unfulfilled in other ways. It turns out that feminism is a pretty powerful story driver, and one that doesn’t require all the characters in Masters of Sex to be degraded to be interesting. Other networks might be wise to take note.

The world of Masters of Sex is different from the one we live in today: more women can work, fertility treatments are more sophisticated, and

we’ve all benefited from what Masters and Johnson discovered about how the human body behaves during sex. But the show, especially if we consider it in the

context of other rich drama that networks like Showtime and HBO have aired in the last fifteen years, makes an important and unsettling point. If we’re

eager to see men like Tony Soprano, Jimmy McNulty, and Walter White break the rules, Masters of Sex is a reminder that, however much we might tell

ourselves otherwise, women are still stuck in the same thicket of contradictions that governed Virginia Johnson’s choices sixty years ago.